When I was young, we wore clothes until the wore out. I had an elder brother, and got to wear hand-me-downs.

This all changed, possibly in the 1970s and 1980s. Now we have the phenomenon of single-use clothing, ironically often T-shirts worn by people crusading to save the planet. Richard di Natale is, I think, the Australian politician most often seen in T-shirts. During the last election he often looked like this:

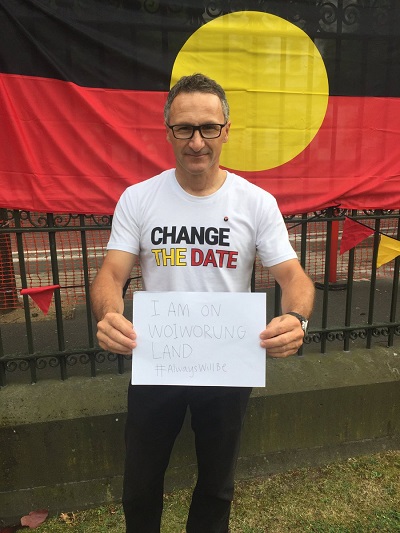

At least he could use that T-shirt more than once, and no doubt from one year to the next, as he could with this one:

He’s even got two to choose from:

I’ll get off Richard’s back now. I researched him because I knew he was given to wearing T-shirts with messages, and one day I’ll explain why I’d like him to wear a 350.org T-shirt, made less likely because their logo is not particularly sexy:

Now The Observer in Britain has done a report Can fashion keep its cool … and help save the planet? which reports that the fashion industry is becoming more conscious of sustainability issues. It’s a bit ironic, however, when the New York fashion season employs single-use clothing to message against ‘fast fashion’:

which will no doubt add to this:

Oxfam reckons Britons would purchase more than 50 million single-use items of clothing during the summer. Apparently 11 million items of clothing end up in UK landfills each week.

- According to a United Nations study, the fashion industry is responsible for about 10% of all greenhouse gas emissions, 20% of all waste water, and consumes more energy than the airline and shipping industries combined.

Vanessa Friedman in The Biggest Fake News in Fashion in The New York Times attacks the myth that the fashion industry is the second biggest polluting industry on the planet. She debunks that myth but accepts that the industry needs to change and comes up with these researched facts:

- Nearly three-fifths of all clothing ends up in incinerators or landfills within a year of being produced.

- More than 8 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions are produced by the apparel and footwear industries.

- And, around 20 to 25 percent of globally produced chemical compounds are utilized in the textile-finishing industry.

Back in 2012 Huffpost ran an article T-Shirt Blues: The Environmental Impact of a T-Shirt, focussing on T-shirts and jeans:

- Each year, over two billion t-shirts are sold worldwide and 520 million pairs of jeans are sold in the U.S. With the production of one t-shirt using up 700 gallons of water and one pair of jeans using up 1,500 gallons, it is easy to understand why the call to curb textile waste is urgent.

Producing a pair of jeans makes as much CO2 as driving 78 miles, a T-shirt 20 miles. While the cotton industry uses 25% of the world’s pesticides and herbicides:

A fading agent called potassium permanganate, starch, and indigo dye waste are often released into the same canals used to irrigate local farms. These chemicals sterilize soil and kill seedlings. According to OnEarth.org, ‘green jeans’ manufacturers may not use pesticides to grow organic cotton, but most organic cotton jeans are treated with conventional chemicals and dyes, which still harm the environment.

Nearly half the life-cycle environmental impact of a pair of jeans comes from washing and ironing. Dry-cleaning a pair of jeans uses the same amount of energy as it takes to heat a home for 387 hours.

At that time the EPA estimated that the average American threw away about 70 pounds of clothes a year.

So greenies who are quick to criticise the cotton industry should give a thought to the environmental impact before they throw on a T-shirt and hit the streets. And people generally should rethink their attitudes to fashion and clothing.

When I was a university student I remember buying three casual shirts on a sale. It was the first time I’d bought clothing for myself, and although I actively disliked two of them after a week or so, they lasted the three years and beyond.

Why only three?

It was the custom back then that you wore a shirt twice before you washed it.

The worst bit was that I was dudded on the sale. I recall them being reduced from 65 shillings to 35. A couple of weeks later the same shirts were in the shop window for 29 and 6.

My habits have changed since then, but when we went to Europe in 2015 I packed much the same clothes as I did in 2008. The photo on the About page dates from 2008. I’ve changed, but I still use the shirt, T-shirt and glasses.

Brian: I just happen to be wearing as I type the last work shirt I got before I left Groote Eylandt over 35 years ago. Never had a set of jeans that went anywhere near dry cleaning.

Problem is my wife won’t let me wear old work clothes to social occasions.

Use Green tee shirts i acquired years ago when working on polling booths. (Liked the slogan. “The future needs your vote today.” Unfortunately the slogan is becoming more and more urgent as the future gets closer and closer.)

John, 35 years is impressive.

I have to admit that as I become more ancient I’ve had to think about how I present myself for work. Some people seem to be a bit uncomfortable about having an old geezer work at their place.

A story I didn’t tell is that we used army stuff after the war. The tunics were particularly useful on cold days.

My mum bought a parachute from army disposals and used it to make sheets, PJs and work shirts.

“Re-purposing” fabrics has become very trendy** amongst the ‘environmentally aware’, even out here in semi-rural Victoria.

I remember the old ‘Army disposal stores’ in the 50s and 60s. Real, actual discarded Army stuff. Amazingly heavy, sturdy wooden boxes; great coats very popular amongst teenagers, etc.

Opp shop clothing racks have long catered for the poor, the hipsters mocking old fashion, and bargain hunters of every social stratum.

But meanwhile many people discard useful clothing and towels etc too soon. Donate it. The unsaleable stuff is used for rags, or dog blankets, or shipped off overseas.

** it’s not enough to rediscover a practice that’s been around forever; you must also invent a fancy name for it