Gareth at Hot Topic has a neat summary of the key points of the IPCC Working Party 3 report: Climate change mitigation report, which I’ve numbered:

-

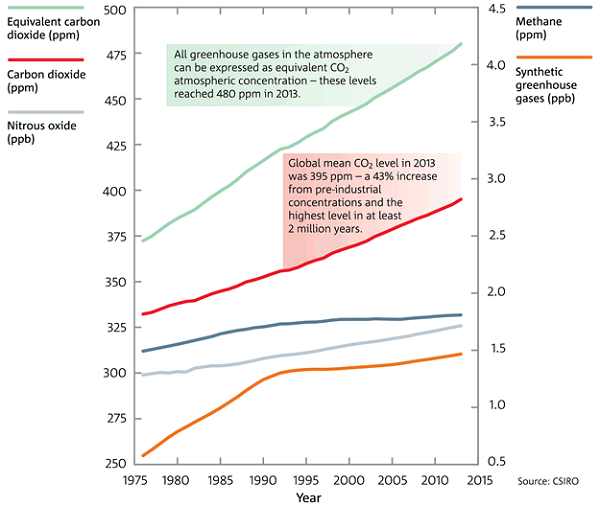

1. Annual greenhouse gas emissions have risen 10 GtCO2eq between 2000 and 2010, and half of all emissions since 1750 have occurred in the last 40 years

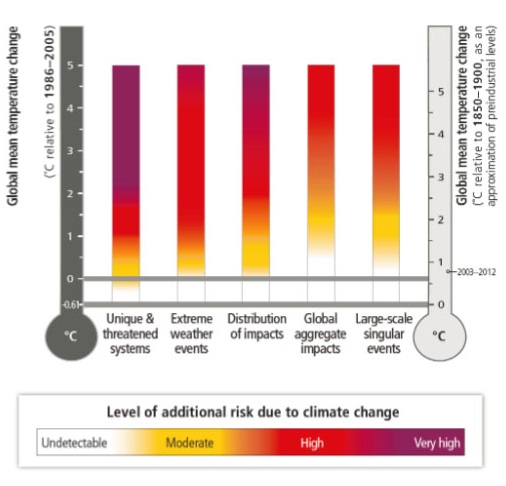

- 2. If no further actions are taken to reduce emissions global mean surface temperature in 2100 will increase by 3.7 to 4.8°C compared to pre‐industrial levels

- 3. To have a reasonable chance of staying under 2ºC of warming in 2100 means restricting greenhouse gases to 450 ppm CO2eq

- 4. Hitting 450 ppm CO2eq will mean “substantial cuts in anthropogenic GHG emissions by mid‐century through large‐scale changes in energy systems and potentially land use”

- 5. Typical 450 ppm CO2eq scenarios include overshooting the target and then removal of CO2 by bionenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), though “carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies and methods are uncertain and CDR technologies and methods are, to varying degrees, associated with challenges and risks”

- 6. The Cancun pledges are not consistent with cost-effective efforts to hit 2ºC, and are more likely to commit the world to 3ºC of warming

- 7. The sooner we act, the cheaper overall mitigation will be – as little as 0.06% of annual GDP growth to hit 450 ppm CO2eq.

The “substantial cuts” in point 4 are in fact 41 to 72% by 2050.

In point 5 the cuts required by 2100 are 78 to 118%. That is, the upper bound requires greenhouse gases to be removed from the atmosphere. This will give a “likely” chance of staying below a 2°C increase in temperature over pre-industrial. In IPCC parlance, likely means a 67% or better chance.

This is not “reasonable” as suggested in point 3, it’s reckless.

I’m surprised at the lack of urgency in the report and the modesty of the targets. A 67% or better chance, considering the risks associated with a 2°C increase, amounts to miserable odds. Moreover, as the CSIRO/BOM State of the Climate 2014 report indicated, we are already at 480 CO2eq ppm:

To make matters worse, the chances of staying under 3°C and 4°C are also only rated in the report as “likely”.

Our current situation demands the ambition and urgency called for by Professor John Wiseman, Deputy Director of the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute at the University of Melbourne:

He concludes that we need more ambition and urgency, both at the national and international levels. The achievement of emission reductions at the necessary scale and speed will require transformational rather than incremental change.

Wiseman goes for a three-phase emissions reduction target regime.

First, a 50% reduction target by 2020.

Second, zero net emissions by 2040.

Third, a carbon draw-down phase to get concentrations below 350 CO2e ppm.

Again, my view:

I applaud his ambition, but, personally, would change the date of the second to 2030 and put a date of 2050 on the third. That is, we should aim for 350 CO2e ppm by 2050.

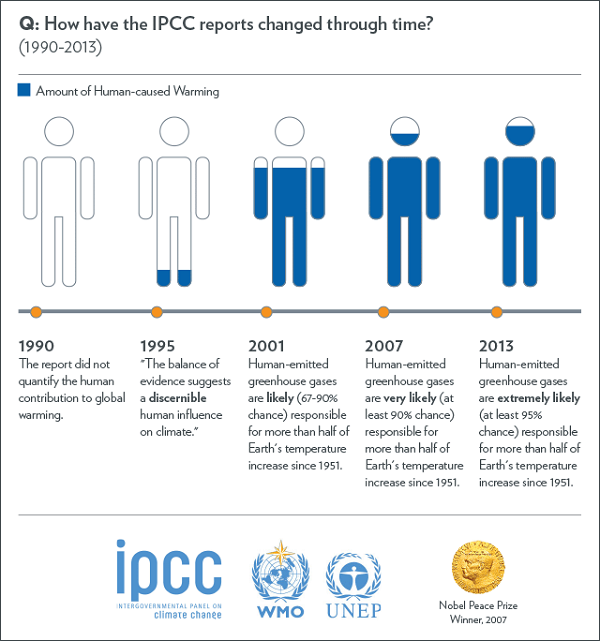

Professor Kevin Anderson of Manchester University and the Tyndall Centre thinks policy makers are in a muddle about the 2°C target. I’m not sure this IPCC mitigation report helps all that much. Furthermore, I think it misleads rather than promoting a safe climate.

The WG1 science report identified the remaining carbon budget we have to work with to stay below 2°C. Rather than elaborate the carbon budget approach, which I described in the second part of this post, the mitigation report lays out a range of scenarios which involve both overshooting and the use of carbon dioxide reduction (CDR) technologies.

In my view policy makers who concentrate on a less than 95% chance of remaining under the 2°C threshold (I’d prefer 1.5°C) should be immediately sacked and replaced by others more fit to purpose. Scientists writing this report have left the real challenge to the politicians, but by normalising scenarios that lack urgency I fear policy makers will descend into a bigger muddle than ever.

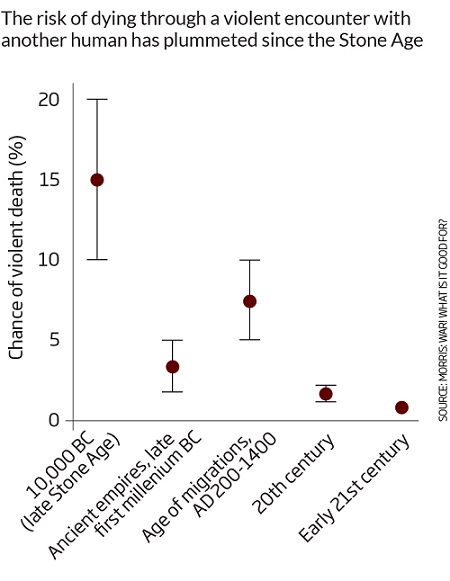

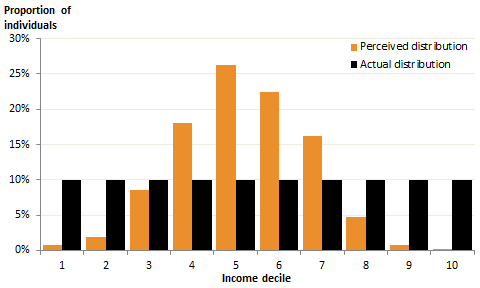

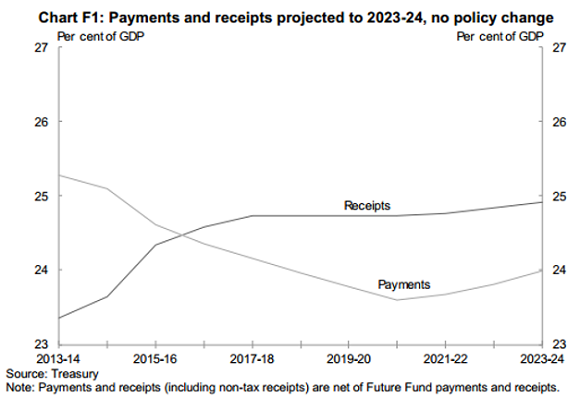

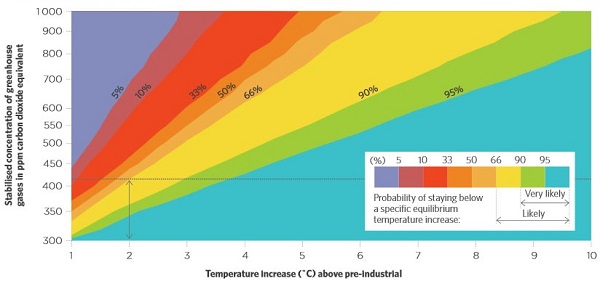

This graph from Malte Meinshausen displayed in the Climate Change Authority report on targets is salutary, considering we are at 480 CO2e ppm:

For a safe climate, the line on the graph should be drawn where 2°C intersects with 95%. That would call for greenhouse gas concentrtions of less than 350 ppm. Back in 2008 David Spratt and Philip Sutton in the book Climate Code Red nominated 320 ppm as the target for a safe climate. They called the 2007 Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC “dangerously conservative”. Not much has changed.

Remember James Hansen nominated 350 ppm not as an end target, rather as an interim goal, whereupon we could decide the next necessary move.

The sad fact is that scientists are not looking at scenarios of 430 ppm or below by 2100. There are too few in existence for the IPCC to summarise.

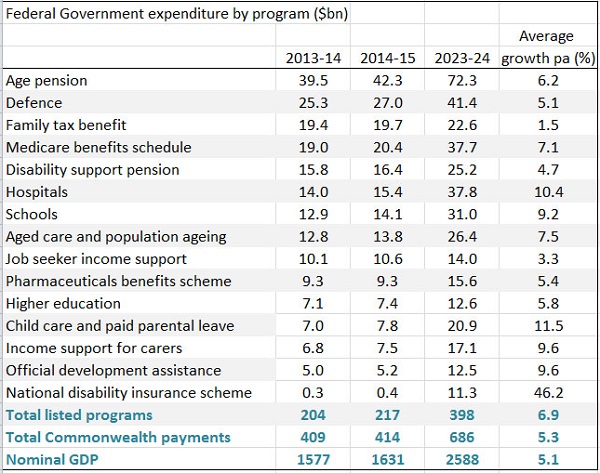

In describing stabilisation pathways the IPCC collated 900 individual scenarios with target CO2 concentrations (for 2100) of 430 to 720 ppm. They then summarised the scenarios in seven categories (see table SPM1 on page 13 of the Summary for Policy Makers). It’s too large to reproduce here.

The first category, the best we are offered, has the following story line.

To achieve CO2e concentrations of 450 ppm (range 430-480) cumulative emissions from 2011 to 2050 must be in the range of 550 to 1300 GtCO2. By 2100 cumulative emissions must be in the range of 630 to 1180 GTCO2. Please note that the upper bound for 2100 is less than for 2050. This will require a reduction of emissions compared to 2011 of 41 to 72% by 2050 and 78 to 118% by 2100. The resulting temperature change will be 1.5 to 1.7 (1.0 to 2.8) relative to pre-industrial. This will give only a 50% plus chance of staying below 1.5°C and a better than 66% chance of staying below 2°C. There is up to a 33% chance that the temperature will go above 3°C and indeed 4°C.

The temperatures in brackets indicate the uncertainties of how the models relate to reality. In fact at section 6.3.2.6 in the main report we are told that the report’s “probabilistic temperature statements should be regarded as indicative.”

The second category uses a target of 500 ppm (480-530), which only yields a “more likely than not” chance of staying below 2°C, that is >50%. Each category summarises a proportion of the 900 scenarios modelled. Each individual scenario is different depending on whether cuts in emissions are made early or late.

From there it obviously gets worse.

Scientists may be dealing with expected reality, but they have left the real challenge of dealing with the climate to the politicians. Moreover, the action required for a safe climate, as outlined by Wiseman, lies outside the frame of the stabilisation pathways outlined in this report. Approaches such as the International Energy Association’s (IEA) World energy Outlook 2011 highlighting an energy crunch for fossil fuel power generation by 2017 probably has more effect.

Key posts

These are the key earlier posts linked above:

Additional reading

Here I’d highlight the article at The Conversation by David Stern on concerns that the IPCC report was censored. This is a misunderstanding of the process. The main report includes a Technical Summary which is prepared by scientists. The Summary for Policy Makers is about a third the length and results from a political filter applied at the end. The material left out, according to Stern, relates to sensitivities and bargaining positions in the current round of UNFCCC talks aimed at striking an international agreement in December 2015 in Paris.

There’s more on the report at Climate Institute, at at Climate Central, at The New Scientist here and here, and at the BBC.

Carbon Brief went wild, producing a dozen posts which I’ve listed here for the record. I’d recommend the first two by Robin Webster for a quick overview, but Ros Donald on fracking and Mat Hope on acronyms may be of particular interest.

13/4 What’s mitigation? A short and straightforward summary of the IPCC’s latest report Carbon Brief staff

13/4 Not just another climate report: main messages from the UN report on tackling emissions Robin Webster

13/4 The what, when and where of global greenhouse gas emissions: A visual summary of the IPCC’s climate mitigation report Mat Hope

13/4 From RCP to WG3: A climate change acronym cheat sheet Mat Hope

14/4 Does the IPCC endorse fracking? Ros Donald

14/4 Climate fixes and Plan Bs: The IPCC’s guide to staying below two degrees of global warming Roz Pidcock

14/4 Media reaction: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s big climate mitigation report Ros Donald

14/4

Daily Briefing | IPCC: There’s still time to take climate action, if countries cooperate Carbon Brief staff

15/5 Degrees of change: the IPCC’s projections for future temperature rise Robin Webster

16/4 Tackling global warming could slow global growth – by 0.06 per cent, IPCC predicts Mat Hope

17/4 IPCC review of farming and forests leaves key questions about effect on climate change “unresolved” Robin Webster

17/4 Climate change is a political animal Paul Tobin

Independent Australia also looks at fracking and gas.

Developing countries are unhappy.

Please contribute other useful links in comments.