My dad’s four grandparents all came to Australia as youngsters in the 1840’s. Three were from the Eastern European area of Lower Silesia and the fourth was from Posen Province to the north. While this part of Europe was then part of Prussia, since WWII it has been part of Poland. As far as I am aware, I’m only the second descendent of those four Australian migrants from our branch of the Bahnisch family in Australia to visit the villages where they were born and spent their early lives. The only other person I know of who has done it is Noel Cameron-Baehnisch. He made this journey in 2004 at a time when it would have been much more difficult than it is now!

At the outset, I would like to acknowledge that much of the information that has allowed me to visit these small villages was generously supplied to me by Noel.

Until recently, discussion within our family had centred around the fact that ‘the Bahnisch’s came to Australia from Moettig in Lower Silesia, Prussia’. Nothing much was known in my immediate family about my father’s mother and her parents. So my journey of discovery to visit all four of these villages has been sweet indeed. As you might expect, the first village I visited was Moettig. All of the German place names were replaced with Polish equivalents after WWII, and so Moettig became Motyczyn. So here we go!

1. Motyczyn – formerly Möttig, and home of the Bahnisch’s.

This is a very small village to the N-E of the city of Legnica and about a 1 hr drive west of Wroclaw. In Poland, all villages and towns are announced with a sign of the type shown below. In the right-background can be seen one of the three reasonably new houses in Motyczyn.

A minor road runs through Motyczyn, and the entrance to the south is through an area of (apparently natural) forest (see below). There are two side-roads that constitute the village. On one of these, with only a few houses, I saw small stacks of cut logs. Noel saw a similar scene in 2004, so maybe there is some ongoing income being derived from the forest.

A minor road runs through Motyczyn, and the entrance to the south is through an area of (apparently natural) forest (see below). There are two side-roads that constitute the village. On one of these, with only a few houses, I saw small stacks of cut logs. Noel saw a similar scene in 2004, so maybe there is some ongoing income being derived from the forest.  This is one of the other new houses in town – quite smart, but garden still to come!

This is one of the other new houses in town – quite smart, but garden still to come!  At the corner of the main side-street is a house with a (pink) sign that includes the word ‘Soltys’. Noel says that this means ‘Village Head’.

At the corner of the main side-street is a house with a (pink) sign that includes the word ‘Soltys’. Noel says that this means ‘Village Head’.  Opposite is the house with the best garden that I noticed in the village.

Opposite is the house with the best garden that I noticed in the village.

But apart from a few well presented houses at the far end of the main street (just before it became a track through a wheat field), my overall impression of the village was unfortunately one of despair. Around one-quarter of the houses were no longer inhabited, and were in varying stages of dis-repair/decay.

It’s interesting to think that this large, now derelict and dis-used barn may have had something to do with the Moettig Bahnisch’s!

This is the view of the main side-street from near the far end, looking back towards the road.

This is the view of the main side-street from near the far end, looking back towards the road.  When I arrived back at the ‘main road’ corner, a couple of guys were fixing the front wheel bearings on their old tractor. The younger chap (sitting) spoke quite good English. He said that they have lived here for 12 years and that they have a farm of 12 acres. When I spoke to him about my distant local family connection, unfortunately, he didn’t seem very interested.

When I arrived back at the ‘main road’ corner, a couple of guys were fixing the front wheel bearings on their old tractor. The younger chap (sitting) spoke quite good English. He said that they have lived here for 12 years and that they have a farm of 12 acres. When I spoke to him about my distant local family connection, unfortunately, he didn’t seem very interested.  On the corner of the through-road stood a decorated cross – apparently as an after-math of local Catholic community activities during Lent.

On the corner of the through-road stood a decorated cross – apparently as an after-math of local Catholic community activities during Lent.  As I drove out of town, I observed that even the local crops didn’t seem to be yielding as well as many others I had seen in my travels! But the large woodlot (in the background) seems to be doing well.

As I drove out of town, I observed that even the local crops didn’t seem to be yielding as well as many others I had seen in my travels! But the large woodlot (in the background) seems to be doing well.

2. Dabrowka Wielkopolska, formerly Gross Dammer and home of Franziska Ruciak

Franziska was a Polish lady who married Willi Bahnisch in South Australia. It took me nearly 4 hr to drive the back-roads directly N-E of Wroclaw to reach Franziska’s home town. Dabrowka Wielkopolska is about a 1 hr drive due west of Poznan. I was pleasantly surprised to find quite a large and well-presented town.

While there are at least three roads that lead into the town, this one is interesting. While I was unsure of the meaning of the black silhouette sign in the background, Noel advises that it means ‘Place of Historical Significance’. I noticed these signs often as I approached small villages in the rural areas of Poland. But significantly, I think, there was no such sign on the outskirts of Motyczyn!

As well, behind this sign, you can see an area of wheat. This crop has been planted on several vacant lots witin the town – there are houses all around it!  Often, villages in areas like this in Poland are only a few kilometres apart. As well, they are sometimes connected with walking/bicycle paths as well as roads. At the end of this path, I found a cemetery. I scanned it for the family name Ruciak, but found none. I did, however, find two Franziska’s!

Often, villages in areas like this in Poland are only a few kilometres apart. As well, they are sometimes connected with walking/bicycle paths as well as roads. At the end of this path, I found a cemetery. I scanned it for the family name Ruciak, but found none. I did, however, find two Franziska’s!  This was by far the largest of all of the villages/towns that I visited. While there were some older homes in the town, there were none in the severe state of dis-repair that I had seen in Motyczyn.

This was by far the largest of all of the villages/towns that I visited. While there were some older homes in the town, there were none in the severe state of dis-repair that I had seen in Motyczyn.  And there was a rather wonderful lake in the centre of town.

And there was a rather wonderful lake in the centre of town.  This was a rather stately home, quite close to the centre of town. It seemed to be a private residence, despite the cross on the roof.

This was a rather stately home, quite close to the centre of town. It seemed to be a private residence, despite the cross on the roof.  While there was little commerce to speak of in the town (apart from a couple of small convenience stores), there was an (apparently) new Catholic church with a very modern design. Again, Noel advises that, while this church appears to be new, it is in fact old, but has had recent additions in the ‘folkloric’ style.

While there was little commerce to speak of in the town (apart from a couple of small convenience stores), there was an (apparently) new Catholic church with a very modern design. Again, Noel advises that, while this church appears to be new, it is in fact old, but has had recent additions in the ‘folkloric’ style.  Set behind it was a large old building, clearly with religious significance.

Set behind it was a large old building, clearly with religious significance.  It was locked and didn’t seem to be in use. But, based on its (former) grandeur, it had certainly been a significant building in the community in the past!

It was locked and didn’t seem to be in use. But, based on its (former) grandeur, it had certainly been a significant building in the community in the past! This was the only village in which I didn’t see a cross on a major street corner. Maybe this cross next to the catholic church served the purpose?

This was the only village in which I didn’t see a cross on a major street corner. Maybe this cross next to the catholic church served the purpose?  Another practice in Poland is to place signs at the end of towns leaving motorists (and cyclists and walkers) in no doubt that they are now ‘out of town’!

Another practice in Poland is to place signs at the end of towns leaving motorists (and cyclists and walkers) in no doubt that they are now ‘out of town’!  Being Polish, it would have been expected that the Ruciak’s worshipped as Catholics. But according to Noel, this family was a little different. Apparently, they worshipped as Protestants in the nearby tiny village of Chlastawa. As you can imagine, I was keen to see it. While it was 7 km away by road, in a direct line, the trip to worship for the family would have been a lot less.

Being Polish, it would have been expected that the Ruciak’s worshipped as Catholics. But according to Noel, this family was a little different. Apparently, they worshipped as Protestants in the nearby tiny village of Chlastawa. As you can imagine, I was keen to see it. While it was 7 km away by road, in a direct line, the trip to worship for the family would have been a lot less.

What I found right adjacent to this very small village was a total surprise. There was a massive Ikea distribution (and maybe manufacturing) centre! Along the building frontage, there were 23 semi-trailer loading bays. Nearby, there was a large truck park with dozens of trucks, presumably waiting to be loaded. And there were staff car-parks with hundreds of cars at each end of this massive building.

What I found right adjacent to this very small village was a total surprise. There was a massive Ikea distribution (and maybe manufacturing) centre! Along the building frontage, there were 23 semi-trailer loading bays. Nearby, there was a large truck park with dozens of trucks, presumably waiting to be loaded. And there were staff car-parks with hundreds of cars at each end of this massive building.

What an immense change to the local community/economy this business must have made.

But I was looking for any evidence that there had been a protestant place of worship here in the past. What I found was this Catholic church of wooden construction. And as with all of the other churches I had visited during my travels in Poland, it was locked. When Noel visited Chlastawa in 2004, he was with a Polish guide and was able to gain access to this church. He says that it was originally a Protestant church and dates from before the mid-1800’s. So it is likely to have been the place of worship of the Ruciak family before they migrated to Australia.

3. Pawlowice Wielke, formerly Pohlwitz bei Liegnitz and birth place of Wilhelm August Gregor, father of Louise Gregor, my father’s mother.

Pawlowice Wielke is south of Motyczyn, and only a short drive south-east of Legnica.

This village was a little different from many that I saw in that it had mostly cobbled streets.

This village was a little different from many that I saw in that it had mostly cobbled streets.  There were two very large buildings in the town, one of which had recently had a new roof installed. The second of these buildings was currently having its roof replaced.

There were two very large buildings in the town, one of which had recently had a new roof installed. The second of these buildings was currently having its roof replaced.  For me, the village had a very pleasant atmosphere about it, and it was a satisfying feeling to know that this was where my great grandfather, whom I had previously known nothing about, spent his younger days!

For me, the village had a very pleasant atmosphere about it, and it was a satisfying feeling to know that this was where my great grandfather, whom I had previously known nothing about, spent his younger days!  There were pleasant landscapes and extensive gardens.

There were pleasant landscapes and extensive gardens.  As well, crops in the nearby fields were flourishing.

As well, crops in the nearby fields were flourishing.  As I now expected, I found a decorated cross at one entrance to the village. There was also a stone-fruit orchard nearby with speakers strung in the trees and pleasant music playing. But no people! What was that all about, I wonder?

As I now expected, I found a decorated cross at one entrance to the village. There was also a stone-fruit orchard nearby with speakers strung in the trees and pleasant music playing. But no people! What was that all about, I wonder?  As well, there was a more permanent crypt at another entrance to the village.

As well, there was a more permanent crypt at another entrance to the village.

4. Bielany, formerly Weissenleipe, birth place of Ernestine Pauline Schulz, who married Wilhelm August Gregor and whose daughter, Louise was my father’s mother.

Bielany is a small village quite close to Pawlowice Wielke.

It is a village in two parts. At the bottom end of town by the main road, there are several businesses that you would not normally expect to find ‘in town’, including a scrap metal yard.

It is a village in two parts. At the bottom end of town by the main road, there are several businesses that you would not normally expect to find ‘in town’, including a scrap metal yard.  Again the main street of this small town was cobbled.

Again the main street of this small town was cobbled.  Towards the top end of town, it had an entirely different character …. a pleasant environment with well-tended homes and gardens.

Towards the top end of town, it had an entirely different character …. a pleasant environment with well-tended homes and gardens.

But there was very little still existing in this small town that might give a clue to the child-hood circumstances of my great grandmother.

But there was very little still existing in this small town that might give a clue to the child-hood circumstances of my great grandmother.

Again, at the intersection of the village street with the ‘main’ road was the ever-present cross.

I also attempted to visit the village of Karmin where Franziska Ruciak’s mother was born. I Googled for it and checked with my Navi system and both pointed to the same place, about 1 hr drive north of Wroclaw. So on the way back from Dabrowka Wielkopolska, I set the up the TomTom to go there. The drive across was mainly on very quiet and often one lane roads, with an average speed of about 60 km/hr. Lots of farming and lots of trees – both native and plantation. And it was raining! So this is some of what I saw:

Trees in foreground below are native – in the rear they’re plantation.

Trees in foreground below are native – in the rear they’re plantation.  This is actually a cobbled road!

This is actually a cobbled road!  Finally, I came to where my TomTom said that I had ‘arrived at my destination’! – see below. Not likely! You may be able to see a faint figure in the distance. I hadn’t yet noticed him when I took this photograph. But when I did, he turned out to be a burly, dishevelled looking woodsman. I must say I turned the car around and got out of there very quickly!

Finally, I came to where my TomTom said that I had ‘arrived at my destination’! – see below. Not likely! You may be able to see a faint figure in the distance. I hadn’t yet noticed him when I took this photograph. But when I did, he turned out to be a burly, dishevelled looking woodsman. I must say I turned the car around and got out of there very quickly!

When I returned to my B&B, I found that Noel was indeed correct – there is more than one Karmin in Poland. All I can confirm is that Fran’s mother wasn’t born about an hour’s drive north of Wroclaw!

It has been an emotional experience for me to have the opportunity to travel around these villages. A lot has happened here since the mid-1800’s, so I didn’t expect to see much evidence of the folks who left for Australia. But where are the old cemeteries of the communities who lived here then? Noel advises that most of them were deliberately destroyed after Poland took over in 1945. As well, across Europe, cemeteries are regularly reused by succeeding generations.

There was a lot of destruction in this area during WWII. Maybe that explains some lack of evidence of the past? And of course, there was the forced transmigration of most remaining Germans out of this area into East Germany after the end of WWII. As well, I’m told that Polish people were forced out of their homes to the East of here when part of what had been Poland was incorporated into what are now the independent states of Belarus and Ukraine.

I’m pleased that the folks who left for Australia made the decision to move. Their motivation to move was at least partly economic, seeking opportunity in a new land. It must have been a very difficult decision for them to make. They came to a land with a totally different natural environment and climate that would have seemed very strange to them for a long time! But I’m very pleased and grateful that they made the bold decision to turn their lives upside down for a new life ‘down-under’!

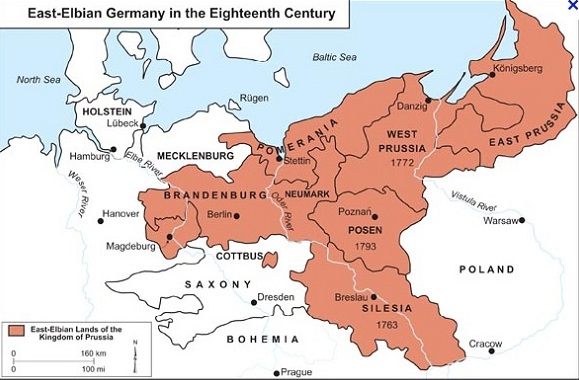

Update (Brian): This map shows the boundaries of Prussia in 1793, which on the eastern side are the same as they were in the mid-19th century:

Möttig, near the city of Liegnitz (now Legnica) is about 70 km west of Breslau (now Wroclaw). Dabrowka Wielkopolska, formerly Gross Dammer, is west of Poznań, pretty much on a direct line between Berlin and Warsaw.

Silesia was ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs under the Bohemian Crown until 1742, when Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia snatched it from Maria Theresa, a 25 year-old woman at the time. In 1740 she had become Queen of Bohemia and in 1745 became Holy Roman Empress Consort and Queen Consort of Germany in an arrangement where she shared the imperial role with her husband in a bandaid solution when the Habsburgs ran out of male heirs. She didn’t give up easily on Silesia, but conceded in 1763 after three wars.

Silesia was about 75% German, but Lower Silesia (western, lower down the Oder River) would have been close to 100%. After WW2 Silesia was assigned to Poland. Some 5-6 million Germans left Poland mostly from Silesia and the provinces along the Baltic (Pomerania, Gdansk (Danzig) East Prussia etc). In the 2011 census only 150,000 of 38 million Polish residents identified as German. Some 60,000 speak a language known as ‘Silesian’, a Slavic language influenced by German. I assume most of them live in Silesia, which now has a population of about 5 million.

Posen became Prussian in the second partition of Poland (by Russia, Austria and Prussia) in 1793. Prussia lost it when Napoleon reorganised the map in 1807 but regained it in 1815. Posen returned to Poland when it was reconstituted as a country after WW1. Silesia at that time remained with Germany.

Posen had about 35% German speakers, mainly in the towns and towards the west.

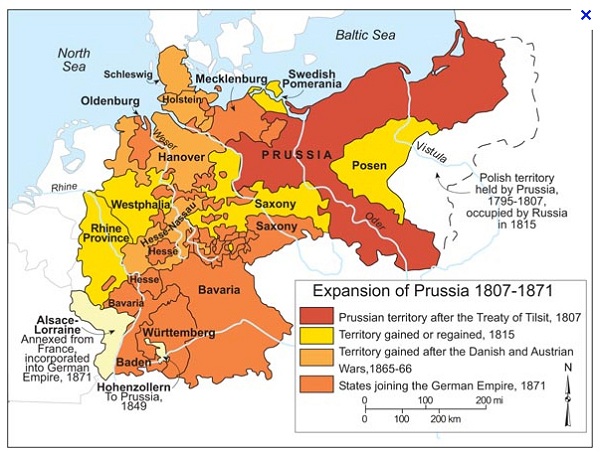

This map shows the changes in Prussia, leading to the reunification of Germany as an empire (there were four kings in that lot) in 1871:

Prussia when our ancestors left Prussia comprised the reddish-brown and yellow parts. Modern Germany is limited to the Oder-Niesse line.