By 2040 three quarters of our energy will still come from fossil fuels, with global energy demand increasing by 37% and emissions increasing by 20%, according to the IEA world energy outlook 2014. IEA Chief Economist Fatih Birol:

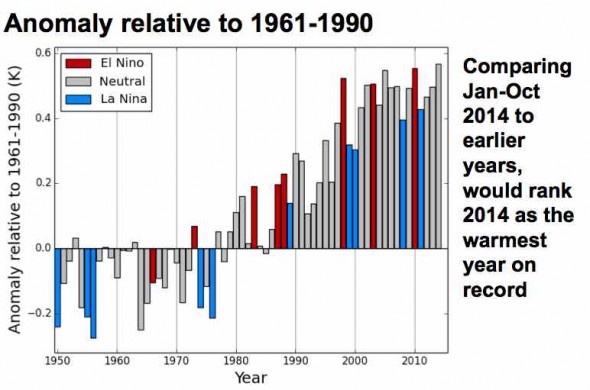

The International Energy Agency estimates the planet is on track to warm by 3.6 degrees Celsius. Investment in renewables needs to quadruple to an average of $1.6 trillion every year through 2040 to meet the 2-degree target.

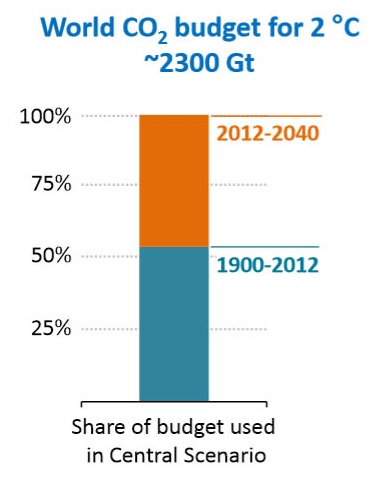

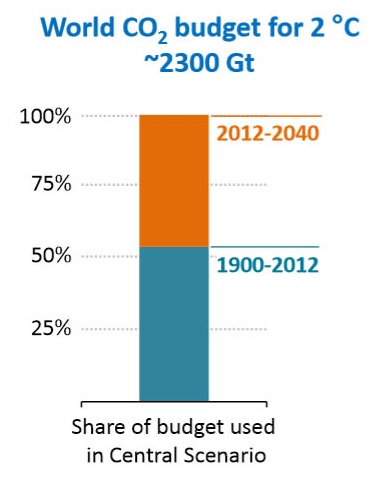

Taking the world’s CO2 budget to limit warming to 2°C as 2,300 Gt of CO2 from 1900, we have 1,000 Gt left from 2014, and are set to use all of it by 2040:

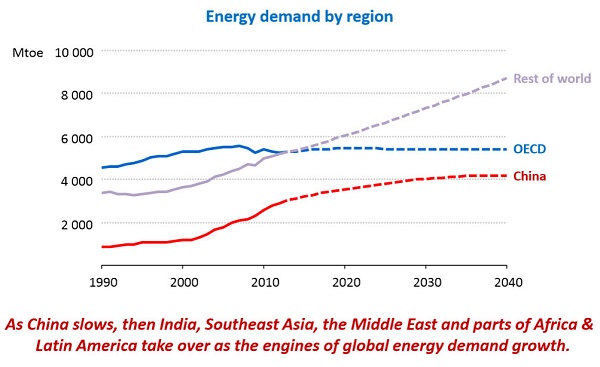

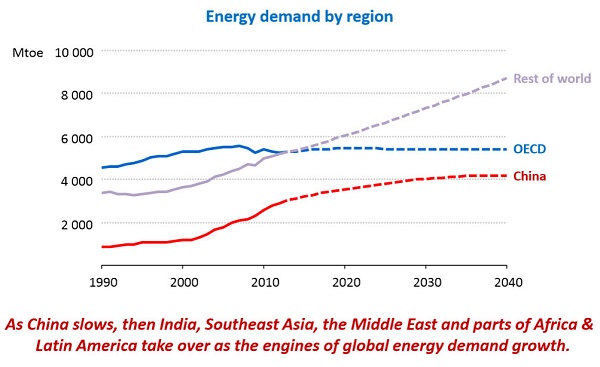

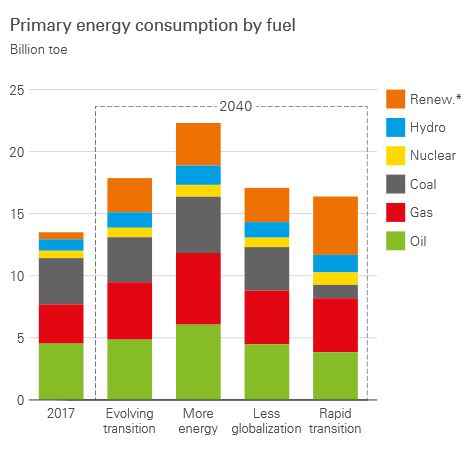

Overall energy demand is set to grow by 1% pa, about half the growth experienced in recent decades. Demand is flat in the OECD, slowing in China, but growing vigorously in the rest of the world:

By 2040, the world’s energy supply mix will divide into four almost-equal parts: oil, gas, coal and low-carbon sources, including renewables, hydro and nuclear. Growth in oil and coal will taper to nothing, but gas will grow vigorously, with demand increasing by 50% by 2040.

Oil

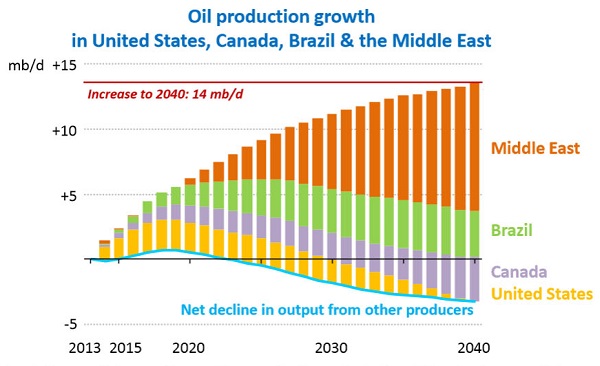

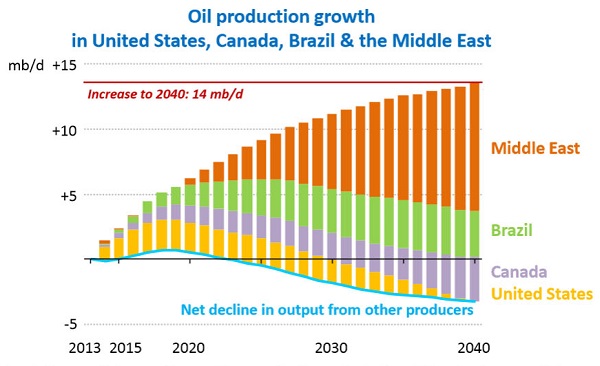

World oil supply rises to 104 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2040, but hinges critically on investments in the Middle East. As tight oil output in the United States levels off, and non-OPEC supply falls back in the 2020s, the Middle East becomes the major source of supply growth. Growth in world oil demand slows to a near halt by 2040: demand in many of today’s largest consumers either already being in long-term decline by 2040 (the United States, European Union and Japan) or having essentially reached a plateau (China, Russia and Brazil). China overtakes the United States as the largest oil consumer around 2030 but, as its demand growth slows, India emerges as a key driver of growth, as do sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

The changes in supply are shown graphically below:

Concern is expressed that ISIS is deterring investment in production in Iraq.

Oil prices are likely to rebound, averaging $82.50 a barrel in 2015 and rising to near $100 in the coming years.

Coal

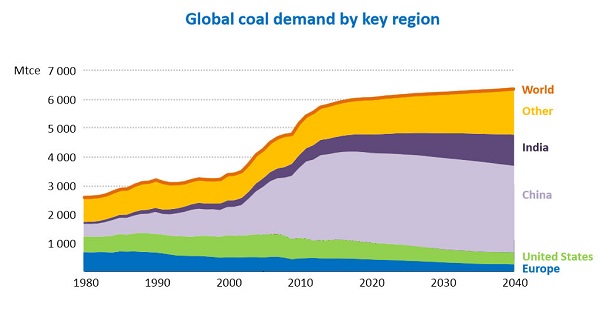

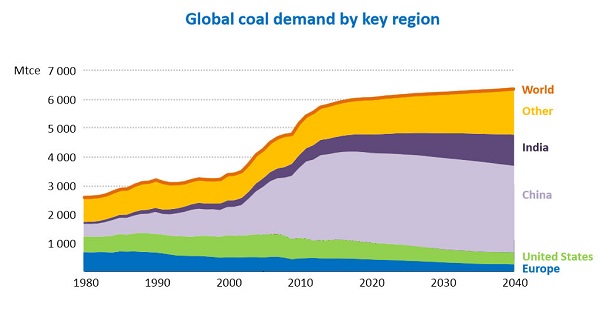

Global coal demand will grow by 15% to 2040, but almost two-thirds of the increase will occur over the next 10 years.

Chinese coal demand plateaus at just over 50% of global consumption, before falling back after 2030. Demand declines in the OECD, including the United States, where coal use for electricity generation plunges by more than one-third. India overtakes the United States as the world’s second-biggest coal consumer before 2020, and soon after surpasses China as the largest importer.

Australia will pass Indonesia to once again become the largest exporter by 2030.

The graph shows the importance of China in the global market:

The graph also highlights the folly of India and developing countries polluting their way to prosperity.

Gas

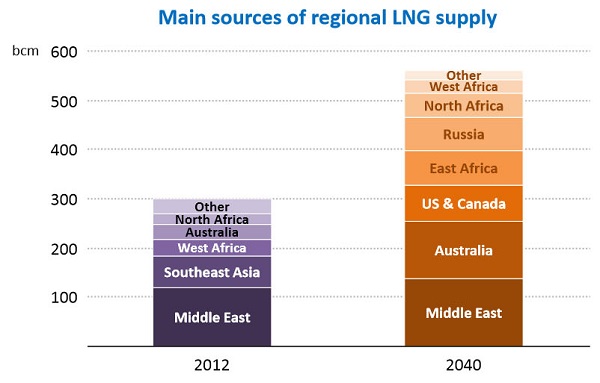

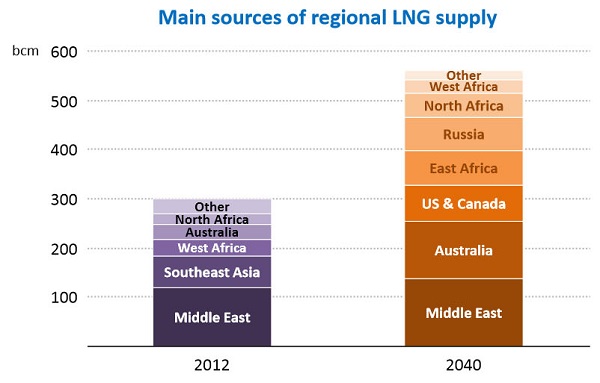

The key uncertainty – outside North America – is whether gas can be made available at prices that are attractive to consumers while still offering incentives for the necessary large capital-intensive investments in gas supply; this is an issue of domestic regulation in many of the emerging non-OECD markets, notably in India and across the Middle East, as well as a concern in international trade.

If these uncertainties are met the world gas market will be transformed with Australia a major beneficiary:

60% of gas will be ‘unconventional’, meaning shale and coal seam.

There is uncertainty about the $900 billion per year in upstream oil and gas development needed by the 2030s to meet projected demand.

Nuclear

The IEA sees global nuclear power capacity increasing by almost 60%. However, its share of global electricity generation will rise by just one percentage point to 12%.

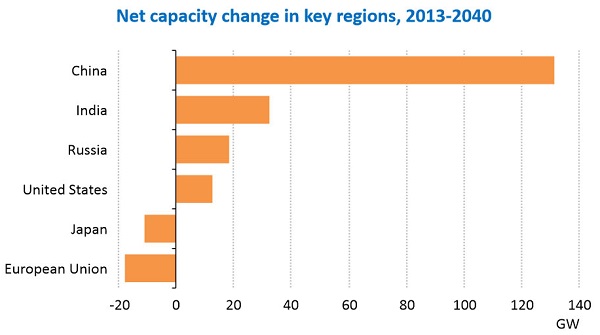

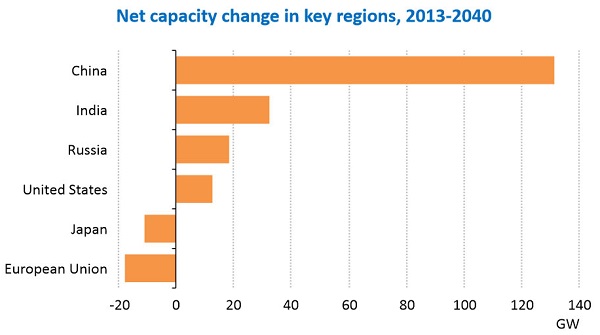

Some 38% of existing capacity will be retired. Once again the importance of China is seen in this graph of the changes in capacity of the key players:

Renewables

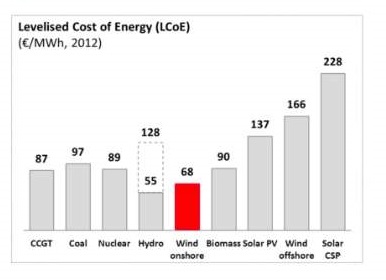

Renewables will account for almost half of the increase in total electricity generation to 2040.

The share of renewables in power generation increases most in OECD countries, reaching 37%, and their growth is equivalent to the entire net increase in OECD electricity supply. However, generation from renewables grows more than twice as much in non-OECD countries, led by China, India, Latin America and Africa. Globally, wind power accounts for the largest share of growth in renewables-based generation (34%), followed by hydropower (30%) and solar technologies (18%).

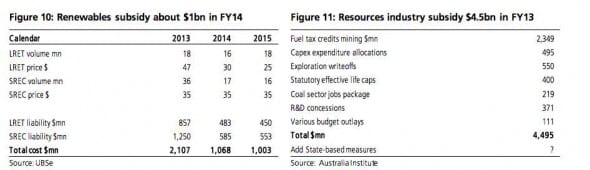

Global subsidies amount to $120 billion compared to $550 billion for fossil fuels.

The growth in hydropower is an ecological concern.

Paris and prices

The Executive Summary leads with a statement about the uncertainty of energy futures in very troubled times, so the IEA forecasts must be seen in this light. The IEA is urging strong intervention by decision makers in the UNFCCC conference in Paris in December, to avoid a climate catastrophe. They call it the last chance. Worth noting here is that the 2011 World Energy Outlook found that all new power supply built after 2017 would need to be zero carbon.

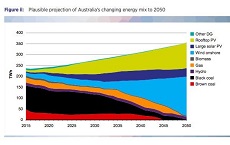

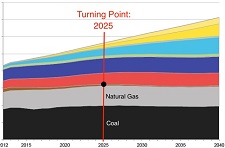

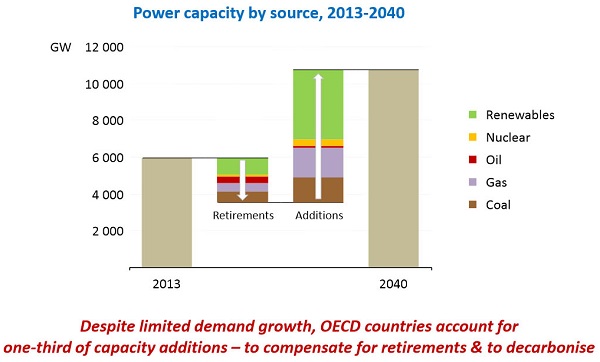

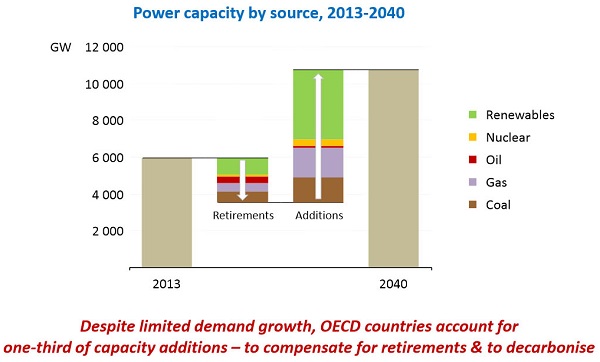

I’m not sure the IEA is fully aware of how cheap renewable technologies are becoming, and how disruptive these technologies will be. Nevertheless their mainstream future, dubbed the “central scenario”, already has renewables comprising about half of new capacity. The changing pattern in power supply is captured as follows:

Clearly we are relying too much on gas and coal for new supply, and we need to retire more dirty power, especially brown coal.

Sources

Unfortunately one can’t read the full report without buying it so I’ve had to make do with links, mostly from this page. The Executive Summary provides the story in words, the pictures all come from the London presentation.

See also Peter Hannam at the SMH, my 2011 post on the 2011 report and Climate clippings 103, Item 4 for a brief treatment of World Energy Investment Outlook 2014.

Also relevant is Mark Diesendorf’s plan for 100% renewable energy in Australia.

BP’s vision

Finally, BP has taken a look at the future. What they find is not dissimilar to the IEA, just heading down the crapper a bit faster. They see global energy consumption in 2035 as 37% greater than now and CO2 emissions 25% more. They see a clear role for themselves to make a buck while cooking the planet.

Continue reading BP sees coal demand continuing, even more so oil and gas

Continue reading BP sees coal demand continuing, even more so oil and gas