Last Thursday Andrew Robb and 11 other trade ministers signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement, rejecting calls for an independent cost-benefit analysis after the World Bank estimated it could lift Australia’s economic output by just 0.7% by 2030.

You see, everyone knows that free trade is good for us, Labor agrees, it’s just the ignorant Greens, trade unions, green groups and lefty outfits like Getup that disagree.

Actually, as recorded in the AFR, the studies are all over the place.

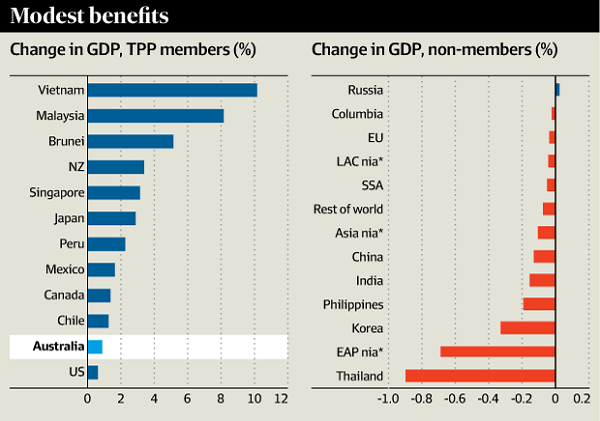

The Washington-based Peterson Institute emphasised that the US would be the biggest beneficiary of the agreement, and agreed with the World Bank about Australia. The Tufts study suggests Australia’s economy will expand by 0.87 percentage points by 2025, but the US and Japan will suffer negative growth. The World Bank has the US as barely growing at all. Here’s the World bank graphic:

You will notice that countries outside the agreement are expected to suffer.

It took eight years in the making, and Robb has now set his sights on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) a huge trade agreement in the Asia Pacific Region, including China and India, which he hopes will conclude by the end of the year. (Oh, wait, he’s retiring from politics!)

Signatories to the TPP now have two years to ratify the agreement in their parliaments. Generally speaking these agreements are worked out in secret. Governments then have to either accept or reject them as a whole. There is actually a significant chance that the US will not sign. On one recent count the TPP would pass the House of Representatives by only six votes. Of interest, Hillary Clinton is opposed, contra the Obama administration. Donald Trump says he would renege on the deal.

A quick look at opinion surveys seem to indicate that Pew Centre surveys favour trade deals more than the Wall Street Journal/NBC poll which found that 37% of adults polled thought trade deals helped, 31% thought they hurt, and presumably 32% didn’t know.

- But that is a turning point: it marks the first time in more than 15 years that a plurality of Americans said that free trade helped.

If I understand English correctly that statement is wrong, but you know what they mean.

Polling results seem to depend on where you are in the pecking order, what the economic conditions are like at the time, and very much on what question is put. PollingReport.com gives the results of many polls, showing American opinion significantly divided. An Essential poll on the China deal saw 41% of Australians saying “Don’t know enough to say” when that option was offered. Of the rest 38% were with the unions opposing the deal, while just 20% agreed with the government.

I have not read the 16,000 pages of the document, available here, so I’ll point to the concerns expressed by AFTINET, a national network of community organisations and individuals which campaigns for fair trade based on human rights, labour rights and environmental sustainability.

Top of the list foreign corporations could sue governments if their laws harm the companies’ investments. They are entitled to do this under Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), which are already common in other trade agreements, notably NAFTA, where, according to the Council for Canadians, Transcanada recently filed a US$15 billion NAFTA challenge after U.S. President Barack Obama’s rejected the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline.

These cases are not heard by courts, rather in private by specially convened panels of three, usually trade lawyers. There is no provision for appeal.

Philip Morris tobacco company sued the Australian government over its plain packaging laws under an old trade agreement with Hong Kong. Mercifully it failed, but the fact the TPP had to specifically exclude tobacco shows the potency of ISDS provisions.

AFTINET also expresses concern over higher medicine prices. The main concern is for reduced access to affordable medicines, especially in developing countries.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has called the TPP the “worst trade deal ever for access to medicines”.

A further concern is copyright monopolies on the internet:

- detailed specific rights for copyright holders could prevent governments from introducing future reforms to improve consumer rights or respond to technological change. Sydney University Professor Kimberlee Weatherall has described them as “unbalanced, outdated and inflexible.”

The TPP also contains threats to food labelling.

- The TPP seeks to standardise labelling requirements in the region, which could mean that countries are limited in their ability to control labelling for food and alcohol. This would restrict regulatory capacity even in light of new research.

Our government could be sued under the ISDS mechanism, for example, if we wanted labelling for genetically modified food.

Finally there is concern for the secrecy of the negotiations. In Australia Cabinet gets to approve the deal, parliament votes in the enabling legislation. The Senate Inquiry called it a blind agreement.

See also Patricia Ranald, AFTINET co-ordinator, in the SMH last September.

Elsewhere the Lowy Institute takes a look and The Conversation has a long list of articles by academics from various perspectives.

Malcolm Turnbull hailed the trade deal as central to Australia’s prosperity, Nick Xenephon thinks it’s a dud.

Ben Eltham in a detailed commentary last October asks whether the deal is worth signing so many of our rights away. Almost certainly not. Our economy is already very open.

- Even the hard-heads at the Productivity Commission think that bilateral and regional agreements like ChAFTA and the TPP deliver only incremental gains. “The increase in national income from preferential agreements is likely to be modest,” the Productivity Commission reported in 2010.

Yes, and the Productivity Commission said current processes for assessing and prioritising such deals lack transparency and tend to oversell the likely benefits, and should be properly assessed by an independent body.

Eltham also says this:

- But the US-Australia free trade deal has not delivered. Indeed, new analysis from the Australian National University’s Shiro Armstrong suggests it might even have made us worse off. “Australia and the United States reduced their trade with the rest of the world by US$53 billion and are worse off than they would have been without the agreement,” Armstrong wrote in August.

Peter Martin picked up many of these concerns last February, pointing out that The Lancet and the Australian Medical Journal editorialised against the agreement.

The US is strongly in favour of investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms. Martin says that Labor in government refused to have them in any of its trade agreements and believed it was on the verge of getting a carve out for Australia in the TPP because of its strong judicial system.

Professor David Collins, sitting in London, says the deal should bring phenomenal economic benefits to its 12 trading partner nations.

I hope those links will assist you in coming to terms with the TPP. Back in the early part of this century I followed trade closely and wrote a bit about it too. In 2004 I did a piece for Webdiary, Picking the low-hanging fruit first on the US Free Trade Agreement. John Quiggin called it “an impressive critique”. Any way I began the piece with this:

- The distinguished American scholar Immanuel Wallerstein sees multilateral trade negotiations as a means for the core economies of the world, North America, Europe and North Asia, to open the peripheral economies to trade and investment, while protecting their own. He sees this as part of the structure of capitalism and what he calls the World System. It is not a mere policy option, but rather an inherent structural feature.

Whether Wallerstein is ultimately right or not, he bases his remarks on a lifetime of study of the 500 years or so that capitalism has prevailed. We must expect, therefore, that the tendency of the strong to exploit the weak is very durable.

In the previous year I’d done a long piece on the World Trade Organisation meeting at Cancun Reaching for the Moon: how the poor lost and won at Cancun. That time I began with this:

- This is the story of how 15% of the world’s population in the rich countries ruthlessly exploits the remaining 85% while pretending that everything is done for the benefit of the exploited.

If one focuses on the truly powerful, the real movers and shakers, it is the story of a few thousand screwing the rest, while a considerable number of lackeys, including the elites in poor countries, are paid pretty well for their troubles. Seen this way, US and EU trade representatives Zoellick and Lamy are well-paid lackeys working for the large corporate interests.

Now the poor and the marginalised have put up their collective hand and said: “Stop right there. Let’s have another look at how this whole thing works.”

Since then developing countries have held out for a better deal, and from the World Bank graph above seem to be getting the best of it. Prior to 2003 the World Bank, the WTO and the IMF had mostly sung from the same song sheet – free trade will lift you out of poverty. In resisting this assault they had a great deal of help from the non government organisations. Oxfam compiled a large study Rigged Rules and Double Stantards: trade, globalisation and the fight against poverty.

Chapter Five is particularly instructive:

- IMF–World Bank staff arrived in developing countries, armed with complex studies apparently justifying their prescription of sweeping trade-liberalisation measures.

Most of the studies – and even more so the policy conclusions based on them – lacked credibility. The majority failed even the most simple test of causality: it was impossible to determine whether openness caused growth, or whether countries became more open as economic growth increased. Moreover, definitions of ‘openness’ were so wide-ranging as to be meaningless. Everything from exchange rates and macro-economic strategies, to import barriers and the size of government were included. One detailed review found that when import barriers were isolated as an indicator of openness, any meaningful relationship with growth evaporated (Rodriguez and Rodrik 1999). In other words, there was no relationship, positive or otherwise, between the policies advocated by the IMF–World Bank and the policy outcomes predicted. Yet import liberalisation was dogmatically pursued as an adjustment goal.

And:

- It is almost axiomatic that countries with growing trade/GDP ratios will have higher than average growth rates, since world trade is growing more rapidly than global GDP. However, association is not the same as causation: it could be that countries participate more in trade because they are growing more rapidly. The only conclusion that can be supported with any confidence is that countries tend to become more open as they become richer (Rodrik 2001a).

Back in 2004, Quiggin said trade agreements are really about economic integration. Peter Martin emphasised that more than trade was at stake.

With the possible exception of Vietnam, the countries entering into the TPP are developed or transitional economies, growing, opening and looking to trade more. In principle facilitating trade and openness is, for the most part, a public good. As Patricia Ranald of AFTINET pointed out, we already have trade treaties with 9 of the other 11. But it needs to be fair, and it needs to allow us democratic freedoms to protect our health and our environment, but beyond that to choose our own social and cultural arrangements.

Trade agreements will always reflect to some extent the wishes of powerful lobby groups, such as farmers with a vote, or, more likely large well-organised multinationals like the pharmaceutical industry. Peter Martin points out that there are 20 separate chapters, with mind-numbing detail. We take 22 negotiators to meetings, the US 80 and Japan 120. It would be a miracle if everyone was happy with everything at the end, but once the deal is struck, we’re stuck with it. For us, whether we gain much is moot, but there are definite deficits about which we should have concern.

I’m struggling to find a morally positive argument for Trade barriers. That is, more harm than good.

Correction; … more good than harm….

( I blame these 2am starts we’re doing at work )

The thing that strikes me is that, on one hand, the free trade fanatics claim that free trade encourages competition and the creativity it is claimed to encourage. On the other hand they do their best to stop countries experimenting with trade systems that disagree with their obsessions.

The GFC gave us a good demonstration of what happens when the world is too interlinked and countries are blocked from doing anything to avoid unsustainable growth in international debt.

What has happened since then is hardly a ringing endorsement of rampant free trade .

Countries need to be able to make decisions about their economy, the health of their people without systems like the TPP forcing them to make poor decisions.

How does the TPP force anybody to make poor decisions John ?

current “free trade agreements” create incentives for large companies to divert resources to trying to gain maximum benefits from the agreement – requiring more accountants, financial advisers and lawyers rather than encouraging product development and innovation.

Jumpy: The TPP is all about limiting government’s ability to make decisions that are in the country’s interest.

John, the same could be said of UN Treaties, Protocols and Conventions.

Douglas, they do the same now navigating around different taxing jurisdictions and artificial market distortions that Governments change every 5 minutes.

That’s easy, Jumpy.

Trade barriers are justified when your local industry is in danger of being wiped out by dumping, or heavily subsidised imports.

Also you’ll find that the ‘Asian tigers’ initially got a go on by doing everything the free market economists tell you not to. Picking winners, subsidies, developing industries behind tariffs and other trade barriers. Read Chapter 5 in the Oxfam report or my piece on “Reaching for the moon”.

Firstly, Australian industries are in danger of being wiped out or not even being born due to genuinely cheeper products from overseas. Think solar panels, would you like a %100 tariff on those from China to give our locals a chance ?

If a foreign Government wants to punish their people financially to make a product cheaper for Australians, good for us and bad for them.

As for the Asian Tiger temporary bubble that sees their standard of living still well below ours, their rise was started by opening up trade where there was none, their fall will be because of the things you mentioned.

Venezuela had a short burst of prosperity and happiness due to trade and price setting, look at em now.

( Bugger! I missed my chance to include ” Trump, Hugo Chávez and you it seems……….” )

Jumpy: You say:

It is not good for the Australian “us” whose jobs are being lost because of unfair competition.

I have this touching idea that trade should be about win/win. Unfortunately the free trade fanatics seem to have forgotten this.

Ok John, tell me how much a protectionist fanatic would add to solar panels ?

Or medicines ?

Foods ?

We must protect Australian jerbs, they’re taking our jerbs !.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rUTnNKhF-EU

So then, Douglas Hyde, are we heading into a Late Dark Ages- Early Middle Ages situation where we will be supporting herds and herds of unproductive latter-day monks, nuns, priests, bishops and the like worshipping all day long in their Temples of Mammon?

Oh, the joy of it all – now where can I get myself a dark grey Armani habit, a super-smart gen-15 psalter and an altar with a harbour/river view on the 99th floor? If you can’t beat them, join them.

OK Jumpy, go ask this mob, who claim to make the actual solar panel here in Oz.

This outfit assemble solar panels from imported components.

There may be others.

When you contradict me directly about Asian tigers and don’t appear to have read the linked material I’m not up for a conversation.

Venezuela is a unique case and I don’t think it can be used to prove anything about trade.

Chris Berg argues that anti-dumping action against canned Italian tomatoes is a conspiracy against consumers.

He doesn’t spare a thought for farmers who might be put out of business along the way.