No doubt about it, Guy Rundle told Phillip Adams.

However, that is a bit different from saying that there was direct CIA involvement.

In his Crikey account Rundle points out that in Kerr’s correspondence with the Palace he refers to the refusal of supply as a “deferral”, because supply until the end of November existed. There was no urgency to sack so early, except, as we shall see, supply was not the only story being played out.

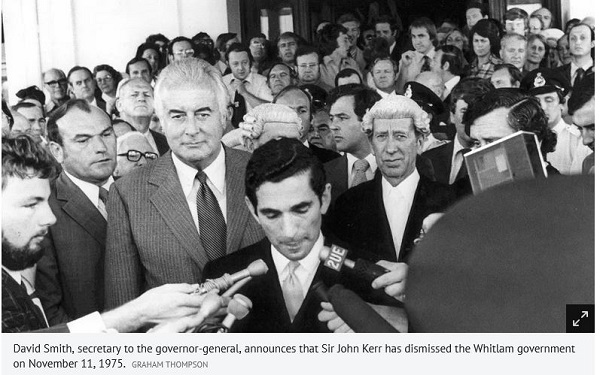

Immediately after the sacking, as expected:

- on November 11, … the House immediately passed a no confidence vote in Malcolm Fraser and a confidence vote in the “member for Werriwa”.

How did Kerr deal with that? He told the Palace on November 20 that he presumed the reserve powers to carry over beyond the crisis, and to give him the authority to prorogue parliament until the election, refusing any communication from the House of Reps speaker, with Fraser’s commission as caretaker PM in tact.

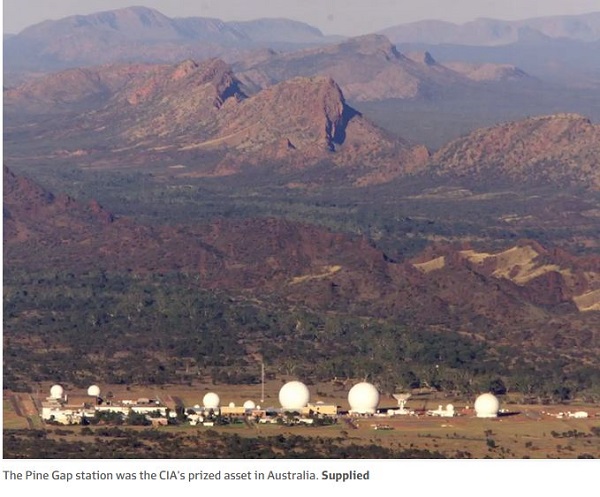

One of the duties that befell Fraser was the renewal of the Pine Gap lease falling due on December 9, four days before the election. Which of course Fraser duly did.

The continuation of the reserve powers beyond the immediate crisis was supported by advice Kerr had received from Sir Garfield Barwick. That advice and the fact that Kerr had received it from someone other than the prime minister were both controversial. However, Kerr intended not only that an election was called, but that Fraser would be caretaker. His refusal to see the Speaker was extraordinary, without precedent and surely illegal.

While Rundle believes the Palace did have a role in dismissing Whitlam, the events can be explained by a story line which is not mentioned in Kerr’s reporting to the Queen.

There was controversy at the time over Pine Gap, because Whitlam was not a certainty to renew the lease. There was more than a suspicion that he favoured a non-aligned foreign policy in the Cold War. There was significant support for such a stance within the Labor Caucus.

In a related tangled web, there was a kerfuffle over the use of Pine Gap by the CIA for spying. Whitlam’s office were probing this and asked the head of the Defence, Sir Arthur Tange, for a list of CIA agents. They were given an “outer” list, which did not contain the names of deeper agents only known to Tange and the actual spy agencies.

The “outer” list did not include the name of Richard Stallings, inaugural head of Pine Gap, who was quietly living in Australia. What Tange did not know was that Whitlam’s office was already onto Stallings.

Former CIA official, Victor Marchetti, told journalists:

- Stallings joined the CIA’s covert action division after leaving Pine Gap and returned to Australia to try to influence politics. He had good contacts – a notation on his lapsed application for Australian citizenship read, “Mr Stallings is known to Mr Anthony and Mr Dunstan [the County Party leader and South Australian Labor Premier]”.

That was according to Brian Toohey’s 2015 article Arthur Tange and Gough Whitlam spy mystery: was there a crucial information gap?

Toohey’s article proceeds:

- The ‘gravest breach of security ever’

On November 2, Whitlam claimed the CIA had funded the Country Party, without giving evidence. He did not name Stallings. Anthony was the first politician to do so, telling journalists that Stallings was a friend who had rented his Canberra house. He said the two families holidayed together, but didn’t know that Stallings worked for the CIA. Tange apparently did not see any need to tell him.

On November 6, Anthony put a question on the parliamentary notice paper, challenging Whitlam to give evidence when Parliament resumed on November 11 that Stallings worked for the CIA.

Then:

- Whitlam prepared an answer on Anthony’s question on November 6. Later that day he read the proposed answer over the phone to a horrified Tange, making it clear Defence (i.e. Tange) had told him about Stallings. Tange then put an intense effort into trying to stop Whitlam giving that answer. He told Whitlam’s staff the PM would commit the “gravest breach of security ever” if he said the CIA ran Pine Gap, even though this fact was already public. He told Menadue, “The country will be cut adrift”.

Whitlam wanted the Australian people to know what was going on and fully intended to tell them. However, he never got to do it, because when parliament resumed on 11 November, he was the one cut adrift.

In November 1985, then Defence minister Kim Beazley said his department had studied issues raised by Toohey about events in 1975 and he would respond after discussions with his ministerial colleagues.

-

He then rang to say that several communications had been received from the US in early November, some of which were “suggestive” of an attempt to influence Australian politics, but there was “nothing conclusive”.

If the study is eventually released, it might throw more light on what ministers may not have been told because of Tange’s sometimes wildly ill-informed preoccupation with secrecy.

In Deborah Snow’s 2019 SMH article Tantalising secrets of Australia’s intelligence world revealed (about Toohey’s book Secret: The Making of Australia’s Security State) she says:

- Toohey stops short of saying that these behind-the-scenes dramas were a factor in the dismissal but he leaves the question hanging.

“I never at any stage say that the CIA overthrew the Whitlam government, what I’m trying to say is we don’t know, basically,” he tells the Herald and The Age. “There are lots of indications and lots of things that are suggestive but that’s not the same thing as being able to demonstrate it.”

However, we are effectively a client state of the US according to Toohey:

-

As well as canvassing what successive federal governments and their agencies have been keen to hide over the years, Toohey mounts a withering examination of Australia’s involvement in US-led combat missions in Vietnam, Korea and Iraq.

He is critical of the long-standing Australian government policy of striving for ever greater inter-operability with US military forces. Provocatively, he argues that the republican movement is “irrelevant” because the US “military-industrial-intelligence complex” has a “huge say” in whether Australian governments to go war, host bases, and what weapons they buy.

“The upshot is that Australia has surrendered much of its sovereignty to the US,” he claims. “The national security juggernaut has reached the point where Australia is now chained to the chariot wheels of the Pentagon.”

Rundle says that Kerr started life as “a working-class scholarship boy and a Stalinist sympathizer who became Trotskyist-aligned in the 1930s, but by the late 1940s, “he had become an anti-communist and a prominent member of CIA front group the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom.” Following the war he had a long association with US intelligence agencies, and without doubt became a CIA “asset”.

As such he did not have to be told what to do about the situation he faced with Whitlam in November 1975.

Australia pivots

Still, in Rundle’s Arena article The Dismissal: The Beginning of the Era of Total Surveillance he stops short of certainty on the matter, but assigns greater significance to the dismissal as a world event:

The strong possibility remains that Kerr terminated the Whitlam government early, in part so that a caretaker Fraser government would be in power when the leases of US bases came up on 9 December, and so that a CIA agent would not be named in the Australian parliament. That would appear to be how to read the dismissal: not primarily as a conflict between British and Australian power in a Commonwealth state but as part of the three decades of US dominance of the West via the spy agencies in the wake of the Second World War. One of Whitlam’s acts that angered the United States was withdrawing Australian cooperation from the destabilising of Chile’s Allende government in 1973. The dismissal can be seen as a soft form of that hard coup.

But equally it can be seen as something pointing to what were then future forms of power. Pine Gap was a new type of facility, the first part of what would become the capacity for total world surveillance that Edward Snowden has revealed is being conducted by the NSA. Political formations within Australia had been fighting for their independence for decades, from British rule, from crude US dominance. Pine Gap was a new form of power that undermined the capacity for states to achieve any independence, because their borders could not be maintained against mass surveillance. After Pine Gap was re-authorised, the Fraser government went on to authorise the ECHELON program, which drew Australia deeper into global surveillance on behalf of the United States, using a larger network of spy stations. The bases used the remoteness of Australian locations to gain clear surveillance quality, and the Australian jurisdiction to keep them clear of US constitutional controls. The dismissal as the ‘Pine Gap’ moment was the point at which we radically lost our capacity, in the Cold War, to chart an independent foreign policy and military course. The dismissal was an event for both Australia and the world, of far greater significance than is widely supposed. A defender of Kerr’s would write a book about him entitled Sir John Did His Duty. Indeed he did. But to whom?

Rundle fingers Kerr as an American stooge rather than a British stooge.

It seems naive to rule out Sir Arthur Tange’s involvement with Kerr, as Peter Davies does in Arthur Tange, the CIA and the Dismissal or with the Americans. Toohey reports that Tange did brief Kerr and seemed to know what the Americans were going to say before they said it.

For other accounts see green left and Workers Bush Telegraph. The latter is highly referenced, and seems to follow John Pilger’s account.

While it is unlikely that Whitlam would have cancelled the Pine Gap lease, he was not predictable. It is certain that he would have revealed Richard Stallings role.

Of course, Australia has depended on the American alliance for a lot longer than 1975. Rundle’s analysis raises the question as to whether hosting Pine Gap is compatible with having a truly independent foreign policy. I can’t imagine abandoning it.

This started as a ‘Salon’ item, but got out of control.

The absence of evidence is curious.

But the void is easily filled with rumour, speculation and tidbits.

Certainly President Nixon and H. Kissinger were displeased with the W Govt. On Whitlam’s side, he tended to be skittish; threatening to terminate the Pine Gap lease (though most likely to renew it).

John Kerr had to face the possibility that W would try to govern without supply. He consulted with Treasurer Hayden and the commercial Banks over the scheme to issue “IOU’s” to public servants in lieu of wages.

About 11 months earlier, Kerr had not been invited to an Executive Council meeting at which authority was issued to seek overseas loans (2 billion, big money in 1974) “for temporary purposes” thereby bypassing the Loans Council. So strange was that meeting that Dr Cairns stumbled into it uninvited and accidentally. At the thime he was Treasurer. The meeting was about a massive overseas loan.

Temporary? Oh indeed. Just building a national gas pipeline grid, developing mines, etc.

John Kerr was criticised for waving that Executive Council minute through… some folk alleged he had been tricked into an unconstitutional action.

Just some background….

BTW

Now that the Kerr/Charteris correspondence is public, it seems (to me) clear that

1. the Palace believed the reserve powers existed.

That was never disputed by PM Whitlam

2. Mr Kerr gave ample thought to various possibilities. Mr Charteris advised that dismissal could be used but only as a last resort.

Various commentators have suggested that the whole idea of dismissal was put into John Kerr’s head by the Palace. Balderdash.

The Opposition spokesperson on law had set out a detailed case that if supply could not be obtained then the PM must advise a HOR election and if he wouldn’t, then the GG must dismiss the PM and arrange an election. This “Ellicott opinion” was widely discussed in the Press at the time.

It was neither arcane nor a bolt from the blue.

Mr Whitlam as ex-PM told some of his dismissed Ministers, “He’s done a Game on ys”, referring to the dismissal of Premier Lang by Governor Game (NSW, 1930s)

All that being said, Ambi, and thankyou for the information, did it have to happen before Question Time on 11 November?

That’s something I’ve often wondered, Brian.

Some folk (Mr Whitlam included?) said the GG acted too early.

They claim there was still a few weeks of supply left….

I’ve never seen any technical information on that.

When was the next Public Service pay day?

How many $ were available?

Armed Forces wages?

Contractors on Govt tenders expecting payments?

???

Perhaps the GG might have waited until a few days later, e.g. Friday? But if he had decided that the proposed half-Senate election was unlikely to break the deadlock between HoR and Senate, what could he do?

Ask the PM’s opinion? (No need, really: the PM had announced he would seek a half-Senate election. He had also rejected a compromise from Fraser – something about the PM promising a parliamentary delay until July 1976 would occur.)

Warn that dismissal was on its way?

Call Fraser and Whitlam into his study for a stern talk?

In the Charteris/Kerr correspondence, Kerr explains that Fraser is manoeuvering in the Senate with the express and sole purpose of forcing a general election. There is no doubt on that score. The voters knew it too.

The Palace has no comment, as far as I know, to make about the States’ manoeuvres which led to the Opposition having a couple of handy extra Senate seats.

On Pine Gap, if the Whitlam Govt intended to renew the lease, why on earth did Gough threaten (in Parlt) not to renew? Was he currying favour with his backbench? Was he merely grandstanding?

He hadn’t indicated, as far as I know, that he wanted to tear up ANZUS and take the nation on a “neutralist” path in the Cold War.

By the way, I would trust the late Des Ball, and Brian Toohey, and historians/defence experts of that era, way……. above John Pilger or indeed Guy Rundle.

I believe there are biographies of Arthur Tange, Garfield Barwick, Malcolm Fraser available. Certainly memoirs by:

Mr Whitlam

John Kerr

Bill Hayden

“Diamond” Jim McClelland

Tom Uren

etc

(Have to admit that after reading a biography of Lionel Murphy by Jenny Hocking, I thought it was ‘hagiography’; hence didn’t read her two volume biography of Gough Whitlam.)

Ambi, I have not read as much as you have in this area, but think very highly of Toohey, thought highly of Des Ball, and share your reservations about Guy Rundle and especially John Pilger.

Rundle disses Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston on the Dismissal, and I think on that one he’s probably more right than wrong.

So many conspiracy theories!!

Kerr was vindicated by the 75 election allowing Australians to demonstrate buyers remorse.

They had a choice between a Keynesian and an outright Socialist so chose the lesser of two weevils.

Fraser a Keynesian? Fraser, who at the time was an avid follower of Ayn Rand? (He evolved, thank goodness)

You obviously weren’t there at the time and you have no idea what you’re talking about (as usual).

[Notes for Jumpy: that last sentence is not an ad hominem argument. It’s a critique of your abysmal grasp of history, which seems to arise from your infantile need to fit everything into your binary world view.]

I again recommend to serious commenters here the ABC podcast The Eleventh.

From Wikipedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Fraser#Prime_Minister_(1975–1983)

Check the prime sources yourself.

Now give yourself another uppercut, but harder this time.

Not really relevant, but some wags on Fleet Street invented the verb to pilgerise,

meaning to take a couple of facts and build an overwrought, dramatic tale.

Or as some folk say, “fake news”.

Brian, I haven’t read very much. E.g. Jenny Hocking, Guy Rundle and other commentators have dived much deeper.

What I’m interested in, is trying to understand the flaws of each Govt, because I still hold that any new Govt should try to learn from past errors made by its Party – and if relevant, past errors by other Parties.

Yes, it’s a very quaint idea.

It’s useful to learn from one’s own mistakes; even better to learn from other peoples/ mistakes..

Jumpy: from 1975 to 1979, Keynesian policies, in greater or lesser degree, held sway in Western circles. Not only in Scandinavia, but across Europe and North America. PM Fraser and his young Treasurer were probably following Treasury Dept advice, with the Govt’s own minor variations.

(With the stark example foremost in many Govt minds of the Loans Affair, which basically destroyed the credibility of Gough’s Govt, and helped deliver that Dec 1975 landslide to the Coalition Parties. A major element of that ‘Affair’ was the search for loans via ‘funny money’ intermediaries [translation: con men], against the advice of Treasury, which had pages of restrictions/guidelines/principles/double checks on overseas loans. Aussie Govts had been borrowing for decades; the idea wasn’t novel.)

Jumpy: “Fraser practised Keynesian economics during his time as Prime Minister,[21] in part demonstrated by running budget deficits throughout his term as Prime Minister.[22] He was the Liberal Party’s last Keynesian Prime Minister. ”

The problem was that Keynesian economics was not what was needed to fight stagflation. In the Australian version stagflation was the result of business raising prices in response to pay rises and unions expecting pay rises to compensate for price rises. Part of the problem was that unions detested Frazer because of the dismissal.

It took Bob Hawke to beat stagflation. He could do it because the unions trusted him and he was good at getting unions and business to start co-operating.

I stand corrected. Apparently the austerity measures I remember Fraser implementing were Keynesian, and his famous pronouncement that life wasn’t meant to be easy owed nothing to Ayn Rand.

I was wrong. I beg this forum’s forgiveness.

What interested me at the end of this excursion triggered by Rundle was not whether Kerr was justified etc but this:

Rundle’s analysis raises the question as to whether hosting Pine Gap is compatible with having a truly independent foreign policy. I can’t imagine abandoning it.

Mr Fraser had several influences. He seemed stern and sad in the 60s and 70s.

An anecdote from his youth: apparently his Dad once left him for a while on a snake-infested island in a river….. Regardless of Ms Rand’s influence, it seems Dad also may have believed life was meant to be a bit of a b*gger.

Cheerio from the State of Malcolm Fraser, Harold Holt, Bob Menzies, Lord Casey, Stanley Bruce, Henry Bolte, Dick Hamer; Jim Cairns, Moss Cass, Barry Jones, John Button, Bob Hawke; B. A. Santamaria, Archbishop Mannix, Manning Clark, Frank Hardy/John Wren, Peter Hollingworth, Zelman Cowan, et al.

Ambigulous on the Premier Palaszczuk is ‘absolutely furious’ thread

But not the blocking of supply. If memory serves, once the Tories had won the election they changed the rules to ensure that particular conflict can’t happen again.

The rules were changed to stop blocking of supply and to take away from premiers the right to appoint whoever they liked to replace a Senator who left between elections.

The Frazer and his government were weakened by the way he got into power.

Kerr would have had more respect if he had resigned after Frazer had been elected on the grounds that he had become a divisive figure and governors should be a uniting figure.

Crikey!

Are you saying that in October 75 the Senate had the power to defer Supply and now it doesn’t??

That’s interesting.

Thanks zoot.

Thanks John.

So Mr Fraser and Mr Anthony were b beneficiaries of two quirks which were later corrected by consensus.

Here’s something I hadn’t seen until recently.

Tom Gilling, “Project Rainfall. The Secret History of Pine Gap.”

Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2019

p.141

On 3rd April 1974, asked in the House of Reps about a proposal for a joint “Australian-Soviet station” in Australia, PM Whitlam “then veered away from his prepared reply with an incendiary statement”: The Australian Government takes the attitude that there should not be foreign military bases, stations, installations in Australia. We honour agreements covering existing stations. We do not favour the extension or prolongation of any of those existing pones. The agreements stand, but there will not be extensions or proliferations.

Gilling comments: “That the ruling out of ‘extensions’ to existing agreements was an off-the-cuff remark, a departure from the script, made it more, not less, ominous to the Americans, because Whitlam was in charge and his words appeared to have the weight of personal conviction.”