1. Pope Francis becomes active on climate change

Pope Francis is going to give climate change action a red hot go in 2015:

In 2015, the pope will issue a lengthy message on the subject to the world’s 1.2 billion Catholics, give an address to the UN general assembly and call a summit of the world’s main religions.

The reason for such frenetic activity, says Bishop Marcelo Sorondo, chancellor of the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences, is the pope’s wish to directly influence next year’s crucial UN climate meeting in Paris, when countries will try to conclude 20 years of fraught negotiations with a universal commitment to reduce emissions.

He also wants to change the financial system from one based on raw consumerist exploitation to one based on ethics which respect ecological principles. He should have a chat with Naomi Klein!

Giles Parkinson has more at RenewEconomy, including the note that Pope Benedict kicked things off by buying carbon credits in the form of a Hungarian forest to make the Vatican carbon neutral, and the possibility that the Catholic church may divest funds invested in the fossil fuel industry.

2. 2014: the year climate change undeniably arrived

John H. Cushman Jr. at InsideClimate News in reviewing the year thinks 2014 was the year climate change undeniably arrived. It was the hottest year ever, the science became conclusive, and a mushrooming climate movement pressed world leaders to act, which to some extent they did.

On the science, he was referring mainly to the IPCC report where already in 2013 the Physical Science Working Group moved the probability of human causation up a notch from “very likely” (>90%) to “extremely likely” (>95%) which is about as good as it gets. In the Synthesis Report of 2014 the language was ramped up saying that harm from greater warming if we stay on the current course could be “severe, pervasive and irreversible.”

Action looked promising with mitigation pledges by the EU, China and the US, also the UN climate talks at Lima.

On the “mushrooming climate movement he is talking about a:

phenomenon that emerged in a spectacular way in September, on the eve of Ban Ki-moon’s UN summit—the coming of age of a new popular movement demanding climate action now.

Hundreds of thousands of marchers filled the streets of Manhattan, curb to curb for 50 blocks or more. Their presence attested to a new dynamic in which inside-the-beltway lobbyists and well-heeled think tanks joined forces with grassroots anti-fracking and anti-pipeline protestors, in which labor unions and school kids found common cause.

A fine effort, but then, you see, sensible voters stayed at home and allowed the Republicans to take over Congress.

3. Precarious Climate

Climate and political blogger James Wight at Precarious Climate reviews the year, kind of, mostly by listing his best posts.

The last, Australia continues climate obstructionism in Lima, was an excellent wrap of the Lima talks. I was not aware (I’d wondered) that Julie Bishop is a climate denier, along with Andrew Robb, just the pair we needed to represent us at international climate talks.

But not in Australia:

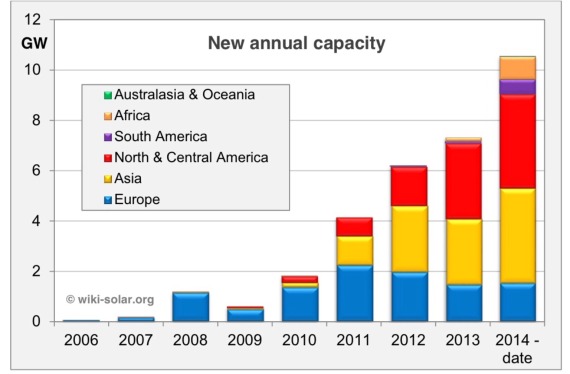

The big surge is in Asia and North America, but other continents have come to life through installations in Chile and South Africa.

5. Production of shale oil increases

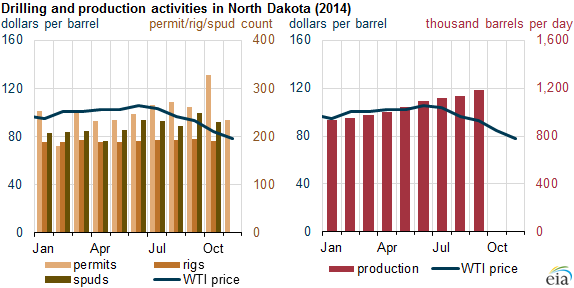

The production of shale oil in North Dakota has increased month by month in 2014, in spite of falling prices.

Meanwhile falling oil prices have hidden a new global warming fee on the purchase of gasoline in California.

6. Compressed air technology

Not everyone reads the discussion threads, so I’m repeating here some links made by Jumpy to compressed-air technology.

Danielle Fong with her company LightSail Energy is bringing compressed-air energy storage technology to the market.

Both Peugot and Citroën are developing compressed-air hybrid cars that use 2 litres per 100 kilometres of fuel. Apart from the hybrid compressed-air powertrain both cars are using light-weight materials and aerodynamics to improve economy. The also have narrow tyres pumped up high.

Of course these cars use twice as much fuel as the electric hybrid Volkswagen XL1 which plans to put 250 cars on the road, at a price. That article is from July 2013 – not sure how they are going.