1. Across the ditch

New Zealand has just had a general election. Gareth at Hot Topic tells us that

The National Party has won itself another three years in government. With a probable overall majority and the support of three fringe MPs, prime minister John Key and his cabinet will be able to do more or less what they like. Given the government’s performance on climate matters over the last six years — turning the Emissions Trading Scheme into little more than a corporate welfare handout while senior cabinet ministers flirt with outright climate denial — and with signals that they intend to modify the Resource Management Act to make it easier to drill, mine and pollute, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the next three years are going to see New Zealand’s climate policies slip even further out of touch with what’s really necessary.

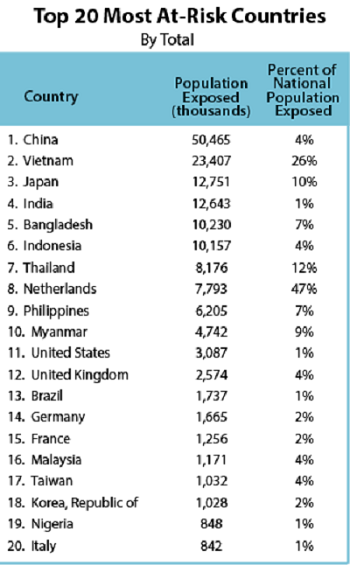

2. China most at risk from sea level rise

An analysis of global vulnerability to sea level rise has been done (see at Climate Central and The Carbon Brief).

China is the standout in terms of people affected, but Japan, India and Indonesia also figure prominently. This may assist international climate action negotiations, though recalcitrants like Canada and Australia don’t figure. Here’s the top 20:

Worldwide they found that “147 to 216 million people live on land that will be below sea level or regular flood levels by the end of the century, assuming emissions of heat-trapping gases continue on their current trend.”

The numbers ultimately depend on the sensitivity of sea level to warming. They say the figures may be two to three times too low, meaning as many as 650 million people may be threatened. Also population increase is not taken into account.

3. Human activities cut animal populations in half since 1970

According to a new report, the Earth has lost half its vertebrate species — mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians — since 1970.

The latest Living Planet Report, put out by a joint research effort between the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London, found a stunning drop of 52 percent in the population of wild animals on the planet over the last 40 years. The most catastrophic drop was among the inhabitants of freshwater ecosystems — the last stop for much of the world’s pollution from road run-off, farming, and emissions — whose numbers declined 75 percent. Oceanic and land species both dropped roughly 40 percent.

It’s also all interconnected; land-use change can affect climate change and animal species both, then the altered climate can in turn affect the animals, and the animals’ effect on their ecosystem can in turn alter the climate again. Animals and humans both are inherent parts of the ecological fabrics they inhabit.

4. The science is clear: act now

Roger Jones and Roger Bodman have an article at The Conversation, republished at Understanding Climate Risk commenting on an article by Steven Koonin, New York University theoretical physicist and former US Under Secretary of Energy for Science, published in the Wall Street Journal and The Australian. Koonin accepts that the climate is changing and that human activity is having an effect, but:

Rather, the crucial, unsettled scientific question for policy is, “How will the climate change over the next century under both natural and human influences?” Answers to that question at the global and regional levels, as well as to equally complex questions of how ecosystems and human activities will be affected, should inform our choices about energy and infrastructure.

Koonin’s argument is technical, but he amplifies the uncertainties and does not properly attend to risk. Details which have no great relevance, such as the failure of models to explain why Antarctic sea ice cover is expanding, are amplified. His conclusion is that the science is urgent, but the uncertainty is such that there is no proper basis for action.

To answer in detail would require a volume. Jones and Bodman address his use of the concepts of doubt, uncertainty, confidence and risk and find his argument lacks an appreciation of how scientists use these concepts. Crucially, “acting now and learning as we go is a better way to manage uncertainty than waiting and learning.” On the main issue,s while uncertainty can be reduced at the margins with observations over time, overall the science is clear, we must act now!

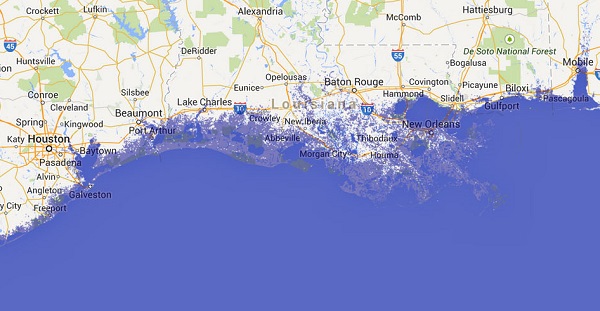

%. No cash flows as Louisiana coast slides into the sea

While the issue is mired in legal wrangles, the Louisiana weltands are sliding into the sea at the rate of 75 square kilometres and saltwater increasingly penetrates. In 2012 a $50 billion repair plane was formulated, but the prospects of adequate funding are remote.

I’ve extracted an image of the flood map showing what 5 metres of sea level rise would look like, which is what I think we are looking at in the next 200 years:

Mind you according to paleoclimate data the long-term effect of 400ppm of CO2 is 25m plus or minus 5. A rise of just one metre badly shreds the coastline.