German critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin, who purchased the Angelus Novus (new Angel) print in 1921, interprets it this way:

- A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

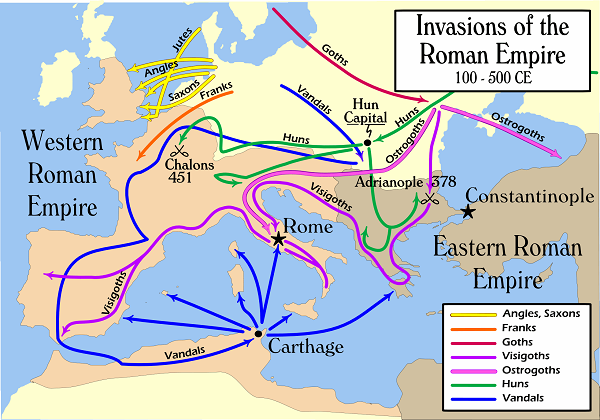

Arguably Continental Europe was wracked by two millennia of war and carnage from the time the Germanic tribes came streaming out of the north. We had the Goths, the Franks, the Vikings, the Burgundians, the Vandals, the Saxons, the Alemanni who settled in what is now Alsace and Northern Switzerland, and the Lombards in Italy, plus Attila the Hun, Genghis Khan, the Saracens and the Turks. No doubt that is incomplete, but here’s the flavour:

In modern times, Europe was devastated by the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) by the Seven Years War (1756-1763) which is widely considered to be the first global war, while locally Prussia was seeking greater dominance than Austria, with Austria supported by the French and the Russians, resolving issues left over from the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748).

Following nearly four decades of relative peace in Europe, the place erupted again with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, which culminated (leaving aside Napoleon’s reprise at Waterloo) in the Battle of Leipzig (1813), a massive battle for those times involving 560,000 soldiers and resulting in 80,000 to 110,000 total killed, wounded, or missing.

That was followed by a century of relative peace, with the Age of Reason combined with the industrial revolution giving a time of unparalleled peace and progress. That is if you ignore what Europe did in conquering, pillaging and subduing the rest of the planet in the colonial project.

Then came the essentially pointless World War I, with some 68 million belligerents and around 40 million military and civilian casualties. Military technology had ‘improved, with the introduction of machine guns, tanks, gas, hand grenades, aeroplanes and submarines, so there was industrial scale killing.

Pessimism about what ‘progress’ had meant to humankind was natural after the war to end all wars. Oswald Spengler’s best seller The Decline of the West was published in two volumes, in 1918 and 1922, but was in fact conceptualised first in 1911. Spengler characterises Western civilisation as Faustian, after the German legend stemming from the 16th century and popularised by Christopher Marlowe in his play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (around 1587). Generally:

- The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroads, exchanging his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. The Faust legend has been the basis for many literary, artistic, cinematic, and musical works that have reinterpreted it through the ages. “Faust” and the adjective “Faustian” imply sacrificing spiritual values for power, knowledge, or material gain.

According to Spengler:

- the Western world is ending and we are witnessing the final season, the “winter” of Faustian Civilization. In Spengler’s depiction, Western Man is a proud but tragic figure because, while he strives and creates, he secretly knows the actual goal will never be reached.

Climate scientist James Hansen constantly refers to our Faustian bargain with the use of fossil fuels.

Around that time TS Eliot penned The Waste Land in 1922, followed by The Hollow Men in 1925, Franz Kafka explored themes of alienation, existential anxiety, guilt, and absurdity. However, no-one captured the essential questioning of the human project more pithily than the Swiss-German artist Paul Klee in his painting Angelus Novus in 1920.

Walter Benjamin, purchased the print in 1921, and wrote his comment cited above in 1940, near the end of his life, fleeing the Nazis. Benjamin, raised in a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin, was:

- an eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish mysticism, Benjamin made enduring and influential contributions to aesthetic theory, literary criticism, and historical materialism. He was associated with the Frankfurt School, and also maintained formative friendships with thinkers such as playwright Bertolt Brecht and Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem. He was also related to German political theorist and philosopher Hannah Arendt through her first marriage to Benjamin’s cousin Günther Anders.

His literary criticism included essays on Baudelaire, Goethe, Kafka, Kraus, Leskov, Proust, Walser, and translation theory. Plenty to chew on there.

Before he wrote the comment on Angelus Novus he was witness to the exuberance of the 1920s, the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, when JK Galbraith said that they all thought capitalism had failed and was finished. Followed by the rise of Fascism.

I set out on this track because John Davidson in a comment posted a link to Stan Grant’s article We choose our history to suit who we are, but ‘the great Australian’ silence is slowly being broken which riffed on Angelus Novus and Benjamin’s comment, referencing a shared panel discussion with

-

Indigenous scholar Marcia Langton and historian Henry Reynolds, whose work has challenged us to look to the other side of the frontier to tell another truth of invasion and massacre on our country.

We struggle under the weight of our troubled history, Grant said, later referencing Sisyphus:

- We cannot change the past and we cannot let it go. Like Sisyphus we are condemned to bear its load for eternity.

(Actually Sisyphus rolled the stone up the hill, only to see it slip from his grasp and roll down again, he didn’t carry it.)

So, says Grant, we are left with the same dilemma Benjamin had after fleeing the Nazis twice:

- He left us with his Angelus Novus — the Angel of History: A warning that our eyes cannot turn to the future when they are fixed so deadly on the past.

Stan is right in that resolving matters will require truth-telling and reparations. Beyond that lies reconciliation and with a bit of luck, forgiveness. Only then can we all own the past, the whole 300,000 years of it and beyond.

We can’t change what happened, but we can change how we view it, and accept that it has forged who we are.

Perhaps we can learn from the French and the Germans, who fought each other for millennia, then in 1951, with four friends, started the European Coal and Steel Community to “make war not only unthinkable but materially impossible”.

Success in this relationship has now seen French President Emmanuel Macron grant his good friend Angela Merkel the Grand Cross, the highest distinction of the Legion d’Honneur, France’s chief honour.

This would have been impossible 16 years ago, when Merkel came to the job.

Yes, in Australia we need a treaty with the First Nations people that makes Australia whole and one.

Then let a thousand flowers bloom. We can look to the future rather than fixating on the past, and truly become our best selves, individually and together.

However, the insights of Klee and Benjamin are still relevant today, to the whole of humanity, only more so.

Finally, some brief comments.

First, I don’t believe Benjamin was referring to the Nazis in his comment, rather, European Civilisation as it manifested itself in the 20th century.

Second, There is an insightful article in JAMA Psychiatry on what Angelus Novus meant to Klee and Benjamin. Klee served in the war under the Saxon king (Germany was an empire with four kings at that time). After Klee’s close friend and fellow artist, Franz Marc, was killed by a grenade at the Battle of Verdun, Klee engaged in a period of soul searching and reflecting on their differences in personality and style:

- What my art probably lacks is a kind of passionate humanity. I don’t love animals and every sort of creature with an earthly warmth [as he did]. I tend rather to dissolve into the whole of creation. . . . I place myself at [its] remote starting point. . . . Neither orthodoxies nor heresies exist there.

Klee had a lifelong interest in angels.

Third, Grant talks about the weight of our history upon us. On the contrary, I would suggest, most of us carry the weight rather lightly.

This is where Grant’s call for recognition of First Nations people, from 65,000 years ago to the post-colonial period, and now the present and emerging.

Fourth, Stan Grant does good work, but I find his constant literary and philosophical quotes distracting. At times they confuse his argument rather than clarifying. Waleed Aly and Scott Stephens recently spent 54 minutes discussing What are we doing when we “quote”? with Professor Bronwyn, Lea Head of the School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland. She is the Poetry Editor at the University of Queensland Press.

The question is complex, and several things may be happening simultaneously, some positive, and some negative.

It’s ironic that Benjamin had that characteristic in spades, according to Hannah Arendt’s brief eulogy in Men in Dark Times, essays on Karl Jaspers, Rosa Luxemburg, Pope John XXIII, Isak Dinesen, Bertolt Brecht, Randall Jarrell, and others whose lives and work. illuminated the early part of the century.

In this case Grant appropriates what Klee and Benjamin did, then rips it out of context, which gives me unease.

Fifth, I’m told that Jewish thought sees the past in time as existing only in the present, and as such, yes, it can be changed. We need to own it and recognise it as a gift.

John, in brief, the answer to your question on the other thread, is that yes there will be positives for all of us.

As there is now for the Europeans. However, the question of ‘progress’ when facing catastrophic threats like climate change and the other global crises as per Julian Cribb’s Surviving the 21st Century now present a challenge.

Brian: Looking at past evils can reduce outcomes that produce more evil. Think of Israel, a country created to compensate for the evil heaped upon the Jews by a whole raft of European countries. A country created by the urging of Zionists who believed that the Jews would only find peace if they returned to the holy land.

Problem was that those that wanted to compensate the Jew thought it was OK to compensate by gifting land where the Palestinians had lived for thousands of years instead of gifting land from countries that had done evil to the Jews.

The outcome has been very damaging and contributed to problems well away from Iserael.

John, doing harm to others is never the best solution.

We’ve reached a stage where the nation state is our prime political entity, but the world is now networked thoroughly, and in many places ethnically mixed.

It is said that the modern nation state came into being at the end of the Thirty Years War, which ended with the Peace of Westphalia, the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. It is known as Westphalian sovereignty, or the Westphalian system of government.

It perhaps reached its final form with universal suffrage in many democracies from about 1920. However to Klee, Benjamin and others the outer form papered over trouble within.

To take the story through to the present it may be useful to look at the work of economist Adam Tooze in Crashed: How a decade of financial crises changed the world. This review by Shahin Vallée of the LSE takes the causes back to the breakdown of the Bretton Woods arrangements in 1970.

Yanis Varoufakis says:

In his conclusion, Tooze draws a parallel between our present aporia and 1914, when an earlier illusion of some “great moderation” was shattered. On this I beg to differ. From where I stand, we are at a 1930 point – soon after the crash, and with a fascist moment upon us. If so, the pressing question is this: when will we rise up against the nationalist international bred across the west by the technostructure’s inane handling of its inevitable crisis?

What seems certain is that the politics of the national state, plus the international bodies, is badly fractured and not fit for purpose for a serious crisis.

Tooze actually wrote a history of the COVID crisis in Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy.

I have not read it, but have heard Tooze interviewed 4 or 5 times. Here is Oliver Bullough in the Guardian.

There are a couple of takeouts from Tooze.

The first is that our unbalanced relation to nature will cause blowbacks.

The second is that financial action taken by conservative governments was not a change in ideology. It was to maintain the current system, where the needs of the financial system, and the wealth it generates for the few, takes precedence over the needs of the many.

The financialisation of the economy in modern times probably dates back to measures taken to fix the Great Depression, as I think Varoufakis suggests.

This and the inequity of political/economic arrangements is fundamental to how we are tackling, or not tackling the climate emergency. Our politics is not fit for purpose, and it shows.

I’ve just corrected the date for the Battle of Leipzig, which was 1813, not 2013. And the link to Stan Grant’s article is now working.

The problem with Grant’s article is that his argument by citation style, while it shows he is a very learned person, sets a lot of ideas running which he does not round up and suggest a solution.

what it did for me was to show that the problem facing First Nations people has to be seen in a broader setting which encompasses the whole human project. Grant did put his finger on something when he cited the French historian Ernest Renan in saying “nations are acts of violence”.

They can be, and the establishment of modern Israel is an example.

There is a sentence or two in passing where he says:

This isn’t about justice. Justice is about rights. It is about recognising the place of First Nations people; it is about restitution.

But that’s not history. History, it seems, is less about rights and more about wrongs.

There are four issues right there – the nature and place of justice, the philosophical/psychological/political concept of recognition, the notion of restitution, which is basically impossible, and whether history is more about wrongs than rights.

Each of these would need a post to deal with. I believe that Grant’s statement just quoted is highly contestable, but I’m sure I don’t have time to deal with it.

So in a way I’ve done what Grant did, throw up a lots of issues.

My overall point is that the problem is as broad as the whole human project, and the political system within which we are addressing these issues is badly broken and not fit for purpose, which is unfortunate when we are facing existential challenges.

Brian: We live in a multicultural country that is mix of various immigrant/religious groups that have settled in Australia. Some of these groups may have stayed as separate groups/religions with a tendency to marry within the group while others while others have spread out into the general population.

Me, I am 3/4 Scottish and, as a child was a right Scottish nationalist.

My wife’s ancestry included people who got a free trip on the second fleet as well as a raft of people from various sources who came from places including, Sweden, England and Ireland. She might be best described as coming from a coal miners subculture. She was most interested in the Swedish connection because she had a Swedish surname.

Our kids think of themselves as Australian with no affiliation with any particular country.

Aborigines have tended not to be included in this multicultural story. Possible reasons include:

Unlike American Indians and Maori the Aborigines didn’t have the organization or weapons to fight wars that were big enough to justify treaties. (Small pox didn’t help either.)

Legal discrimination against Aborigines only ended some time after the 1967 referendum. Illegal discrimination by governments and police lasted longer and we still have a lot of defacto discrimination that disadvantages Aborigines even though the law treats them equally. (Think jailing people for unpaid fines.

There have been no strong Aboriginal organizations that can speak on behalf of Aborigines. (I think it is sad that the Uluru statement was not about creating a strong organization that could speak on behalf of Aborigines.

Many people of Aboriginal descent have merged into the broader society to the extent that their Aboriginality is not much stronger than my children’s Scottishness. (I recall seeing a stat that said about half the people of Aboriginal descent marry people with no Aboriginal descent.

Worth asking how Aborigines might fit into the Australian multicultural system..

John, I’ve been thinking about this on and off, and I think the key is forgiveness.

This can only happen when the First Nations people are shown recognition and those who came later acknowledge the harms that have been done and genuinely seek to make just restitution.

Jacques Derrida wrote a booklet On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness.

Only the unforgivable can be forgiven, and only the victims can decide to forgive.

The Germans invaded 22 countries in WW2, and I think have good relations with all, except perhaps the Greeks but that has nothing to do with WW2.

However, it is not up to the Germans as to whether they are forgiven, it’s a call the victims make or don’t make.

The English were busy killing and dispossessing Scottish people when the English were doing the same thing to Aborigines. (The family claims that one of my ancestors was the only survivor of one of these massacres.) My ancestors were able to get on with it because there were no laws blocking Scottish people from getting on with it.

By contrast, Aborigines were strongly discriminated for and against in Australian law and still are to some extent.