On 31 March the IPCC released its second report in the current series, this one on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Follow the links from the report website. We looked at the first report, The Physical Science Basis here, here and here. The third report, Mitigation of Climate Change is now also out, and the final Synthesis Report is scheduled for in September. The series comprises the Fifth Assessment Report.

The IPCC was formed in 1988 and produced assessment reports in 1990, 1995 and 2007. As Graham Readfearn says, the message is the same – we are going to hell in a handbasket – and yes, at that level it’s becoming monotonous.

There is a change, however. It lies in the fact that the impacts of climate change are now all around us. We are not just getting warnings, we are living climate change. The impacts we see locally are integrating into a global pattern, which also includes large-scale transforming events, such as the drying of the Sahel and the loss of sea ice in the Arctic. Increased extreme weather is becoming part of the common experience. In this we are on a path where one in 100 events in any year may become one in three or five. We risk losing whole ecosystems such as the coral reefs where many are in trouble now and all will be by about mid-century, almost certainly. Finally, there is much greater certainty that climate change is happening and about our agency in it. With that certainty comes greater risk, but also opportunity to take action to adapt and to mitigate.

I’ve patterned that paragraph on Greg Picker’s explanation to Steve Austin, while changing the order of the points he made and adding some detail.

The report is organised into two “volumes”, with the first containing 20 chapters, including, for example, one on Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits and one on Human security. These sectoral reports will provide valuable reference material for years to come.

The second volume comprises 10 “regional aspects” including the ocean.

One of the 10 is on Australasia.

Impacts on Australia

Chapter 25 identifies eight significant impacts for Australia:

- There is the possibility of widespread and permanent damage to coral reef systems, particularly the Great Barrier Reef and Ningaloo in Western Australia.

- Some native species could be wiped out.

- There is the chance of more frequent flooding causing damage to key infrastructure.

- In some areas, unprecedented rising sea levels could inundate low-lying areas.

- In other areas, bushfires could result in significant economic losses.

- More frequent heatwaves and temperatures may lead to increased morbidity – especially among the elderly.

- Those same rising temperatures could put constraints on water resources.

- Farmers could face significant drops in agriculture – especially in the Murray-Darling Basin.

University of Queensland marine scientist Ove Hoegh-Guldberg worries that reefs could be severely damaged or disappear by mid-century.

A worst case scenario could see agricultural production reduce by 40% in the Murray-Darling Basin, and in south-east and south-west Australia. The National Irrigators Council says that’s why you have irrigation. However, there is a lot of dry-land farming in these areas and the future average rain is more likely to come in the form of floods when most of the water flows through to the sea.

The above scenarios are risks rather than certainties. However, they add up to a strong chance of dangerous climate change.

Increased certainty

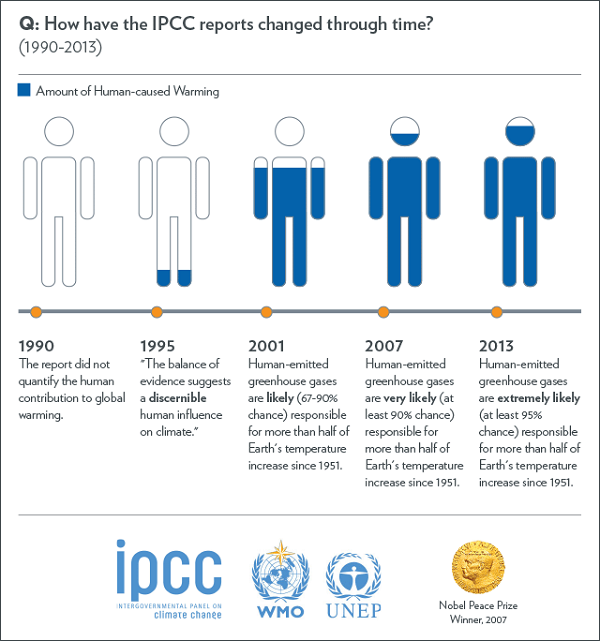

The change in certainty in the attribution of climate change to human activity is conveyed in this image from Dr Jeff Masters’ WunderBlog last year:

Back in 1990 we saw the possibility of continuing change but what we had experienced at that time could easily have been natural variations subject to reversal. In any case there was low confidence that we could do anything to mitigate. Furthermore, why take measures to adapt, when there was no real certainty?

Now the story has changed dramatically. The pattern and the dominant causes are clear.

Adaptation

From page 27 of the Summary for Policymakers we find a graphic packed with information about various aspects of the impacts of climate change (sorry the graphic is too large to display here!) In the right hand column we find bar graphs showing the present, near-term (2030-2040) and the long-term (2080-2100) risk with hatching to show potential for mitigation through adaptation. The long-term risk is displayed in separate 2°C and 4°C bars.

Little adaptation is possible with Australia’s coral reefs, none at 4°C when the risk becomes very high.

Terrestrial ecosystems losing ice cover in the polar regions are similarly not amenable to adaptation and become very high risk at 4°C.

Loss of crop productivity becomes very high risk at 4°C with little possibility of adaptation. Ditto for heat-related mortality in Asia, North America and, presumably, elsewhere.

Burning embers

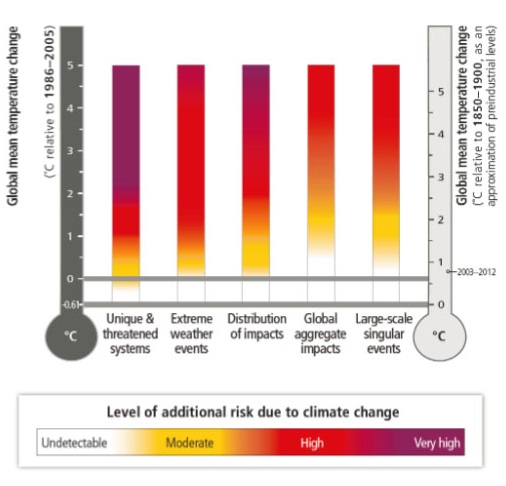

The extensive detail in these tables is summarised in a new improved version of the ‘burning embers’ diagram, shown below:

From this we can readily see that the 2°C ‘guardrail’ marks a fairly arbitrary point on the gradation from dire to downright dangerous.