The USA can no longer be considered a democracy, according to a Princeton University study. Researchers Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page argue that America’s political system is effectively an oligarchy, where wealthy elites wield most power.

Using data drawn from over 1,800 different policy initiatives from 1981 to 2002, the two conclude that rich, well-connected individuals on the political scene now steer the direction of the country, regardless of or even against the will of the majority of voters

They say:

“The central point that emerges from our research is that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy,” they write, “while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence.”

This phenomenon has been a long term trend, at least from 1980, with no difference depending whether Democrats or Republicans were in power. The phenomenon is therefore part of the natural order of things, hard to perceive let alone change.

Ordinary folk also have wins, but only when the elites agree.

Questions raised include why, how do you define ‘elite’ and is the American experience replicated here?

As to why, I can only point to two factors. Firstly, the lobbying industry is alive and well. Big Pharma are said to have more lobbyists on Capitol Hill than there are politicians.

Secondly, I recall in reading about trade matters some 10 years ago that very few Democrat senators were not dependent on business support to finance their campaigns.

In this interview author Martin Gilens identifies the role money plays in the political system and the lack of mass organizations that represent and facilitate the voice of ordinary citizens. Interestingly they found that

policies adopted during presidential election years in particular are more consistent with public preferences than policies adopted in other years of the electoral cycle.

As to defining elites, I would have been interested in the policy preferences of the top one or two percent, who are the real elites in my book. This exchange was enlightening:

Would you say the government is most responsive to income earners at the top 10 percent, the top 1 percent or the top 0.1 percent?

This is a great question and it’s not one we can answer with the data that we used in the study. Because we really don’t have good info about what the top 1 percent or 10 percent want or what issues they’re engaged with. As you can imagine, this is not really a group that’s eager to talk with researchers.

John Davidson drew to my attention this post by Matt Cowgill. Defining the elite by income is no simple matter.

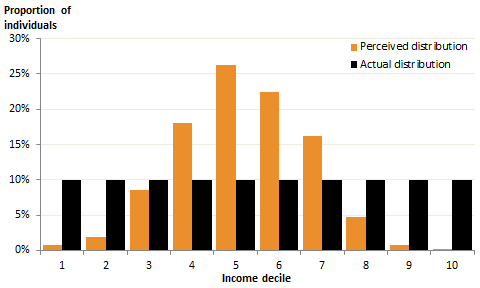

First we have perceptions of income versus reality:

Some 83% of people think they’re in the middle four deciles of the income distribution, whereas by definition only 40% can be. It seems most of us think we are middle class. The rich especially have little idea of how privileged they are.

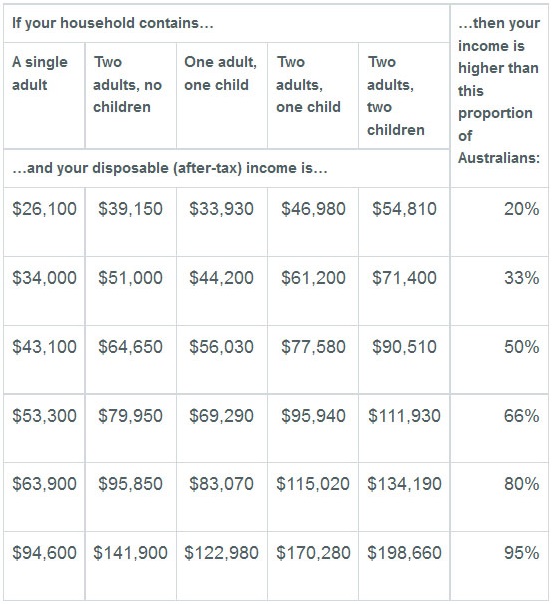

Cowgill leads us through the complexities of analysing wage and income distribution. Of most interest was this table which takes into account household circumstances:

In terms of straight taxable income the top 10% cut in at about $105,000. If we are to do similar research to the Princeton study in Australia, I’d suggest targeting senior executives, I’m guessing in the range of $200,000 plus. They are likely to sit in the top 5% of incomes. They are also likely to reflect the views of the top 2% whose views Gilens found to be unknowable.

If government is to be accountable to the electors, then the Princeton research suggests that universal franchise is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for democracy. We need to think carefully about how democracy works, lest we be left with the form rather than the substance.