Murphy’s law says that anything that can go wrong will. There is an awful lot that can go wrong with Australia’s economy in 2017, as this article by Michael Janda sent to me by John D shows.

Murphy’s law says that anything that can go wrong will. There is an awful lot that can go wrong with Australia’s economy in 2017, as this article by Michael Janda sent to me by John D shows.

An associated question is how should we react? Should we maintain our optimism, or should we take precautionary action? It’s a serious question, to which I’ll return later.

Here’s a summary of what could go wrong.

1: Car industry shutdown

Ford closed manufacturing last year nixing 600 jobs directly, but with estimates that as many as seven jobs were affected by every job lost directly.

Toyota and Holden closing could see another 40,000 jobs go.

Australia’s unemployment rate is at 5.7% (around a percentage point above the US), and the auto closures would push it above 6 per cent. A further 8.5% have less work than they would like. Combined, that is higher than it was in the 1991 recession.

2: Mining investment bust continues

BIS Shrapnel think Australia is only about halfway through the resources investment downturn.

I can report that Macquarie Equities think there will be an upturn in mining exploration and investment from the second half of the year.

Also Brendon Pearson thinks Stories of Australia’s mining decline were greatly exaggerated. He says that what comes after the mining boom is a much bigger mining industry. The official estimates for resources exports for 2016-17 have been revised upwards to $205 billion. That’s up by $40 billion since March, which is more than the annual total from tourism.

Employment in the sector is three times what it was a decade ago, not counting the hundreds of thousands of people who work in the mining equipment and technology services sector. Productivity in the minerals industry is growing faster than any other sector.

Oh yes, Pearson is chief executive of the Minerals Council of Australia.

3: Commodity price snap back

Commodity prices could snap back. It seems to depend on China, and perhaps Mr Trump.

4: Property price fall

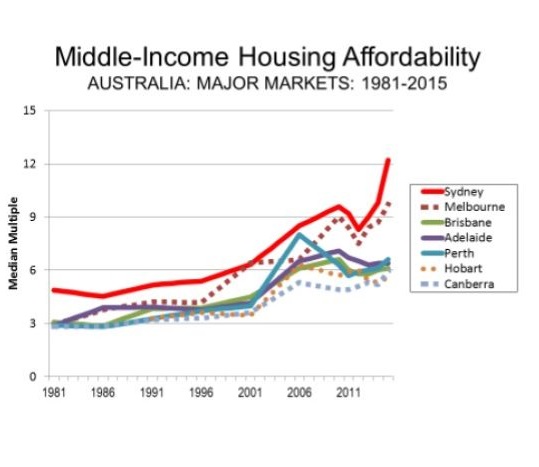

Property prices could fall. It looks as though they should in Sydney and Melbourne:

Janda says that if you think Australian property prices never fall, just ask someone in Perth or Darwin, or one of the regional towns or cities in a mining area.

5: Construction boom peaks

The construction industry alone accounts for about 10% of jobs. If the building boom rolls into bust 200,000 jobs could be lost.

6: AAA lost

Most think the triple A credit rating will go, come the May budget. The main effect:

- it could undermine international confidence in the Australian economic narrative, seeing money pour out of a country that relies heavily on foreign funding of its businesses, houses and large trade deficit.

And the cost of funds to banks would increase.

7: Australian banking crisis

If items 4-6 above happen it could precipitate a banking crisis. Australian banks rely 60% on home lending, and Janda says many who get loans shouldn’t.

Probably the big banks are too big to fail and the government would step in, but it would be messy.

8: China slowdown

We have to hope that the commissars who run the place know what they are doing. However, that doesn’t preclude them needing less resources.

9: The Trump factor

The markets have been factoring in Trump’s promise to crank up spending on infrastructure, and the American economy generally.

10: European disintegration

Both France and Germany have elections in 2017. If right-wing parties are successful in either the EU could fall apart.

Doomsday scenario

If all of the above happen at once, or a substantial number of them, we then have a doomsday scenario. Janda seems to think we will probably muddle through, but all of the identified risks are real and plausible.

What should we do?

Rationally, we should turn all investments into cash, but if we did we’d have to hope that everyone else would not follow suit. If everyone sold their bank shares, for example, the banks would go bust.

Things go better with us if we are less anxious, worry less, and see the world with a positive bias. However, our personal psychological orientation is unlikely to affect what happens in the economy, rather how we personally survive. What we do, faced with the above risk profile, depends very much on our circumstances. For most, there will be a risk that interest rates will go up, so minimise debt. Those depending on income from shares, including income derived from superannuation, could see their income diminished. Australia’s run of positive growth since 1991 could come to an end.

Meanwhile we are told, in an article by Ben Potter in the AFR, that Most Australian manufacturers lack competitive edge.

This is a salutary tale:

- When Chinese counterfeiters copied Codan’s metal detector five years ago and sales to Africa plunged, the Adelaide company tried to enforce its legal rights.

“We tried to stop them in the market by going out there and doing raids and so on, and it was just like playing whack-a-mole,” chief executive Donald McGurk said.

So Codan reinvented its metal detector and brought in engineers from its radiocommunications unit to encrypt the intellectual property. Sales and profits bounced back.

“The only way to stop them is to out-innovate and outsmart and out-compete them in the market,” Mr McGurk said.

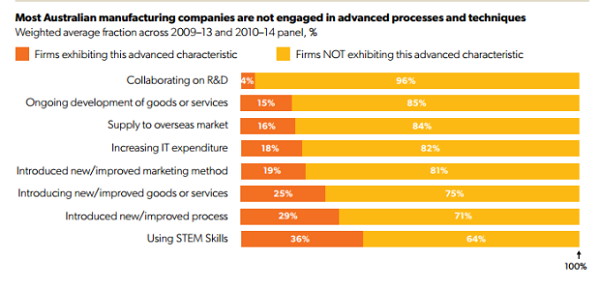

A report from the Turnbull government’s Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre finds that most Australian manufacturing firms do not have the chops to compete at this level.

- Australian firms do much less R&D than their counterparts in top manufacturing nations such as America, Japan and Germany, management is weak and manufacturing labour productivity is only 60-65 per cent of international benchmarks.

Still, the report says there is a prize for Australian manufacturers willing to put in the hard yards and move up the value chain – a potential 25-35 per cent increase in value for the $100 billion sector over the next decade.

Australian firms have one big advantage over their American and other foreign counterparts – skilled workers in medical devices and aerospace are 38-40 per cent cheaper to employ than their US counterparts.

No easy fixes, but with the right leadership and spirit there is no reason why a small nation of 24 million cannot make a good living in the modern world.

…and,..collapse of the A$ to 50 cents against the US$ is speculated.

Our real problem is that we (and much of the rest of the world) have allowed the fanatics from the WTO to drive us into positions where we have little control over what comes across our borders and what industries we want to support.

We need to think about the alternatives and how the world can set up something that gives more control to countries while encouraging countries to avoid both world destabilizing surpluses and country destabilizing deficits.

I tend to favour systems based on import licences rather than fiddling with tariffs.

John, I’ve just come across a long review article in the London Review of Books of How Will Capitalism End? by Wolfgang Streeck. He asserts that the nation state should take primacy. I guess he means that companies should not operate transnationally.

It might work for larger countries like Germany, but I couldn’t see it operating for Slovakia, Denmark, or other small countries.

Nevertheless, if you have the time, he has much of interest to say.

Brian: A problem with the EU and even more so the Eurozone is that it combined some economic and trade stuff but didn’t combine major expenses like welfare. It may have been better if it had been more like Australia instead of a federation of states on testosterone.