I think I ignored Anzac Day last year, on the blog, that is. I think I grew up as patriotic as the rest of the community, despite being embedded in a community of ‘German’ farmers, who were mostly third generation Australians. Anyway their services were definitely not required even in the Second World War. Indeed I understand that my father may have been involved in some Dad’s Army type exercises in case of a Japanese invasion. But when the authorities discovered there were Germans involved, that was the end of that.

However, apart from those of German origin very few Australian families escaped losing relatives on the battlefields of northern France and Flanders, our extended family by marriage amongst them.

The Australian War Memorial frames Passchendaele as an almost universal experience where in a concentrated area in three and a half months around a million and a half men experienced war. Total casualties are estimated at about 275,000 British and Commonwealth and about 200,000 German. All for a gain of 8 kilometres in the line, which was later given up.

The French were not involved. It happened from July to November 1917, with the Americans on the way but yet to come in 1918. The War Memorial piece continues:

- 38,000 Australians, 15,654 Canadians and 5,300 New Zealanders fell there, either killed, wounded or missing. Especially for these smaller nations, Passchendaele was their most costly engagement of the war, indeed their entire military history. Because of the scale of losses and the fact that the Commonwealth nations committed their entire forces to the campaign, it was sadly not uncommon for families to lose several members during it (see article on Polygon Wood battle).

With these statistics in mind it is little wonder that after the war ended, the Ypres-Passchendaele area quickly became the focal point for commemoration for all the nations involved in this terrible campaign, and remains so to this day.

To commemorate the spirit of Anzac Day Richard Fidler’s interview with Australian author Paul Ham on the bloody futility of Battle of Passchendaele was replayed today (Monday) on local ABC radio, and repeated on RN in the afternoon.

Ham says that the ostensible reason for trying to advance in Flanders was to disrupt the German U-boat campaign. He says that by late 1917 the strategy was actually pointless.

Retracing the genesis of the Passchendaele campaign takes us back to the British blockade of German shipping, which, he says was the most successful part of the whole war. He says the accepted figure is that 800,000 Germans died because of the blockade.

The Germans responded by using their U-boats to attack merchant shipping destined for Britain. Two of the U-boat ports used by the Germans were in Flanders. However, he says, by the summer of 1917 the U-boat strategy had been effectively countered by organising merchant shipping in convoys with navy escorts. In any case the Flanders ports were not the only ones used by the Germans.

By this time much blood had been spilled in the attempt to take Passchendaele which lay on the last ridge east of Ypres that failure had become unthinkable, so it became more symbolic than necessary for military strategy reasons.

Ham explains that Passchendaele was also mixed up in the toxic relationship between the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force. The PM thought Haig was a butcher after Verdun, and opposed the Passchendaele strategy, but for complex reasons which Ham explains, Haig had his way.

Ham says a secondary reason was given – keep the Germans busy while the French recovered further south.

Ham’s big claim, though, is that Haig was consciously fighting the war as a war of attrition. The casualty count did not matter as long as the Germans ran out of troops before he did, and he had larger populations to draw from in the Commonwealth, with the prospect of the Americans to come, and come they did the following year at the rate of 10,000 a day. ‘Normal’ casualties during a major campaign were reckoned at 20 to 50,000 a week. Indeed when casualties fell to one or two thousand, Haig worried whether his troops were showing sufficient attacking vigour.

Ham’s assessment is that both sides lost at Passchendaele, which made it inevitable that peace would be sought.

Final responsibility, says Ham, must lie with Lloyd George, who could have stopped the slaughter, but didn’t.

It is arguable that the critical factors in determining the outcome of the war were the naval blockade of Germany and the success of British convoy system, which drained Germany of resources, industrial production capacity and sapped morale, plus the arrival of the Americans, which more than offset the release of German soldiers from the Eastern front as Russia dropped out of the war.

Germany still had the strength to mount a spring offensive in 1918 to pre-empt the arrival of the Americans, but it foundered 120 km short of Paris. At that point you could argue that the attrition strategy of the earlier years was a factor, but a very expensive one.

There is another story about how Germany effectively became a military dictatorship during the war, but was politically falling apart in 1918, culminating in the Kaiser doing a runner. Politically, Germany went from being an empire to a republic of sorts, run for many years by an elected democratic socialist until the emergence of Hitler. But that is another story, as is the recasting of the map in Europe and especially in the Middle East.

Wikipedia has a detailed entry on the Battle of Passchendaele and indeed on World War I. In the entry World War I casualties we are told:

- The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was more than 38 million: there were over 17 million deaths and 20 million wounded, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history.

I’ll post this now and hopefully find a few relevant photos later in the day.

Update: Unless otherwise noted the photos are courtesy of my rellies, who visited the area in 2015.

The featured image at the head of the post is a photo by Frank Hurley of Australian gunners on a duckboard track in Château Wood near Hooge, 29 October 1917 from Wikipedia:

War memorial Ypres (leper in Dutch):

The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing is a war memorial in Ypres, Belgium, dedicated to the British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the Ypres Salient of World War I and whose graves are unknown. Photo by Johan Bakker:

The Captain Cook Restaurant is a good place to relax after Menin Gate:

Not too many customers inside that day:

A shell hole at Hill 60:

A memorial to Australian tunnellers:

Ham says that miners were brought in from Britain and elsewhere to tunnel under the German lines in order to set explosives. On one occasion a whole hill was blown away in a blast that was heard in London.

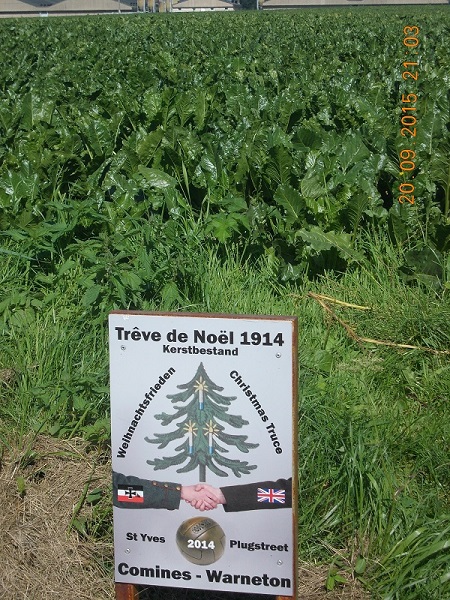

The Christmas truce in 1914 commemorated:

The Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 was actually the Third Battle of Ypres. That image shows fertile farmlands, on show in the next image:

August 1917 saw the heaviest rain in 70 years. The battlefield turned into a bog that literally swallowed up horses, used to pull canon, and men. Ham says it was bad enough that the soldiers had to shoot their beloved horses, but he says they even had to shoot their comrades as they sank up to their necks and could not be pulled out.

Black Watch Corner, near Polygon Wood:

The Battle of Polygon Wood took place during the second phase of the Battle of Passchendaele, from 26 September to 3 October 1917.

A monument commemorating the involvement of the Fifth Australian Division:

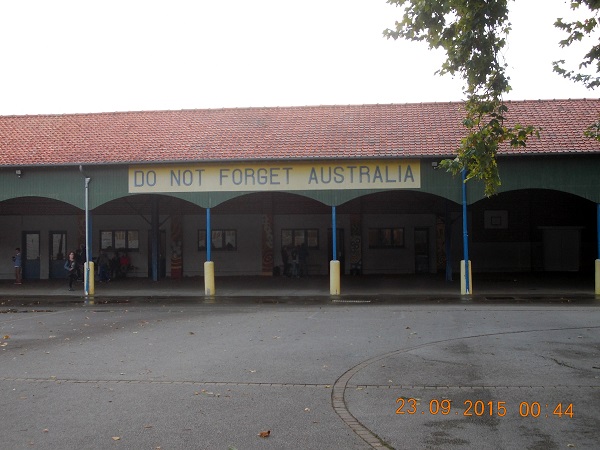

Australians are well remembered by the people in the area as this school at Villers-Bretonneux shows:

Villers-Bretonneux is another related story, and is where commemorations have regularly been held since 2008 to balance Gallipoli. I’ll finish with a photo of Australian war graves:

My sister-in-law’s father survived Passchendaele. My wife lost two uncles, one killed in that war zone and one later from wounds. Unfortunately they died before she was born, and sadly her mother seldom spoke of them. It all happened in an unnecessary war that everyone at the time knew was coming.

Homo sapiens, not so bright, but I think the upheavals and loss in the two great wars in Europe, and indeed their violent history over two thousand years, now underpin a strong and abiding impulse for peace in continental Europe.

Part of the problem was that the poms had spent years fighting poorly armed opponents as part of expanding and maintaining the empire. In most cases what this meant was simple tactics like letting your opponents charge against your well armed position or breaking your opponents by charging. It meant people like Haig could get promoted by taking a brave, but not necessarily smart, stand and depending on superior weapons and determination to win. He could also get results without having to care much about his soldiers.

WWI was a new game where the old tactics that depended on the bravery of soldiers didn’t work. The war was only won when outsiders like Monash who understood the implications of the new technology and cared about soldiers lives became influential.

Photos now up.

John, certainly there were new technologies never before deployed at scale, such as the machine gun, gas, bigger and better canon, and towards the end tanks, also aircraft to some degree.

Ham said that the command was remote from the battlefield, and they didn’t truly understand the nature of the carnage that was taking place.

I know movies aren’t reliably accurate but Beneath Hill 60 tries hard to be I’m told.

It looks at the Tunnellers.

I watched it yesterday and it’s done well but it’s hard to say I enjoyed it given the content.

The one time my wife and I were driving past signs to war graves in northern France, we couldn’t face visiting any of those vast cemeteries. Two of my mother-in-law’s uncles were killed on those fields.

So many families devastated.

If we’re citing films, “Paths of Glory” is powerful, perhaps more so because shot in B&W. Soldiers court-martial led and executed pour encourager les autres (“to encourage the others”).

Jumpy, haven’t seen it, but I’ve heard the film is pretty accurate.

Ambigulous, I can do cemeteries for some reason, but in 2015 some of us went to Auschwitz. I’d steeled myself to process it at a cognitive level, but when you see a room piled up a metre or more deep with booties from babies and toddlers, right next to a room with piles of actual human hair, that breaks through somewhat.

My grandfather was an electrician in the tunneling and was gassed at one stage. He rarely talked about the war.

By contrast my father who fought in WWII told war stories all the time. (usually funny, even when the actual incident was serious – He was badly enough wounded to spend a year in hospital but his story was about his mates patching the inlet wound and forgetting to patch the exit wound.)

My take is that WWI was a pointless war fought in an horrific way while WWII really was a battle between good and evil.

You’re a stronger man than I am, Brian.

Never forget.

Lest we forget.

Ambigulous, I’d have to say that the dead-pan delivery of the Polish tour guide helped. Also the place is run over by tourists, and when you come into Auschwitz there is a huge Kentucky Fried Chicken advertisement beside the road, which is not the best.

John, one of my theories is that there were no natural boundaries either side of Germany on the northern European plain, although they’ve now drawn a line on the Oder-Niesse line, and most of the Germans east of there were kicked out or had to leave.

In the west, the concession of Alsace-Lorraine to the French tidied that up a bit.

Some people claim that WWI was war by timetable.

OK. The article talks about some of the other factors that contributed to the war and its incredible destructiveness and the stalemate caused by the initial dominance of defense technology until further developments swung the balance towards the technology that allowed the tank based blitzkrieg tactics tactics of Monash to break the German defenses and end the war.

John, many historians since Taylor have had a crack at uncovering the causes of WWI, but there is no doubt the railways were a factor in how it played out.

I recall in reading Prussian history that railway lines were established between the main industrial and population centres by 1850, built by private enterprise. The Prussian king, however, saw that more was needed for defence purposes and wanted to borrow money to push the lines further. The constitution prohibited him from incurring debt without consulting parliament. He thought the necessity to consult parliament was an insult to him.

However, the impasse led to the situation where you had a representative parliament of sorts, but the King appointed the prime minister. Hence they got Bismarck, who ran the show.

I believe in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 France had the machine gun, though not widely deployed, but it was Prussia’s ability to shift men and arms that overwhelmed them.

You could argue that railways were a critical factor which enabled modern Germany to rise as a unified state.

Michael Portillo has been examining the role of railways in WWI – Railways of the Great War, 7:30 pm Fridays SBS – which should be available on demand.

Last program is Friday 28 April.

It’s been fascinating. Well worth a look.