1. Melting Antarctica: the time to act is now

In the link above, Graham Readfearn goes into some detail on the likely melting prospects of East Antarctica in particular. The salient points are as follows: Continue reading Climate clippings 139

In the link above, Graham Readfearn goes into some detail on the likely melting prospects of East Antarctica in particular. The salient points are as follows: Continue reading Climate clippings 139

Michael T Klare in an article at Grist claims that Big Oil’s business model is broken.

I’m not so sure. An IEA (International Energy Association) update which he cites is titled A business-as-unusual outlook for oil in the medium term. Certainly there have been changes since the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2014 (see my recent post).

Last September in the Outlook document the IEA saw oil prices rebounding, averaging $82.50 a barrel in 2015 and rising to near $100 in the coming years. Now they see prices recovering gradually to reach $73 a barrel in 2020.

The IEA now sees production as increasing by 5.2 million barrels per day over the same time period, which is substantially the same as forecast last September.

The IEA sees four main factors at play:

North American unconventional production (light tight oil, or LTO) has been greater than expected and has become the top source of incremental supply. Iraq supply increase is also beyond expectations.

Klare’s major point is that the oil industry assumed that demand would continue unabated no matter what the price, leading to massive investment in what he calls “tight oil” – oil from unconventional, hard to get at sources. His thesis is that production and consumption will increase, but only slowly, and to an extent and at a price that will not justify the investment necessary to extract tight oil.

The investment in tight oil dates from 2005, when production was 85.1 million barrels per day. At that time the IEA forecast that demand would reach 103.2 million barrels per day in 2015. In 2014 it was 92.9 with the forecast for 2015 only 93.2.

On the price recovery from $55 per barrel to $73 in 2020, Klare says:

Such figures fall far below what would be needed to justify continued investment in and exploitation of tough-oil options like Canadian tar sands, Arctic oil, and many shale projects. Indeed, the financial press is now full of reports on stalled or cancelled mega-energy projects. Shell, for example, announced in January that it had abandoned plans for a $6.5 billion petrochemical plant in Qatar, citing “the current economic climate prevailing in the energy industry.” At the same time, Chevron shelved its plan to drill in the Arctic waters of the Beaufort Sea, while Norway’s Statoil turned its back on drilling in Greenland.

In that sense Klare is right. Also profits like $32.6 billion in 2013 for Exxon (second only to Apple) and $21.4 billion for Chevron are unlikely to continue. Nevertheless these firms are not out of business. Some of the smaller producers in the sense of firms and countries may be, leading to possible failed states and security concerns. Russia will be producing less.

The bottom line, though, is that the crystal ball is clouded. Uncertainty prevails.

By 2040 three quarters of our energy will still come from fossil fuels, with global energy demand increasing by 37% and emissions increasing by 20%, according to the IEA world energy outlook 2014. IEA Chief Economist Fatih Birol:

The International Energy Agency estimates the planet is on track to warm by 3.6 degrees Celsius. Investment in renewables needs to quadruple to an average of $1.6 trillion every year through 2040 to meet the 2-degree target.

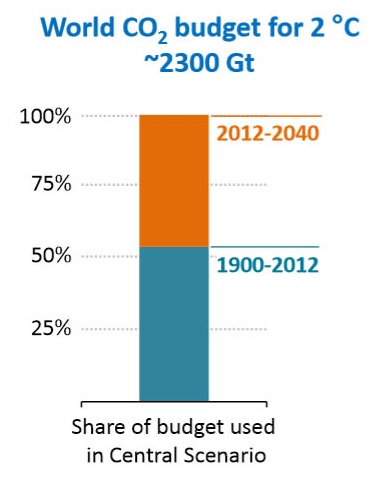

Taking the world’s CO2 budget to limit warming to 2°C as 2,300 Gt of CO2 from 1900, we have 1,000 Gt left from 2014, and are set to use all of it by 2040:

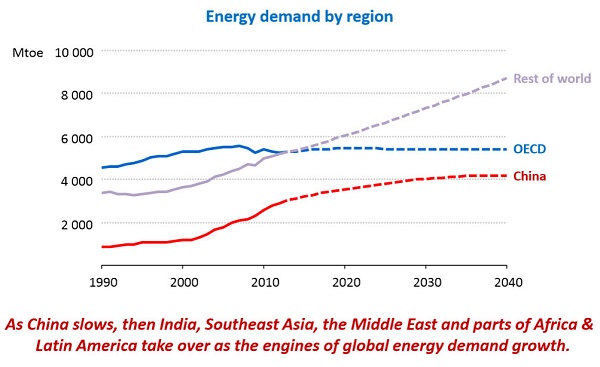

Overall energy demand is set to grow by 1% pa, about half the growth experienced in recent decades. Demand is flat in the OECD, slowing in China, but growing vigorously in the rest of the world:

By 2040, the world’s energy supply mix will divide into four almost-equal parts: oil, gas, coal and low-carbon sources, including renewables, hydro and nuclear. Growth in oil and coal will taper to nothing, but gas will grow vigorously, with demand increasing by 50% by 2040.

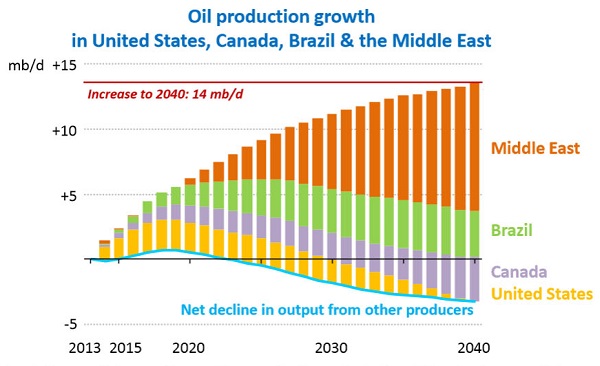

Oil

World oil supply rises to 104 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2040, but hinges critically on investments in the Middle East. As tight oil output in the United States levels off, and non-OPEC supply falls back in the 2020s, the Middle East becomes the major source of supply growth. Growth in world oil demand slows to a near halt by 2040: demand in many of today’s largest consumers either already being in long-term decline by 2040 (the United States, European Union and Japan) or having essentially reached a plateau (China, Russia and Brazil). China overtakes the United States as the largest oil consumer around 2030 but, as its demand growth slows, India emerges as a key driver of growth, as do sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

The changes in supply are shown graphically below:

Concern is expressed that ISIS is deterring investment in production in Iraq.

Oil prices are likely to rebound, averaging $82.50 a barrel in 2015 and rising to near $100 in the coming years.

Coal

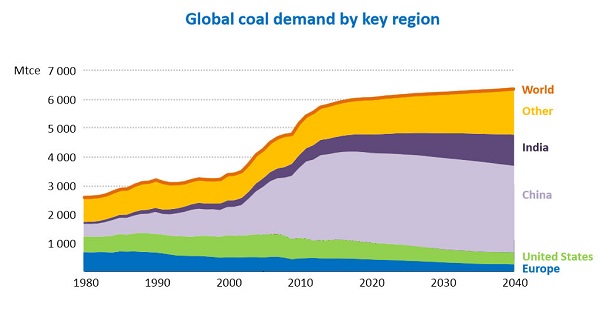

Global coal demand will grow by 15% to 2040, but almost two-thirds of the increase will occur over the next 10 years.

Chinese coal demand plateaus at just over 50% of global consumption, before falling back after 2030. Demand declines in the OECD, including the United States, where coal use for electricity generation plunges by more than one-third. India overtakes the United States as the world’s second-biggest coal consumer before 2020, and soon after surpasses China as the largest importer.

Australia will pass Indonesia to once again become the largest exporter by 2030.

The graph shows the importance of China in the global market:

The graph also highlights the folly of India and developing countries polluting their way to prosperity.

Gas

The key uncertainty – outside North America – is whether gas can be made available at prices that are attractive to consumers while still offering incentives for the necessary large capital-intensive investments in gas supply; this is an issue of domestic regulation in many of the emerging non-OECD markets, notably in India and across the Middle East, as well as a concern in international trade.

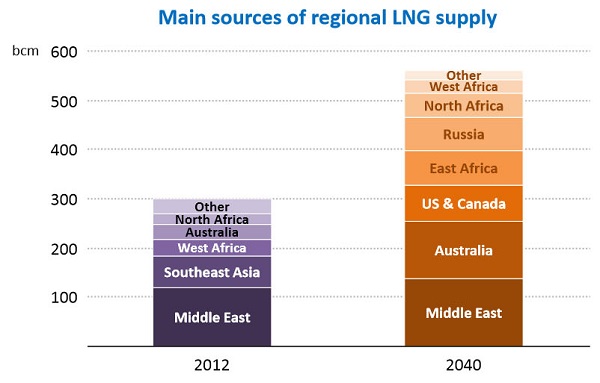

If these uncertainties are met the world gas market will be transformed with Australia a major beneficiary:

60% of gas will be ‘unconventional’, meaning shale and coal seam.

There is uncertainty about the $900 billion per year in upstream oil and gas development needed by the 2030s to meet projected demand.

Nuclear

The IEA sees global nuclear power capacity increasing by almost 60%. However, its share of global electricity generation will rise by just one percentage point to 12%.

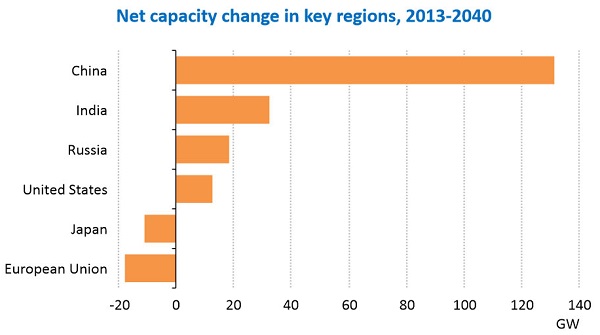

Some 38% of existing capacity will be retired. Once again the importance of China is seen in this graph of the changes in capacity of the key players:

Renewables

Renewables will account for almost half of the increase in total electricity generation to 2040.

The share of renewables in power generation increases most in OECD countries, reaching 37%, and their growth is equivalent to the entire net increase in OECD electricity supply. However, generation from renewables grows more than twice as much in non-OECD countries, led by China, India, Latin America and Africa. Globally, wind power accounts for the largest share of growth in renewables-based generation (34%), followed by hydropower (30%) and solar technologies (18%).

Global subsidies amount to $120 billion compared to $550 billion for fossil fuels.

The growth in hydropower is an ecological concern.

Paris and prices

The Executive Summary leads with a statement about the uncertainty of energy futures in very troubled times, so the IEA forecasts must be seen in this light. The IEA is urging strong intervention by decision makers in the UNFCCC conference in Paris in December, to avoid a climate catastrophe. They call it the last chance. Worth noting here is that the 2011 World Energy Outlook found that all new power supply built after 2017 would need to be zero carbon.

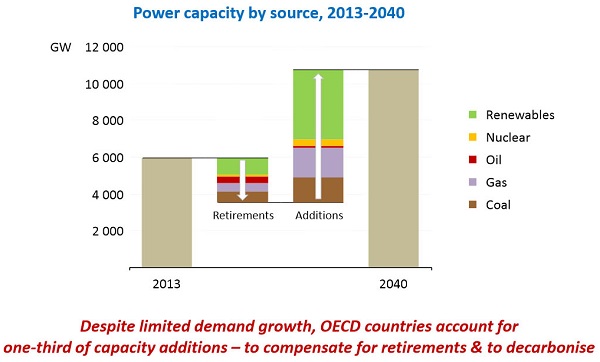

I’m not sure the IEA is fully aware of how cheap renewable technologies are becoming, and how disruptive these technologies will be. Nevertheless their mainstream future, dubbed the “central scenario”, already has renewables comprising about half of new capacity. The changing pattern in power supply is captured as follows:

Clearly we are relying too much on gas and coal for new supply, and we need to retire more dirty power, especially brown coal.

Sources

Unfortunately one can’t read the full report without buying it so I’ve had to make do with links, mostly from this page. The Executive Summary provides the story in words, the pictures all come from the London presentation.

See also Peter Hannam at the SMH, my 2011 post on the 2011 report and Climate clippings 103, Item 4 for a brief treatment of World Energy Investment Outlook 2014.

Also relevant is Mark Diesendorf’s plan for 100% renewable energy in Australia.

BP’s vision

Finally, BP has taken a look at the future. What they find is not dissimilar to the IEA, just heading down the crapper a bit faster. They see global energy consumption in 2035 as 37% greater than now and CO2 emissions 25% more. They see a clear role for themselves to make a buck while cooking the planet.

I like to think that at Climate Plus we cover all the important issues and happenings. In this edition we look at two significant reports, one by Jeffrey Sachs to the UN Secretary General and the IEA’s World Energy Investment Outlook 2014.

As usual use Climate clippings as an open thread on climate change.

1. Deep Decarbonization Pathways

Renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs found that Australia could cut emissions from its energy sector to zero by 2050 and still grow GDP by an average of 2.4% over that period. That was in an interim report recently delivered to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon plotting

specific measures for the world’s 15 largest economies, including China, India and the US, to cut their emissions quickly and deeply enough to meet an international agreed goal of limiting warming to two degrees above pre-industrial levels.

What we do matters!

The report

found that it’s technically possible for Australia to get almost all of its electricity from renewable sources by 2050 and to offset the rest by storing carbon in soil or planting more trees.

We can do that while GDP grows at 2.4% per annum, but it is interesting that our per capita growth rate is the lowest of the 15, India the highest.

There’s more about Sachs here.

2. Catalyst does sea level rise

It was scary, but could have, should have been scarier.

The program depended heavily on the last interglacial, the Eemian, as an analogue for now. It made the link through temperatures and probably got them a bit wrong. We’ll likely get more than 2°C this century, and the Eemian global average was possibly only 1°C higher than now.

Fundamentally the problem is this. CO2 levels during the Eemian which produced around 9 metres of sea level rise were never above 300 ppm. At 400 ppm, as we are now, the implied sea level rise is more like 20 to 25 metres, played out over the centuries.

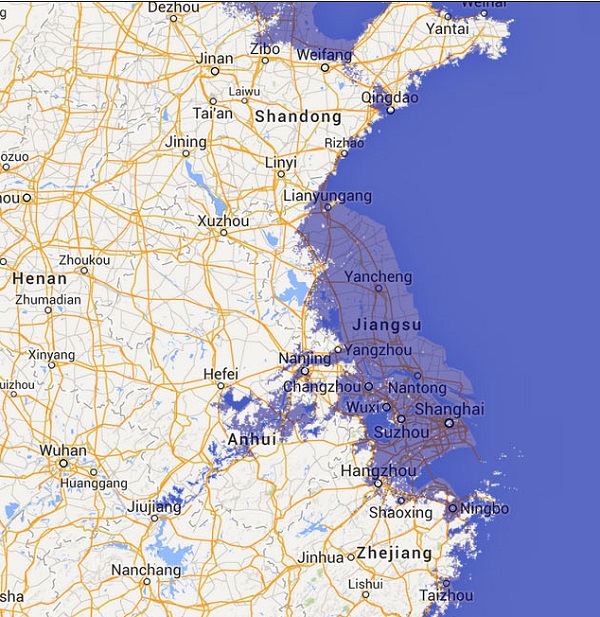

Still they could have pointed out just how horrendous a 9 metre rise would be, other than the throwaway comment about most mega cities being displaced. At 9 metres significant chunks disappear from continents as in China:

Here’s SE Asia courtesy of the Firetree flood map:

At the end it suggested that we could cope by building sea walls, except that it would be expensive. Sea walls are not going to cope with nine metres, let alone 20.

This Skeptical Science post gives useful information about the Eemian, although it too arguably needs updating. I think scientists are settling on a higher sea level rise for the Eemian than the 5 metres suggested, more like the 9 metres of the Catalyst program. Also at least some parts of Greenland are thought to have been 10°C warmer than now, rather than 5°C.

3. The search for the clean coal holy grail

Radio National’s generally excellent Background Briefing program has turned its guns on a ‘clean coal’ technology called DICE – Direct Injection Carbon Engine. Would you believe, a DICE engine runs on a slurry of finely ground coal and water? One purpose seems to be to make brown coal as emissions efficient as black coal – a pointless exercise in terms of current climate mitigation needs. Inherently significant energy must be spent to get the coal into the required state.

The history seems to be one of shonky technology projects run by shonks, but the CSIRO is now involved and our visionary government is throwing money at the venture.

4. World Energy Investment Outlook 2014

The International Energy Association’s latest report is billed as its first full update since the 2003 World Energy Investment Outlook. It’s been out since 3 June. So far I’ve failed in my ambition to do a separate post, so I’ll just do a brief note here.

This post from the Post Carbon Institute is a packet of joy. It says that the IEA report “should send policy makers screaming and running for the exits” or looking for early retirement. Seems we need a mere $48 trillion in investment through to 2035 to keep things on track. But:

The IEA forecasts that only 15 percent of the needed $48 trillion will go to renewable energy. All the rest is required just to patch up our current oil-coal-gas energy system so that it doesn’t run into the ditch for lack of fuel. But how much investment would be required if climate change were to be seriously addressed? Most estimates look only at electricity (that is, they gloss over the pivotal and problematic transportation sector) and ignore the question of energy returned on energy invested. Even when we artificially simplify the problem this way, $7.2 trillion spread out over twenty years simply doesn’t cut it. One researcher estimates that investments will have to ramp up to $1.5 to $2.5 trillion per year. In effect, the IEA is telling us that we don’t have what it takes to sustain our current energy regime, and we’re not likely to invest enough to switch to a different one.

If you look at the trends cited and ignore misleading explicit price forecasts, the IEA’s implicit message is clear: continued oil price stability looks problematic. And with fossil fuel prices high and volatile, governments will likely find it even more difficult to devote increasingly scarce investment capital toward the development of renewable energy capacity. (Emphasis added)