My dad’s four grandparents all came to Australia as youngsters in the 1840’s. Three were from the Eastern European area of Lower Silesia and the fourth was from Posen Province to the north. While this part of Europe was then part of Prussia, since WWII it has been part of Poland. As far as I am aware, I’m only the second descendent of those four Australian migrants from our branch of the Bahnisch family in Australia to visit the villages where they were born and spent their early lives. The only other person I know of who has done it is Noel Cameron-Baehnisch. He made this journey in 2004 at a time when it would have been much more difficult than it is now!

At the outset, I would like to acknowledge that much of the information that has allowed me to visit these small villages was generously supplied to me by Noel.

Until recently, discussion within our family had centred around the fact that ‘the Bahnisch’s came to Australia from Moettig in Lower Silesia, Prussia’. Nothing much was known in my immediate family about my father’s mother and her parents. So my journey of discovery to visit all four of these villages has been sweet indeed. As you might expect, the first village I visited was Moettig. All of the German place names were replaced with Polish equivalents after WWII, and so Moettig became Motyczyn. So here we go!

1. Motyczyn – formerly Möttig, and home of the Bahnisch’s.

This is a very small village to the N-E of the city of Legnica and about a 1 hr drive west of Wroclaw. In Poland, all villages and towns are announced with a sign of the type shown below. In the right-background can be seen one of the three reasonably new houses in Motyczyn.

A minor road runs through Motyczyn, and the entrance to the south is through an area of (apparently natural) forest (see below). There are two side-roads that constitute the village. On one of these, with only a few houses, I saw small stacks of cut logs. Noel saw a similar scene in 2004, so maybe there is some ongoing income being derived from the forest.

A minor road runs through Motyczyn, and the entrance to the south is through an area of (apparently natural) forest (see below). There are two side-roads that constitute the village. On one of these, with only a few houses, I saw small stacks of cut logs. Noel saw a similar scene in 2004, so maybe there is some ongoing income being derived from the forest.  This is one of the other new houses in town – quite smart, but garden still to come!

This is one of the other new houses in town – quite smart, but garden still to come!  At the corner of the main side-street is a house with a (pink) sign that includes the word ‘Soltys’. Noel says that this means ‘Village Head’.

At the corner of the main side-street is a house with a (pink) sign that includes the word ‘Soltys’. Noel says that this means ‘Village Head’.  Opposite is the house with the best garden that I noticed in the village.

Opposite is the house with the best garden that I noticed in the village.

But apart from a few well presented houses at the far end of the main street (just before it became a track through a wheat field), my overall impression of the village was unfortunately one of despair. Around one-quarter of the houses were no longer inhabited, and were in varying stages of dis-repair/decay.

It’s interesting to think that this large, now derelict and dis-used barn may have had something to do with the Moettig Bahnisch’s!

This is the view of the main side-street from near the far end, looking back towards the road.

This is the view of the main side-street from near the far end, looking back towards the road.  When I arrived back at the ‘main road’ corner, a couple of guys were fixing the front wheel bearings on their old tractor. The younger chap (sitting) spoke quite good English. He said that they have lived here for 12 years and that they have a farm of 12 acres. When I spoke to him about my distant local family connection, unfortunately, he didn’t seem very interested.

When I arrived back at the ‘main road’ corner, a couple of guys were fixing the front wheel bearings on their old tractor. The younger chap (sitting) spoke quite good English. He said that they have lived here for 12 years and that they have a farm of 12 acres. When I spoke to him about my distant local family connection, unfortunately, he didn’t seem very interested.  On the corner of the through-road stood a decorated cross – apparently as an after-math of local Catholic community activities during Lent.

On the corner of the through-road stood a decorated cross – apparently as an after-math of local Catholic community activities during Lent.  As I drove out of town, I observed that even the local crops didn’t seem to be yielding as well as many others I had seen in my travels! But the large woodlot (in the background) seems to be doing well.

As I drove out of town, I observed that even the local crops didn’t seem to be yielding as well as many others I had seen in my travels! But the large woodlot (in the background) seems to be doing well.

2. Dabrowka Wielkopolska, formerly Gross Dammer and home of Franziska Ruciak

Franziska was a Polish lady who married Willi Bahnisch in South Australia. It took me nearly 4 hr to drive the back-roads directly N-E of Wroclaw to reach Franziska’s home town. Dabrowka Wielkopolska is about a 1 hr drive due west of Poznan. I was pleasantly surprised to find quite a large and well-presented town.

While there are at least three roads that lead into the town, this one is interesting. While I was unsure of the meaning of the black silhouette sign in the background, Noel advises that it means ‘Place of Historical Significance’. I noticed these signs often as I approached small villages in the rural areas of Poland. But significantly, I think, there was no such sign on the outskirts of Motyczyn!

As well, behind this sign, you can see an area of wheat. This crop has been planted on several vacant lots witin the town – there are houses all around it!  Often, villages in areas like this in Poland are only a few kilometres apart. As well, they are sometimes connected with walking/bicycle paths as well as roads. At the end of this path, I found a cemetery. I scanned it for the family name Ruciak, but found none. I did, however, find two Franziska’s!

Often, villages in areas like this in Poland are only a few kilometres apart. As well, they are sometimes connected with walking/bicycle paths as well as roads. At the end of this path, I found a cemetery. I scanned it for the family name Ruciak, but found none. I did, however, find two Franziska’s!  This was by far the largest of all of the villages/towns that I visited. While there were some older homes in the town, there were none in the severe state of dis-repair that I had seen in Motyczyn.

This was by far the largest of all of the villages/towns that I visited. While there were some older homes in the town, there were none in the severe state of dis-repair that I had seen in Motyczyn.  And there was a rather wonderful lake in the centre of town.

And there was a rather wonderful lake in the centre of town.  This was a rather stately home, quite close to the centre of town. It seemed to be a private residence, despite the cross on the roof.

This was a rather stately home, quite close to the centre of town. It seemed to be a private residence, despite the cross on the roof.  While there was little commerce to speak of in the town (apart from a couple of small convenience stores), there was an (apparently) new Catholic church with a very modern design. Again, Noel advises that, while this church appears to be new, it is in fact old, but has had recent additions in the ‘folkloric’ style.

While there was little commerce to speak of in the town (apart from a couple of small convenience stores), there was an (apparently) new Catholic church with a very modern design. Again, Noel advises that, while this church appears to be new, it is in fact old, but has had recent additions in the ‘folkloric’ style.  Set behind it was a large old building, clearly with religious significance.

Set behind it was a large old building, clearly with religious significance.  It was locked and didn’t seem to be in use. But, based on its (former) grandeur, it had certainly been a significant building in the community in the past!

It was locked and didn’t seem to be in use. But, based on its (former) grandeur, it had certainly been a significant building in the community in the past! This was the only village in which I didn’t see a cross on a major street corner. Maybe this cross next to the catholic church served the purpose?

This was the only village in which I didn’t see a cross on a major street corner. Maybe this cross next to the catholic church served the purpose?  Another practice in Poland is to place signs at the end of towns leaving motorists (and cyclists and walkers) in no doubt that they are now ‘out of town’!

Another practice in Poland is to place signs at the end of towns leaving motorists (and cyclists and walkers) in no doubt that they are now ‘out of town’!  Being Polish, it would have been expected that the Ruciak’s worshipped as Catholics. But according to Noel, this family was a little different. Apparently, they worshipped as Protestants in the nearby tiny village of Chlastawa. As you can imagine, I was keen to see it. While it was 7 km away by road, in a direct line, the trip to worship for the family would have been a lot less.

Being Polish, it would have been expected that the Ruciak’s worshipped as Catholics. But according to Noel, this family was a little different. Apparently, they worshipped as Protestants in the nearby tiny village of Chlastawa. As you can imagine, I was keen to see it. While it was 7 km away by road, in a direct line, the trip to worship for the family would have been a lot less.

What I found right adjacent to this very small village was a total surprise. There was a massive Ikea distribution (and maybe manufacturing) centre! Along the building frontage, there were 23 semi-trailer loading bays. Nearby, there was a large truck park with dozens of trucks, presumably waiting to be loaded. And there were staff car-parks with hundreds of cars at each end of this massive building.

What I found right adjacent to this very small village was a total surprise. There was a massive Ikea distribution (and maybe manufacturing) centre! Along the building frontage, there were 23 semi-trailer loading bays. Nearby, there was a large truck park with dozens of trucks, presumably waiting to be loaded. And there were staff car-parks with hundreds of cars at each end of this massive building.

What an immense change to the local community/economy this business must have made.

But I was looking for any evidence that there had been a protestant place of worship here in the past. What I found was this Catholic church of wooden construction. And as with all of the other churches I had visited during my travels in Poland, it was locked. When Noel visited Chlastawa in 2004, he was with a Polish guide and was able to gain access to this church. He says that it was originally a Protestant church and dates from before the mid-1800’s. So it is likely to have been the place of worship of the Ruciak family before they migrated to Australia.

3. Pawlowice Wielke, formerly Pohlwitz bei Liegnitz and birth place of Wilhelm August Gregor, father of Louise Gregor, my father’s mother.

Pawlowice Wielke is south of Motyczyn, and only a short drive south-east of Legnica.

This village was a little different from many that I saw in that it had mostly cobbled streets.

This village was a little different from many that I saw in that it had mostly cobbled streets.  There were two very large buildings in the town, one of which had recently had a new roof installed. The second of these buildings was currently having its roof replaced.

There were two very large buildings in the town, one of which had recently had a new roof installed. The second of these buildings was currently having its roof replaced.  For me, the village had a very pleasant atmosphere about it, and it was a satisfying feeling to know that this was where my great grandfather, whom I had previously known nothing about, spent his younger days!

For me, the village had a very pleasant atmosphere about it, and it was a satisfying feeling to know that this was where my great grandfather, whom I had previously known nothing about, spent his younger days!  There were pleasant landscapes and extensive gardens.

There were pleasant landscapes and extensive gardens.  As well, crops in the nearby fields were flourishing.

As well, crops in the nearby fields were flourishing.  As I now expected, I found a decorated cross at one entrance to the village. There was also a stone-fruit orchard nearby with speakers strung in the trees and pleasant music playing. But no people! What was that all about, I wonder?

As I now expected, I found a decorated cross at one entrance to the village. There was also a stone-fruit orchard nearby with speakers strung in the trees and pleasant music playing. But no people! What was that all about, I wonder?  As well, there was a more permanent crypt at another entrance to the village.

As well, there was a more permanent crypt at another entrance to the village.

4. Bielany, formerly Weissenleipe, birth place of Ernestine Pauline Schulz, who married Wilhelm August Gregor and whose daughter, Louise was my father’s mother.

Bielany is a small village quite close to Pawlowice Wielke.

It is a village in two parts. At the bottom end of town by the main road, there are several businesses that you would not normally expect to find ‘in town’, including a scrap metal yard.

It is a village in two parts. At the bottom end of town by the main road, there are several businesses that you would not normally expect to find ‘in town’, including a scrap metal yard.  Again the main street of this small town was cobbled.

Again the main street of this small town was cobbled.  Towards the top end of town, it had an entirely different character …. a pleasant environment with well-tended homes and gardens.

Towards the top end of town, it had an entirely different character …. a pleasant environment with well-tended homes and gardens.

But there was very little still existing in this small town that might give a clue to the child-hood circumstances of my great grandmother.

But there was very little still existing in this small town that might give a clue to the child-hood circumstances of my great grandmother.

Again, at the intersection of the village street with the ‘main’ road was the ever-present cross.

I also attempted to visit the village of Karmin where Franziska Ruciak’s mother was born. I Googled for it and checked with my Navi system and both pointed to the same place, about 1 hr drive north of Wroclaw. So on the way back from Dabrowka Wielkopolska, I set the up the TomTom to go there. The drive across was mainly on very quiet and often one lane roads, with an average speed of about 60 km/hr. Lots of farming and lots of trees – both native and plantation. And it was raining! So this is some of what I saw:

Trees in foreground below are native – in the rear they’re plantation.

Trees in foreground below are native – in the rear they’re plantation.  This is actually a cobbled road!

This is actually a cobbled road!  Finally, I came to where my TomTom said that I had ‘arrived at my destination’! – see below. Not likely! You may be able to see a faint figure in the distance. I hadn’t yet noticed him when I took this photograph. But when I did, he turned out to be a burly, dishevelled looking woodsman. I must say I turned the car around and got out of there very quickly!

Finally, I came to where my TomTom said that I had ‘arrived at my destination’! – see below. Not likely! You may be able to see a faint figure in the distance. I hadn’t yet noticed him when I took this photograph. But when I did, he turned out to be a burly, dishevelled looking woodsman. I must say I turned the car around and got out of there very quickly!

When I returned to my B&B, I found that Noel was indeed correct – there is more than one Karmin in Poland. All I can confirm is that Fran’s mother wasn’t born about an hour’s drive north of Wroclaw!

It has been an emotional experience for me to have the opportunity to travel around these villages. A lot has happened here since the mid-1800’s, so I didn’t expect to see much evidence of the folks who left for Australia. But where are the old cemeteries of the communities who lived here then? Noel advises that most of them were deliberately destroyed after Poland took over in 1945. As well, across Europe, cemeteries are regularly reused by succeeding generations.

There was a lot of destruction in this area during WWII. Maybe that explains some lack of evidence of the past? And of course, there was the forced transmigration of most remaining Germans out of this area into East Germany after the end of WWII. As well, I’m told that Polish people were forced out of their homes to the East of here when part of what had been Poland was incorporated into what are now the independent states of Belarus and Ukraine.

I’m pleased that the folks who left for Australia made the decision to move. Their motivation to move was at least partly economic, seeking opportunity in a new land. It must have been a very difficult decision for them to make. They came to a land with a totally different natural environment and climate that would have seemed very strange to them for a long time! But I’m very pleased and grateful that they made the bold decision to turn their lives upside down for a new life ‘down-under’!

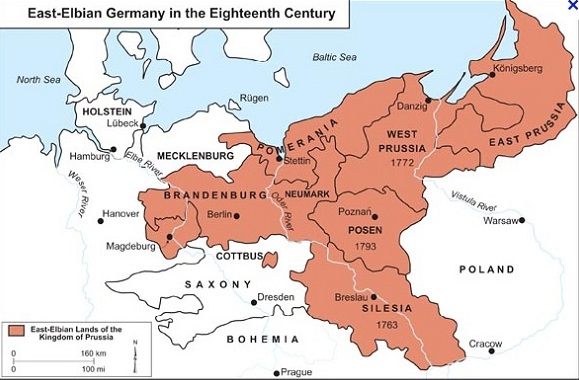

Update (Brian): This map shows the boundaries of Prussia in 1793, which on the eastern side are the same as they were in the mid-19th century:

Möttig, near the city of Liegnitz (now Legnica) is about 70 km west of Breslau (now Wroclaw). Dabrowka Wielkopolska, formerly Gross Dammer, is west of Poznań, pretty much on a direct line between Berlin and Warsaw.

Silesia was ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs under the Bohemian Crown until 1742, when Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia snatched it from Maria Theresa, a 25 year-old woman at the time. In 1740 she had become Queen of Bohemia and in 1745 became Holy Roman Empress Consort and Queen Consort of Germany in an arrangement where she shared the imperial role with her husband in a bandaid solution when the Habsburgs ran out of male heirs. She didn’t give up easily on Silesia, but conceded in 1763 after three wars.

Silesia was about 75% German, but Lower Silesia (western, lower down the Oder River) would have been close to 100%. After WW2 Silesia was assigned to Poland. Some 5-6 million Germans left Poland mostly from Silesia and the provinces along the Baltic (Pomerania, Gdansk (Danzig) East Prussia etc). In the 2011 census only 150,000 of 38 million Polish residents identified as German. Some 60,000 speak a language known as ‘Silesian’, a Slavic language influenced by German. I assume most of them live in Silesia, which now has a population of about 5 million.

Posen became Prussian in the second partition of Poland (by Russia, Austria and Prussia) in 1793. Prussia lost it when Napoleon reorganised the map in 1807 but regained it in 1815. Posen returned to Poland when it was reconstituted as a country after WW1. Silesia at that time remained with Germany.

Posen had about 35% German speakers, mainly in the towns and towards the west.

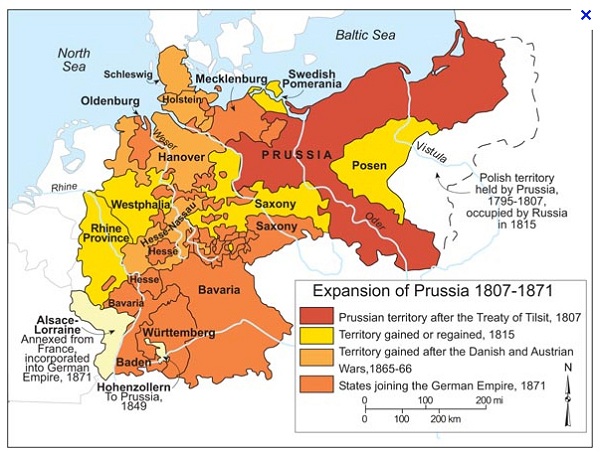

This map shows the changes in Prussia, leading to the reunification of Germany as an empire (there were four kings in that lot) in 1871:

Prussia when our ancestors left Prussia comprised the reddish-brown and yellow parts. Modern Germany is limited to the Oder-Niesse line.

Stupendous work, Len, I’ll comment in more detail tomorrow.

Wonderful.

Some additional factoids.

Silesia was ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs under the Bohemian Crown until 1742, when Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia snatched it off Maria Theresa, I think a 25 year-old woman at the time. She didn’t give up easily, but conceded in 1763 after three wars.

Silesia was about 75% German, but Lower Silesia (western) would have been close to 100%. After WW2 Silesia was assigned to Poland. Some 5-6 million Germans left Poland mostly from Silesia and the provinces along the Baltic (Pomerania, Gdansk (Danzig) East Prussia etc). In the 2011 census only 150,000 of 38 million identified as German. Some 60,000 speak a language known as ‘Silesian’, a Slavic language influenced by German. I assume most of them live in Silesia, which now has a population of about 5 million.

Posen became Prussian in the second partition of Poland (by Russia, Austria and Prussia) in 1793. Prussia lost it when Napoleon reorganised the map in 1806 but regained it in 1815. Posen returned to Poland when it was reconstituted as a country in after WW1. Silesia at that time remained with Germany.

Posen had about 35% German speakers, mainly in the towns and towards the west.

The church where Franciscka Ruciack (b. 1831) and her family worshipped in Chlatawa is highly likely to have been the wooden church photographed. Mark says that when Silesia was one of the lands of the Bohemian Crown, the Habsburgs banned Protestants from building stone churches. So during the Counter Reformation, Lutherans built in wood.

As far as I know Posen was never under Habsburg hegemony, but no doubt the practice applied there also. Probably the church was taken over by the Catholics when the Germans left after WW2.

With Len’s agreement, I’ve just added some historical/geographical context with a couple of maps at the end of the post.

Around the time your forebears migrated, Prussia was ascendant. Bismarck had an antipathy to the Pope. At that time Queensland was established as self-governing colony.

It is not clear how people move from Silesia, perhaps to Hamburg, and from there to go the US, then to Queensland. Was it related to the gold rushes (as in my wife’s family finding their way from Scotland to Victoria via California)? There was a greater density of steamship passage across the Atlantic, even after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The Atlantic passage was remained in use. That meant the antipodean colonies could provide incentives for primarily agrarian migrants, which was possible prior to the 1890’s depression.

My historical understanding of settlement patterns is very sketchy.

Len: My wife and I have 6 great grandparents between us who would have migrated to to Australia at about same time as yours did. (One of my wifes was an illegal boat person=(Swedish sailor who jumped ship). As far as I know all except the Swede would have sailed from the UK. One lot at least came by sailing ship.

It may have been the gold rush, a sense of adventure or lack of opportunity in Europe that drove them but I don’t have any information. The quality, speed and reliability of shipping increased dramatically during the 19th century.

wmbb, there were lots of reasons for leaving Europe by mid-century. Our great grandfather left from Hamburg in October 1848, aged 17. There were revolutions all over Europe in 1848. The King of Prussia survived, but at that time he was having a brawl with parliament over raising money to build railroads. By December he gave in and wrote a constitution which had a form of parliamentary democracy, while retaining his role as an absolute monarch. The key figure was the Minister President, appointed by the king, not parliament. Bismarck was appointed in 1862. There was a question as to whether Bismarck worked for the king or whether it was the other way around.

I don’t know much about it but a lot of Germans left in the 1860s and 70s at least some because they didn’t like Bismarck and his growing militarism, which led to four wars and the unification of Germany. Many came to Queensland at this time, more than ever went to SA.

Hamburg was a favourite departure point. They got there by boat down the Oder and then probably train from Frankfurt an der Oder (not to be confused with Frankfurt am Main.

Willi Bähnisch’s mum went with Willi and his sister to Hamburg and then simply disappeared. We don’t know whether she went back, or died from the plague, which was a bit rampant at the time, or died in transit.

I’ve done some writing on the conditions in Prussia in those times and might carve out a post.

Thanks a lot Len, that was terrific.

Some of my ancestors came from further to the north-east in Silesia. One lot were Prussian-Germans – who were with Friedrich der Grosse and stayed alive long enough to be rewarded with land in Silesia for doing so. The other lot were older-established Silesian-Germans: a mixture of German, Polish, Sorb (Wendisch) and with a stray Frenchman and a wandering Scot chucked in for good measure.

What struck me with your excellent photos were the differences in the style of buildings and in some of the vegetation only a relatively short distance (by Australian standards, at least) away from where my ancestors used to live.

All of the Germans in those parts were expelled or exterminated; the terrible stories of what happened are unwanted and unheard in the self-righteous English-speaking world. Hatred for atrocities and vengeance that happened 68 and 69 years ago does nobody any good. The Germans were replaced by the Poles who were kicked out of the western parts of Belorus and the Ukraine as part of Churchill’s treacherous deal with Stalin. Now those same towns and localities are increasingly prosperous, despite the Global Financial Fraud, and the younger generation have a bright future ahead of them.

Brian, one of the things often overlooked concerning Poznan (Posen) is that it is on the western side of Wielkapolska – Great Poland – and, as such, has great importance for Polish people. It would be interesting to look at the prehistory of the area: as corridor for southward migrating peoples and as a home of pre-Polish Slavic peoples perhaps? I don’t know – might be a ton of fun trying to find out.

Graham in my post on the origins of our language I said:

But German as such emerged from what is now southern Scandinavia and northern Germany about 500-0 BCE in the area covered by the Nordic Bronze Age. The Slavs came later, about 0 to 500 AD. From 6th century AD they spread south to the Danube, west to the Elbe and east to the Vistula rivers to occupy much of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Later from about the 12th century the Germans pushed back in a process known as ‘Ostsiedlung’, the eastward migration of Germanic peoples. That’s when they arrived in numbers in Silesia, also the western rim of Posen.

Things didn’t change much right into the modern era as shown on this map from 1929.

Hi, Cousin Lenny! You asked me from Prague (Czech Republic) to edit your travel diary and so here I am. By the way, thankyou for the postcard: written in the Rynek of Wroclaw City on the 24 June, it arrived here in Angaston, South Australia, on Friday the 4 July, the day after you returned to Brisbane (so it took 10 days to get here, which is about normal).

Our ancestors left Europe in the 1840’s (“1880’s” is a typo, which has misled some of the other commentators). The reason they left was a combination of demographic, economic, political and religious factors. The Baehnisches left in late 1848, which was the Year of Revolutions.

You were the second IN OUR BRANCH of the Baehnisch Family to visit Moettig, the ancestral village, but others IN OTHER BRANCHES have also visited.

The sign (a black silhouette of an old village) you saw and photographed and guessed means “urban area” in fact means “Place of Historical Significance”. You see these signs everywhere in Europe. We would say “heritage-listed”.

Ah, yes, the “lake” (actually the village pond) in the middle of Dabrowka!! I had forgotten about that. Brings back fond memories. By the way, if you go to GOOGLE MAPS, you can see the layout of these villages.

The church in the middle of Dabrowka is old but it looks “new”. The addition is new but is in the “folkloric” style. It is very well-maintained and is in use. The churches are locked for a good reason, whether in Poland or Australia. Wayside crosses and chapels are found everywhere in Catholic Europe.

The wooden church you saw at Chlastawa was indeed Protestant but is now Catholic. We had a Polish guide with us and so were able to look inside. Such wooden churches are quite common in Poland (and eastern Prussia and western Russia) which was a land of trees and few stone quarries. Remember Poland was flattened by a kilometre-thick sheet of ice during the last Ice Age.

The other village you visited was Bielany (misspelt “Beilany”) and it was formerly called Weissenleipe (“Weisseleipe” is my mistake). Here in South Australia, our power poles are called Stobie Poles (made of concrete and iron): in Poland you see all sorts of power poles, often looking like “tall tripods”.

The reason you didn’t find any Prussian/German cemeteries is because most of them were deliberately destroyed after Poland took over in 1945; it is also true of all Europe that old cemeteries are regularly reused again and again and again by succeeding generations over the centuries. It is not true to say that “all” the Germans were expelled from the eastern territories in 1945: most left of their own volition; some were expelled because they refused to be loyal to the New Poland; some remained and were intergrated into general Polish society.

Your trip to a Karmin produced lots of photos of Polish forests and I was vividly reminded of travelling through Germany which is full of forests just like these Polish ones. You were led to the former location of a hamlet called Karmin, north of Ostrow Wlkp, NE of Krotoszyn and SW of Pleszew. Or perhaps a former hamlet called Karmin some 40km N of Wroclaw City, some 5 km SW of Milicz. Our ancestral hamlet called Karmin was probably 10 km N of Pniewy, 20 km north of Brody (in other words, NE of Dabrowka). And there are other Karmins. Further research is needed.

Overall, it is clear that Poland has prospered during the ten years since I was there. It still uses the zloty rather than the euro (currency) but it is very much part of the European Union, right next-door to the economic powerhouse of Europe, New Germany.

Thanks, Lenny, for the photos. They have stirred up all sorts of emotional and nostalgic memories of my guided tour back in September 2004.

From your first-cousin’s son, Noel David Cameron-Baehnisch in freezing-cold Angaston, SA. Sat 5 July 2014. Pardon any typos, errors, etc.

G’day Noel, hope you don’t mind me butting in here. Surprised you mentioned Milicz (Militsch). You were right about the cemeteries; logic says that the dead generally stay dead and don’t bother anyone anymore – but at the end of the Second World War there was a lot of well-founded rage as well as completely illogical rage. Also, some of my relatives really didn’t have emigration included in their options. Blaming the younger generations for what their forebears did serves no worthwhile purpose at all – and the younger generations readily accept that what was once German is now Polish and nobody is going to take it off them so they are quite confident (in my opinion) in taking all that as a normal part of their own regional heritage and history and they get on well with young German visitors too..

Visiting that part of the world was, for me, a pleasant, surprising and enlightening experience – made more so by being able to struggle through a conversation in Polish (which is a lot easier for an English-speaking person to learn than the other way around).

There are a lot of things we can learn from modern-day Poland. ‘Rynek’; now there’s a word that should be adopted into Aussie English – short, exact and unmistakable. Railway timetables in different colours so nobody can make a mistake about which train goes where at what time. Our politicians can learn something useful as well from their robust democracy.

Brian, thanks for that link and map. I think there is likely to be a much deeper, more interesting and more complex story than the simple one of the Slavs bursting out of the Pripet Marshes one day and suddenly taking over much of eastern and south-eastern Europe; there are little hints of that deeper story here and there through the first millennium or so of general history.

Graham, certainly Anthony’s book gives only a summary outline of the emergence of the Slavs.

Noel, greetings and thankyou for your corrections and comments. I’m sure Len will make the necessary alterations in due course.

Folks, Noel is a legend in our branch of the family for his meticulous research into family history.

Thank you Len for posting this link, wow great to have this information & the photos. I’m Ken’s daughter and have caught the family tree bug. Did you go to any records offices while you were there, I know they could have been destroyed but on the show “Who do you think you are” some people have found records taken to in Brandenburg and in Poland as well as war records, I know there are things we probably don’t want to know, but there are still Stiller’s in Germany & surrounding countries. On the Stiller side we only have records of Johann Samuel Stiller & his wife, children & his in-laws. I’d like to know if he had siblings etc. and if some descendants of these families since live. I’m so glad you are discovering more on the Bahnisch’s good luck with people being able to tell you more. Lee Stiller

Hello Lee Stiller. Pardon me for being a stickybeak but from where exactly did the Stillers come originally?

Noel @ 11: Many thanks for your insightful and informative comments. I have made some alterations to the original post to take account of the corrections and additional information that you’ve provided.

It sounds like it was an emotional journey for you in 2004, as it was for me. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the benefit of a local guide. But I was surprised how well I was able to do with just a TomTom to guide me to the right places, some shoe-leather and a camera!

Lee @ 14: Greetings and thanks for your comments. I didn’t attempt to go to any records offices in Poland (or elsewhere). I had originally thought this would be a good idea, but was dissuaded from attempting it by a friend who has tried. Her experience was that the language barriers (and sometimes, the attitudes of the officials involved) make it impossible to do anything useful ‘on the ground’ unless you have the language skills (eg, German, Polish), and have some direct knowledge of the local archival systems. However, I understand that there are local groups who are willing to conduct family research on a contract basis.

But good luck with your family history research, wherever it may lead you! I have a number of friends who have caught the bug and it has become a very consuming, and I think rewarding passion for them!

GB @ 15, Pastor August Klavel led the first group of Lutheran refugees to South Australia from the village of Klemzig in the eastern part of Brandenburg, arriving in Adelaide on 21 November 1838.

From memory I think the Stillers came from thereabouts. In other words, the Neumark area east of the Oder. I’ll try to find out.

Hi, Brian!

Pastor Kavel (not “Klavel”) served at Klemzig (now Klepsk), which was indeed in Brandenburg Province but just a few kilometres from the point where the Provinces of Posen, Silesia and Brandenburg used to meet. Klemzig is just south-west of Dabrowka (Gross Dammer in Posen Prov.) and also features a wooden church, which I visited with David Zweck.

The Stillers came from “New Prussia”, far to the SW of Klemzig. They came from the hamlet of Nissmenau (today Wlostow, pronounced “v-WORSS-tooff”), a few km SW of the town of Naumburg (today Nowogrod Bobrzanski), on the Bober River (bobr in Polish, beaver in English, Bober in German, the River of Beavers). Just go to GOOGLE MAPS and type in Nowogrod Bobrzanski and then follow Highway 27 to the SW about 10 km to the obscure locality of Wlostow.

Prior to 1815, Nissmenau was in the Kingdom of Saxony but Prussia grabbed it at the end of the Napoleonic Wars because Saxony had backed Napoleon. It was briefly called “New Prussia” and then simply became part of Lower Silesia (Niederschlesien). So the Stillers had been Saxon subjects and then became Prussian subjects.

The Stillers and Schrapels (Johann Samuel Stiller was married to a Schrapel) came out on the “George Washington” in 1844, along with a large number of Polish families from Gross Dammer (which the Polish Ruciaks left shortly after). Johann Traugott Stiller-Schrapel was born on the voyage to Australia and he married Bertha Kaesler, niece of Ernst Wilhelm Baehnisch senior.

From Noel in Angaston SA. Pardon any typos, errors, etc.

Thanks Noel for the information of there Nissmenau is situated and the name the area is known as today. Yes the language barrier is frustrating. Samuel Stiller worked in this area, married & had two children there before coming to Australia. Trauggott was born on the ship, would be interesting to know where his birth certificate says he was born. Lee

Noel, Lee thankyou for that information about the origin of the Stillers. The relationship between Saxony and Prussia is interesting. Frederick the Great who ruled fro1740 to 1790 saw Brandenburg, Magdeburg, Halberstadt and Silesia as the core areas of the Prussian state. Nevertheless he consistently sought Saxony, I think for strategic reasons. During the Seven Years War he invaded Saxony and used their resources and manpower to fight the great powers who were lined up against him.

Napoleon exploited the antipathy between the two and used the Saxons against the Prussians. Prussia succeeded in grabbing half of Saxony after the Napoleonic wars.

Going further back, the first series of Holy Roman Emperors were Saxons. Up until the 18th century you would have bet on Saxony rather than Brandenburg-Prussia becoming dominant power in Northern Germany. The game changer came with the Prussian annexation of Silesia in 1742. Augustus III of Poland was King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1734 as well as Elector of Saxony in the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick feared that he would grab Silesia to make his lands contiguous, so got in first.

It seems to me that Nissmenau was close to where Silesia, Saxony and Brandenburg joined up.

Len, I have enjoyed reading your discovery journey in Lower Silesia and also the comments and further contributions by Brian & Noel.

In thinking about undertaking a simular trip to Silesia having someone with who knew the language well would be a benefit. such a trip would be of direct interest to my wife also as her family also originated from Silesia and also emigrated to Australia on the George Washington arriving in 1844 along with the Stillers, Schrapels & other families.

I only made the trip to the Barossa Valley, South Australia for the first time in January 2013 to see where the family first settled and where some still reside.

In the Lutheran Church museum in Lobethal I saw a large naturalisation certificate from 1847 That within their number were Samuel Stiller and his father-in-law.

Dale, always good to hear from you!

I enjoyed your linked post. I understand that my father was essentially fostered by the Stillers of Bethany (old Bertha Stiller was my grandfather’s cousin) from about age 4, when his father’s second wife had her first child.

Also my grandmother Louise Gregor was fostered by the Stillers and worked there as a servant.

Late tomorrow I intend publishing a post Noel’s nostalgic trip down memory lane. Noel Cameron-Baehnisch took a trip to Poland in 2004 with Homeland Tours, led by David Zweck and a Polish guide. Noel might be able to tell you whether David Zweck is still operating. I think Homeland Tours are. At the very least you’ll need some guidance on the pronunciation of Polish place names which is not at all straight forward. Noel knows how to do it.

Email me if you want to follow it up.

Brian: Have to disagree with you about pronunciation of Polish placenames: they’re different but not difficult at all.

Now, if you break up long words into syllables (you’ll get the feel for that pretty easily), most multisyllable words have the stress on the second-last syllable; it’s often the rhythm of pronunciation that trips up English speakers.

Most of the letters are pronounced roughly as we say them, except for:

the second A, with a cedilla under it =ong; the second E with a cedilla under it = eng; the second O with an accent over it =oo.

CZ and CI and C with an accent are the same =ch;

SZ and SI and S with a S with an accent over it =sh.

RZ and Z with an accent and Z with a dot over it =zh (like the French “j”).

By now all the Polish linguists will be jumping up and down with rage but just ignore them; they’re only after my blood. 🙂 Okay, you’re over all the hard stuff so the rest it easy;

J =y. CH =kh (sometimes H might sound like kh too). N with an accent mark =ny (maybe they picked that up off the Spanish swung dash).

The second L has a bar or oblique through it =w. C on its own usually =ts.

I think that’s it; if not, sorry I’ve overlooked something.

Don’t be intimidated by combinations you don’t find in English; they won’t bite: shch (szcz or s’c’); tzh (trz); pzh (prz); just practice saying them a few times and you’ll be right.

Good on you Graham, it’s still all double Dutch to me! I’d never get “dom-BROOF-kar” out of Dąbrówka, for example, which I’m told is how you say it.

The post Noel’s nostalgic trip down memory lane is now available.

Brian: It’s different but not too difficult. See, you’ve got that one pretty well right already. 🙂

Just a few more tips that might come in handy: Polish is highly inflected (like Latin, Russian, etc.) so if you stick to the core of a syllable and ignore the ending, in a placename that is, you can get some clues about how a place fits into its loca area. As in England, some placenames have “Greater” (WIELK~, abbreviated to WLK.) and “Lesser” (MAL/~); if you find NOW~ =”new” , look around for a nearby place with the prefix STAR~=”Old”. GOR~ =”Hill”, “Mount”. NA is a handy one =”By” or “On” a named stream. There are handy list of corresponding Polish and German placenames in several books and probably on the internet too ; -BORK =” -burg” is a dead giveaway.

Anyway, happy hunting.

Dale @ 21: Many thanks for your comments. While I have been to the Barossa Valley, I have never specifically sought out the places where my ancestors lived/worked, nor have I visited the known graves. Something to do in the not too distant future!

Re travel in Silesia, I met a guy when I was there who speaks six languages, including English, Polish and German. I spent some time with him, partly with a view to the possibility that other members of the Bahnisch clan may be interested in family history travel. This chap manages a place called Palac Krobielowice which has 26 rooms available for B&B type accommodation and is about 30 minutes drive west of Wroclaw. I’m sure this chap would be keen to facilitate any travel that you and your wife may wish to undertake – this may be another option for you. If you are interested, just let me know.

And Graham, even though you may find Polish easy, I found it a struggle. When you add all of the rules that you outlined together, it makes it pretty hard going to learn the language. But I must admit that I did become quite comfortable with the pronunciations of place names during the 6 days that I was there.

Wednesday evening. Checked the Internet and there is nothing concerning David Zweck’s tour business. I suggest someone check in the Lutheran Church’s “THE LUTHERAN” magazine: if he is not advertising it that official magazine, then his business is no longer operating. From Noel.

Len: Point taken. 🙂 I was lucky in that I acquired some conversational Polish when I was a kid – studying it is quite a different matter to acquiring it. Still, as you say, you did become comfortable with placename pronunciations in only 6 days; that’s the thing with acquisition, you don’t even know it is happening but it works; after 6 months you would have been speaking Polish well without even trying.

Thanks for mentioning that B&B (ex-palace or ex-manor perhaps?). I came across a few nice places that didn’t get a mention in guidebooks but were well known locally so I was directed to them; everyone I came across was quite polite and helpful. If I may offer a suggestion to anyone going over there: brush up your dancing. Dancing has almost disappeared here but almost everyone – old and young – went dancing when I was there; it’s a great social icebreaker.