In March this year UN chief Antonio Guterres said he wanted:

- all OECD countries to commit to phasing out coal by 2030, and for non-OECD countries to do so by 2040. Science tells us this is essential to meet the Paris Agreement goals and protect future generations.

He wants the main emitters and coal users to announce their phase-out plans well before the Glasgow UNFCCC COP26 conference in November this year.

In May this year the World Resources Institute (WRI) said of the International Energy Association’s Roadmap to net zero by 2050:

- On the IEA’s pathway to net-zero emissions by 2050, there is no investment in new coal, oil or gas supply. This is a huge step forward for the IEA and an important signal that the world must move away from fossil fuels today — not tomorrow.

In addition to its assumption that we can reach net zero without new coal development, the IEA calls for all unabated coal plants in advanced economies to be phased out by 2030 and in all economies by 2040.

Now a study in Nature by Dan Welsby et al Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world used a global energy systems model to assess the amount of fossil fuels that would need to be left in the ground, regionally and globally, to allow for a 50 per cent probability of limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

See also “Stay in the ground”.

I first saw this in RenewEconomy – 95 per cent of Australia’s coal must remain in ground to meet global climate targets. A better article in terms of the implications for Australia is Cait Kelly at The New Daily – Australia must leave 95 per cent of coal in ground to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, study warns. In addition to coal, she says the study finds:

- A further 35 per cent of Australia’s natural gas and 40 per cent of oil reserves must be kept in the ground, according to the modelling published in Nature this week.

The Morrison government line is always that climate action and a transition to a clean economy will cost jobs and cost the economy. Kelly cites United Nations’ top climate official Selwin Hart who called for Australia to have a “more honest and rational conversation” about urgently abandoning coal:

- “If the world does not rapidly phase out coal, climate change will wreak havoc right across the Australian economy: From agriculture to tourism, and right across the services sector.”

Seriously I don’t know why people argue about this anymore. Do we think we can choose to lose the Great Barrier Reef, have the sea inundate the Torres Strait Islands, plus impinge relentlessly on coastal flatlands, prime real estate and infrastucture in our major cities? Should we look forward to ferocious fires, droughts, storms and floods like never before?

(A recent SMH article showed that Climate damage starting to hit us where it hurts – on the beach in a clear threat to Australia’s way of life!)

In November 2020 Deloitte Access Australia, modelled the choice we face:

- If climate change goes unchecked, then Australia’s economy will be 6% smaller and have 880,000 fewer jobs by 2070. That’s a $3.4 trillion lost opportunity over the next half a century. But there’s a $680 billion dividend that’s ours for the taking if we do rise to this challenge, along with 250,000 more jobs.

However, I was disappointed to read Frank Jotzo and Mark Howden in A promising new dawn is ours for the taking – so let’s stop counting the coal Australia must leave in the ground where they say we should:

- keep our eye on the big picture: diversifying the economy into a broad range of activities with low environmental footprints, underpinned by modern infrastructure, top quality education and a strong social and health system.

Therein lies a desirable and economically sound future for Australia – one where we won’t be worrying one bit about all the coal left in the ground.

I’m sorry, but what the scientists are telling us is that what we do in the next few years, really matters. If we want a chance (albeit only 50 per cent) of a livable future many existing mines and power stations will have to close or become stranded assets, and we do need to be extraordinarily careful in issuing exploration permits.

That is, we need to actively close fossil fuel power as soon as practicable, and adopt a default position of not approving new exploration or fossil fuel developmenmts.

Coincidentally the New Scientist has just published three articles which give us a broader picture:

- Michael le Page – How we can transform our energy system to achieve net-zero emissions

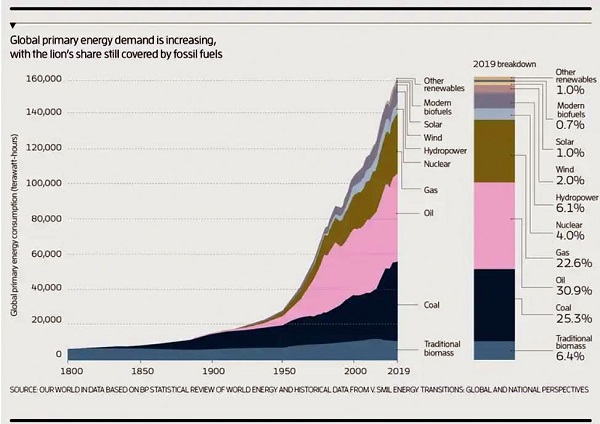

Here is the context of how global energy demand is tracking:

It’s a graph that I used in Five graphs that matter: 2020, and it’s unequivocally bad. If we get lost in the excitement of new renewable energy projects and developments, we need this reality check. The fossil fuel companies continue to plunder the earth.

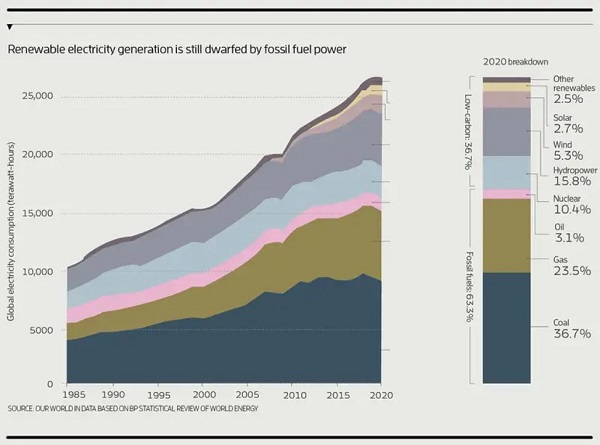

So here’s how electricity generation is going:

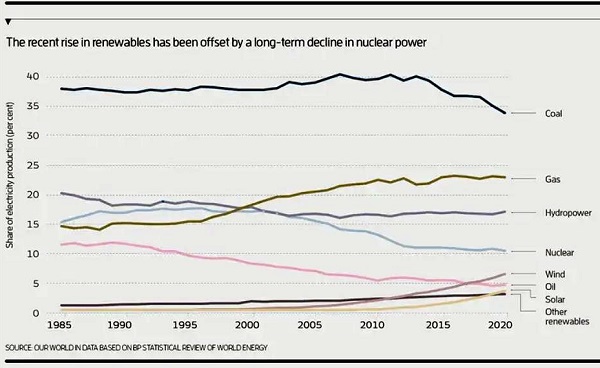

There is less oil on the page, because oil is largely used in transport. Overall we need to graph the power sources separately to see what is going on:

Coal is still by far the largest source of electricity generation. The increase in wind and solar is to a large extent offset by a decline in nuclear. However 75 per cent of new electricity is renewable, but at present this only lifts the proportion of low-carbon electricity from 35.2 per cent in 2000 to 36.7 per cent in 2020.

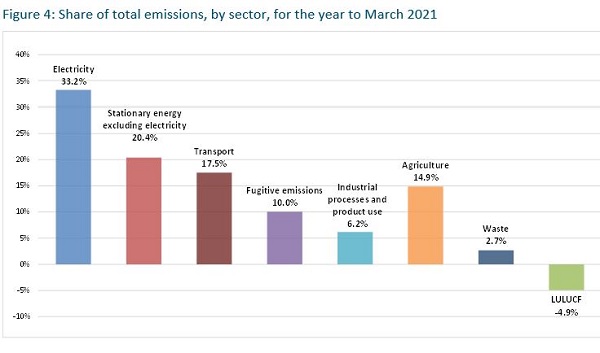

Looking at our Australian situation, this table puts electricity in context in the National Emissions Inventory:

We need to clean up electricity as the low-hanging fruit. That’s 33.2 per cent of our emissions. Then with EVs and such we can clean up transport, which is 17.5 per cent, but that only takes us halfway there.

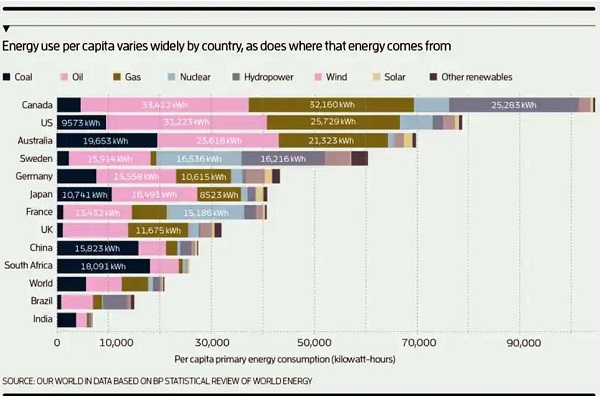

Some say that what we do means little, because we only responsible for 1-2% of emissions. However, we are one of a whole string of countries with similarly small emissions. If we all do nothing the planet is doomed. When we look at our per capita performance, which is a better indicator of our fair share, the New Scientist has this instructive graph:

With the first three bars representing fossil fuel generation, Canada, the US and Australia are in a category of their own, nearly twice the commitment to fossil fuels as Japan, which is next.

In gas and oil, Australia is third, behind Canada and the US. In coal we take the prize, ahead of South Africa and China.

That is just what we burn ourselves, and does not take into account what we sell to others.

Lawton’s article cites Andreas Goldthau at the University of Erfurt in Germany as saying “Coal is finished”, it is just a question of how the transition plays out. Goldthau and colleagues suggest four ways that the transition to clean energy could play out geopolitically. Since the article is no doubt paywalled I’ll give two here:

- 1. Big green deal

A global consensus on the need for the energy transition leads to international agreement and close cooperation between nations. Clear policy signals encourage investors to take their money away from fossil fuels and put it in low-carbon technologies.

Green finance deals help lower-income nations and petrostates with the transitions they need to make. This is the only scenario that hits net zero by 2050, the team concludes.

2. Dirty nationalism

National energy security wins out over tackling climate change. Nations develop inward-looking policies that favour renewable energy sources where they are cheaply available, but also exploit whatever fossil-fuel resources there are. Global markets fragment, breaking the momentum towards a global green energy transition. Efforts to limit global warming to c fail.

The other two, Technology breakthrough and Muddling through, also fail.

‘Dirty nationalism’ represents perfectly the policy of most resource-rich countries, and is evident in PM Scott Morrison’s recent response.

The Climate Council in commenting on the latest IPCC AR6 Report said:

- Based on the latest science, and taking into account Australia’s national circumstances, the Climate Council has concluded that Australia should reduce its emissions by 75% below 2005 levels by 2030, and achieve net zero emissions by 2035.

There is no room for any new fossil fuel developments – including gas – if we’re to avoid catastrophic warming.

Financiers are becoming climate risk averse, as in Australia’s top 5 banks assessing climate risks, regulator says and APRA publishes new details on Climate Vulnerability Assessment (pdf here).

John Quiggin says Yes, it is entirely possible for Australia to phase out thermal coal within a decade, apart from coking coal, but then ‘Green steel’ is [already] hailed as the next big thing in Australian industry.

For me, I wish to point out that the desired scenario Welsby et al are addressing is a 50% chance of stabilising the climate that is already dangerous at a point that is not catastrophic, unless we have already transgressed tipping points. From a risk perspective, this is insane, because a feature of tipping points is that you only know you’ve tipped in retrospect after you’ve tipped. Back in December 2007 James Hansen told 25,000 scientists at the annual American Geophysical Union Conference that for a safe climate we should draw down emissions to reach 350 ppm CO2e in the first instance, and possibly more thereafter.

Since then the delinquency of the international community has been such that every single scenario recommended for a 1.5°C landing now involves overshoot, and drawdown beyond net zero.

What we need now is to treat the climate crisis as a real crisis to avoid catastrophe, not as a walk in the park, making some money as we go.

See also:

Update 14 September 2021:

Two highly relevant articles today.

First, Baseload coal is rapidly losing value, and is biggest risk to Australian utilities.

Marija Petkovic, Founder & Managing Director of Energy Synapse, explains the pricing effects of variable output of wind and solar which have no marginal cost. There is simply no role for coal in a modern electricity system. ‘Baseload’ is an irrelevant concept, because there is none. The business model has changed.

Also:

- The capacity mechanism is simply too uncertain to be relied upon as a saving grace for coal. The transition to clean energy is a threat to traditional energy businesses. But it also presents a once in a lifetime opportunity to reap the rewards from developing a future proof business model that aligns market opportunity with customer and shareholder values. Regardless of the PRRO, the time to plan for coal closures is still now. (Emphasis added)

Meanwhile, Australian and global fossil fuel giants make $1 trillion bet against global climate efforts.

The robber barons are on track to spend $1 trillion on new fossil fuel projects in defiance of global climate change efforts. A new report from Carbon Tracker names names and projects. Included are Australian oil and gas producers Woodside, Santos, Oil Search, as well as companies with a significant Australian presence, including Chevron, Inpex, Shell and Conoco Philips.

Done – 1564 words. I’m still writing to finish discussion rather than start it.

An interesting article I didn’t cite in the post:

South Korea and Japan Will End Overseas Coal Financing. Will China Catch Up?

Since 2013, public finance from China, Japan and South Korea accounted for more than 95% of total foreign financing toward coal-fired power plants in developing countries. South Korea and Japan have now announced they will discontinue this practice. China was by far the biggest provider of overseas coal finance.

Will it follow?

However, coal is losing out in developing countries for three reasons.

Firstly, it is losing its social licence, as in Vietnam, for example.

Secondly, countries are finding that coal is not dispatchable when demand fluctuates.

Third, coal is losing out to renewables on the basis of cost.

I’ve done an update based on two articles that appeared today.

First, Baseload coal is rapidly losing value, and is biggest risk to Australian utilities.

Marija Petkovic, Founder & Managing Director of Energy Synapse, explains the pricing effects of variable output of wind and solar which have no marginal cost. There is simply no role for coal in a modern electricity system. ‘Baseload’ is an irrelevant concept, because there is none. The business model has changed.

Also:

The capacity mechanism is simply too uncertain to be relied upon as a saving grace for coal. The transition to clean energy is a threat to traditional energy businesses. But it also presents a once in a lifetime opportunity to reap the rewards from developing a future proof business model that aligns market opportunity with customer and shareholder values. Regardless of the PRRO, the time to plan for coal closures is still now. (Emphasis added)

Meanwhile, Australian and global fossil fuel giants make $1 trillion bet against global climate efforts.

The robber barons are on track to spend $1 trillion on new fossil fuel projects in defiance of global climate change efforts. A new report from Carbon Tracker names names and projects. Included are Australian oil and gas producers Woodside, Santos, Oil Search, as well as companies with a significant Australian presence, including Chevron, Inpex, Shell and Conoco Philips.

Brian: Methane emissions higher than previous estimates in Queensland’s Surat Basin CSG region

And somebody wants to open up more coal seam gas fields!!!

Yes, John, I saw that and I’m not surprised.

BTW one of our son’s friend’s, a mathematician, works for Shell in monitoring their emissions over the Surat Basin. They know that the emissions will become a factor that will need to be accounted for, so the company is creating its own record.

I don’t know how they are doing it though. The mob who did this study are getting up close to see what is actually happening. I think the official calculation done in the national emissions audit just uses the American figures, which are also not ‘truthed’ by a real check.

China calls for huge boost in coal output at Inner Mongolia mines to fight power crunch

Yes, John, I read an article on my phone about this today. The Chinese seem to be in a real fix, having banned Australian coal, then suffered from flooding and COVID.

Miners have been told they can produce above their quota, and ignore safety considerations.

The article I read went into political ramifications, but I can’t find it now.