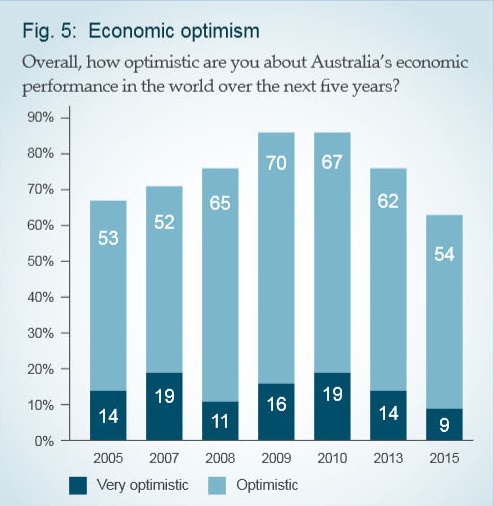

There is a vague feeling of unease abroad about Australia’s economic future, as the mining industry peaks, the car manufacturing industry evaporates and now Woolworths announces yet another job bloodletting – this time 1200 staff to go. This unease was picked up in the Lowy Institute Poll 2015, where our economic optimism rose from 2005 to 2009, then fell from 2010 to 2015:

Now the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) in a report Australia’s Future Workforce warns us that up to five million jobs are likely to be automated by 2030. David Tuffley, Lecturer in Applied Ethics and Socio-Technical Studies, School of ICT, at Griffith University, takes a look at the CEDA report.

- The researchers were looking at the probability of job losses due to computerisation and automation, and found that nearly 40% of Australian jobs that exist today that are at risk. They reported an even higher likelihood of job losses in parts of rural and regional Australia, with more than 60% at risk.

And:

- We know that jobs in agriculture, mining and manufacturing have been squeezed in recent years, but sectors that have been relatively immune to technological disruption, such as health, are also coming under pressure.

This industrial revolution is not unique to Australia, every developed economy faces the same tsunami. We tend to eschew throwing money at problems like this, yet we threw a few billion at small business in what Hockey has now branded as the ‘have a go’ budget. Nevertheless significant funding of appropriate education and innovation policy is necessary.

- In the CEDA report, Professor Martin is scathingly critical of Australia’s apparent lack of commitment to properly fund education and innovation policy. We are, he says, “woefully underfunded compared to global competitors”.

The federal government’s five Industry Growth Centres, announced last year, can and should be making major contributions to meeting the challenges. Yet, as Martin points out, their funding amounts to only A$190 million over four years.

The Brits with roughly tree times the population are providing over 15 times the funding. Ditto for other countries.

Tuffley says the CEDA report recommends the policy framework used by Denmark. Their approach has three aspects that Australia can learn from to good effect:

- Flexibility around hiring and firing

- Decent unemployment benefits

- Seriously good re-skilling programs.

We need to educate and re-educate people for the jobs of the future, and support rather than punish them through the transition.

In an earlier article Tuffley looked at the required thinking skills for the future. Handling large data sets will be part of it, but also communication skills and the ability to work in teams. He summarises in the present article:

- We have always needed people who can focus their attention on a problem and arrive at creative solutions, and who are not bound by orthodox thinking. And will continue to need them.

Creativity and innovation are not just cliches of the modern age. It is the kind of thinking that learns from history, but which is not bound by it. It sees the patterns of the past and projects them into the future to predict where the world will be in five or ten years.

This is the essence of the kind of thinking that drives innovation. Proactively looking ahead and positioning ourselves for when the future arrives, not waiting for it to arrive and being caught flat-footed.

I suspect that Bill Shorten’s notion of giving everyone computer programming skills draws on this kind of thinking. However, we need to define creative thinking more broadly. I liked Tuffley’s reference to Howard Gardner’s Five Minds for the Future. Although Gardner is focussing on leaders he introduces a concept of ethics and civic responsibility which should be universal.

Then of course we need modern infrastructure including public transport and communications, where the Abbott government vision is not even second-rate.

Straws in the wind

Here are a few straws in the wind that have passed by my consciousness recently.

A few months ago I underwent an operation to remove two failed titanium implants from my jaw. The cavities in the bone had to be repaired by a powder manufactured in Switzerland. As the orthodontist said “Pass me another phial” he explained that each phial costs $200. Then he stitched me up with thread also from Switzerland at $180 a piece.

Blood products company CSL, an Australian multinational, is building a new plant to manufacture synthetic versions of the body’s blood clotting agents. The 500 workers will be in Switzerland. The company says that if we had a 20% corporate tax rate instead of 30% they may have considered Australia. The Swiss rate is 18%. CSL’s CEO was arguing for a 10% concession for advanced manufacturing ventures. The OECD corporate tax rate average is now 25%.

Switzerland, apart from Norway, is the wealthiest decent-sized country in the world.

In my post on electricity futures in Queensland I mentioned that there had been difficulty in building the 3.25MW solar array at the Gatton Campus of the University of Queensland because of the lack of a skilled workforce. From memory Prof Foster said it cost them twice as much as it would have cost in Germany. Obviously in a solar future we are going to need TAFE courses for training solar installation technicians. I wouldn’t think, however, that they’d need computer programming skills.

On the whole, though, we need to make our own future, not just let it happen.

Brian: I think the problem is more complex than educating, reskilling and, and, and..

We have what we think will be game changing technology that will see automatic systems do a whole raft of things that are currently done by humans. There are a number of things that could happen:

Scenario 1: The capitalists show no signs of realizing that, if you are using robots to push down the wages of their customers and shrink the workforce your business has to shrink. Result: The economy tanks and the revolution starts. (Pushing the best educated out of the workforce increases the chance of a revolution.)

Scenario 2: Jobs for humans increase. Computerization of offices and engineering simply allowed us to investigate more options and manage more data. Problem: The robots can optimize without our help.

Scenario 3: The gains will be used to give people more free time and/or increase the income of all Australians. Will need major changes to the way the economy works at the moment. May need the end of free trading globalization.