Several remarkable things happened during the 50-year anniversary celebrations of the “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, Alabama. On that day in 1965 there was a violent confrontation between police and protesters during a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That march is now considered a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement as it led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

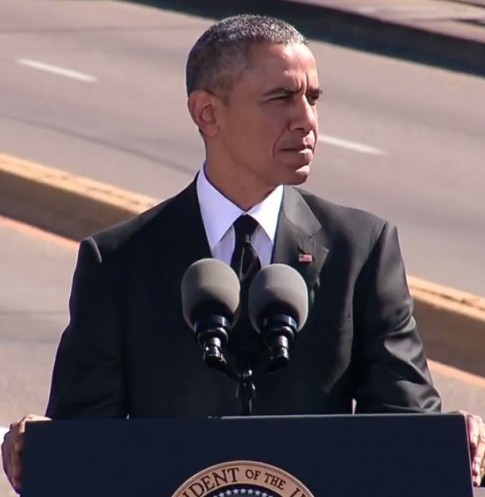

The first remarkable thing was that President Barack Obama crossed the bridge holding the hand of Congressman John Lewis. As Patty Culhane of Aljazeera said:

It is remarkable symbolism. The first African American President walked the span alongside the man who led the march in 1965.

Himself now a Congressman. Progress has definitely been made.

In 2013, however, the Supreme Court weakened, some say gutted, the Voting Rights Act.

The second remarkable thing was that President Obama felt he had to make a call on Congress to renew the Voting Rights Act and to call to account the petty-minded partisans in state governments who see it as their civic duty to pass laws limiting the right to vote. Here is the relevant transcript of Obama’s speech, said to be one of his finest:

With effort, we can roll back poverty and the roadblocks to opportunity. Americans don’t accept a free ride for anyone, nor do we believe in equality of outcomes. But we do expect equal opportunity, and if we really mean it, if we’re willing to sacrifice for it, then we can make sure every child gets an education suitable to this new century, one that expands imaginations and lifts their sights and gives them skills. We can make sure every person willing to work has the dignity of a job, and a fair wage, and a real voice, and sturdier rungs on that ladder into the middle class.

And with effort, we can protect the foundation stone of our democracy for which so many marched across this bridge – and that is the right to vote. Right now, in 2015, fifty years after Selma, there are laws across this country designed to make it harder for people to vote. As we speak, more of such laws are being proposed. Meanwhile, the Voting Rights Act, the culmination of so much blood and sweat and tears, the product of so much sacrifice in the face of wanton violence, stands weakened, its future subject to partisan rancor.

How can that be? The Voting Rights Act was one of the crowning achievements of our democracy, the result of Republican and Democratic effort. President Reagan signed its renewal when he was in office. President Bush signed its renewal when he was in office. One hundred Members of Congress have come here today to honor people who were willing to die for the right it protects. If we want to honor this day, let these hundred go back to Washington, and gather four hundred more, and together, pledge to make it their mission to restore the law this year.

But then he also felt it necessary to call out the voters themselves, who, without discouragement from state laws, do not exercise their vote as much a people in other countries.

Of course, our democracy is not the task of Congress alone, or the courts alone, or the President alone. If every new voter suppression law was struck down today, we’d still have one of the lowest voting rates among free peoples. Fifty years ago, registering to vote here in Selma and much of the South meant guessing the number of jellybeans in a jar or bubbles on a bar of soap. It meant risking your dignity, and sometimes, your life. What is our excuse today for not voting? How do we so casually discard the right for which so many fought? How do we so fully give away our power, our voice, in shaping America’s future?

Fellow marchers, so much has changed in fifty years. We’ve endured war, and fashioned peace. We’ve seen technological wonders that touch every aspect of our lives, and take for granted convenience our parents might scarcely imagine. But what has not changed is the imperative of citizenship, that willingness of a 26 year-old deacon, or a Unitarian minister, or a young mother of five, to decide they loved this country so much that they’d risk everything to realize its promise.

That’s what it means to love America. That’s what it means to believe in America. That’s what it means when we say America is exceptional.

The reference to American exceptionalism is rather ironic (but see below). It is exceptionally dopey to leave voting in the hands of state administrations and not set up a statutory organisation like the Australian Electoral Commission. It is exceptionally dopey too to have the vote on a Tuesday, a working day.

The means states use to discourage minority voting are worth another post, but include ID requirements, challenges to voter registration and the uneven distribution of voting machines, leading to long queues in minority areas. There were even reports of partisans causing traffic jams in areas where minority voters predominate. The difference between black and white levels of voter registration improved after 1965, but are still quite stark.

Voluntary voting requires partisan effort to get out the vote. America is exceptional in that so much partisan effort is also put into preventing people from voting.

The Democracy Now report on the event takes a different perspective. The Selma march was organised because of a police killing of a young black male.

African Americans and their allies attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, demanding the right to vote. As soon as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, they were violently attacked by the Alabama State Police, beaten with nightsticks and electric cattle prods, set upon by police dogs and tear-gassed. They were chased off the bridge, all the way back to Selma’s Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, where the march began. News and images of the extreme and unprovoked police violence, in contrast to the conduct of the 600 marchers, who practiced disciplined nonviolence, spread across the globe. Within months, President Lyndon Johnson would sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act, responding to the public outrage and to the pressure applied by a skillfully organized mass movement.

Edmund Pettus was a former Alabama senator, Confederate general and grand wizard in the Ku Klux Klan.

Three white people “were killed in or near Selma, along with many others, for supporting the struggle for voting rights.” President Obama was referring to them in the second last paragraph of the speech excerpt.

That is special, and once again, the issue of police violence, especially towards racial minorities, is absolutely current.